Who would become a local politician?

We have to put power back into local politics. This puts power back into the act of voting. That would be good for all of us writes Colette Finn, Deputy Lord Mayor of Cork.

My politicisation began in Africa in the 1980s, when I went to work on the Medical Laboratory Training Project. I observed an economy based on subsistence farming and repatriated monies sent by migrants. This experience in Africa taught me that the who, what and why of decision-making matters.

Politics really matters. Women can be told that politics is best left to the men.

This is untrue; gender also matters. In 2010, I was one of the founders of the 50/50 group in Cork. The group was set up to raise awareness amongst the public about the underrepresentation of women in politics and why it mattered. We also aimed to put pressure on the Government to live up to its commitments on gender equality.

In 1985, the then Taoiseach, Garret FitzGerald, signed the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). This committed Ireland to addressing the gender imbalance in Irish politics. Candidate gender quotas are a mechanism that can help address this imbalance. Ireland enacted candidate gender quota legislation in 2012. This legislation tied public funding to candidate gender balance in general elections. It forced the political parties to pay attention to the gender issue.

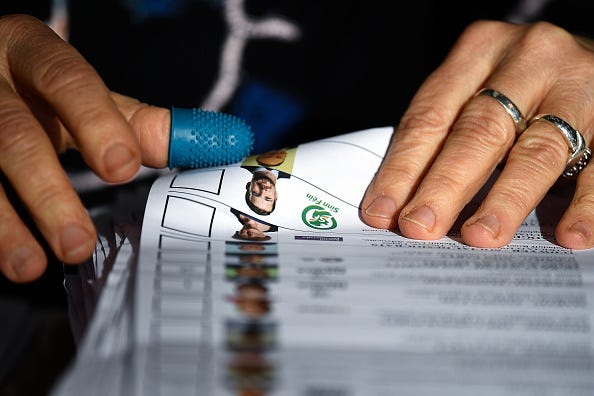

‘Why would you want to be a councillor?’ Invariably that is the reaction that I encounter when I tell people that I am an elected councillor. There is usually a look of pity or derision on people’s faces. This is not good in a democracy. Having first come into effect in the 2016 general election, gender-balanced representation is an important issue for our political parties.

Having stood as a candidate for the Green Party in 2019, I was honoured to be elected. However, I did not doubt the challenge of taking on a job where there are lots of different expectations. That is the substance of this article. What does the public really want their councillors to do? What does the political system really want its local councils to do?

The Moorhead report on the role and remuneration of Local Authority elected members1 concluded that the role of councillor should entail five main areas of work:

Policy making and local authority performance in the delivery of its services

Oversight, governance and compliance of and by the local authority

Representing the local authority and the community on external bodies

Community leadership and political advocacy

Representation of individual constituents, as appropriate.

Sara Moorhead SC, the report’s author, argued that councillors spend too much time on the public-facing aspects of the job. She contended that they should limit their interactions with the public and maintain their council membership as a part-time role.

Consider the important roles of our local government. These encompass planning, enterprise and economic development, social and community development, climate action, housing, infrastructure, transport, libraries, recreation, and culture. The total number of services provided by local authorities in Ireland is more than 1,100, ‘ranging from abandoned vehicle removal to Zoonose monitoring’ (the tracking of diseases transmitted from animals to humans)

Think how much influence all these areas of responsibility have over the lives of our citizens. Nonetheless, Ireland’s local government system has been described as the Cinderella of the political system, a system that is relatively weak in terms of powers and responsibilities.

For example, on average, Ireland has one council per 160,000 citizens, contrasting starkly with France where the ratio is one council per 1,600 citizens, or Germany where there is one council for 5,000 citizens. Ireland is typically ranked at, or near the bottom of, the international Local Autonomy Index, which ranks local government systems in terms of their autonomy.

At present, there are 31 local authorities, down from 114 in 2014. The number of elected councillors per head of population has fallen from 1:1,600 in 2014 to 1:4,830 today. It is also underfunded. In 2008, there were 38,000 local authority staff in Ireland, while in 2022 there were just under 32,000, nearly 6,000 of whom are in Dublin City (2022).

Local government spending as a percentage of total governmental spending is typically around 8 per cent in Ireland, with the EU average at 23 per cent, and in Denmark it is 64 per cent. Our local government has been starved of resources.

Local authorities have no particular powers to introduce their own levies, such as a bed tax on hotels, or an upperstorey vacant unit charge that is different from a vacant site levy. Those are the kind of levies that could support urban regeneration and increase residential living in the city, but the local authorities at present do not have adequate scope for autonomous, proactive, pro-social decision-making.

In Ireland, we have laboured under the defunding of public administration; public services have been outsourced to the community and voluntary sector rather than directly delivered by local councils. This further erodes public confidence in public administration and politics.

One of the good things that came out of the banking crisis is that it undermined – fatally, I hope – the idea that the profit motive would deliver for the public good. Privatisation is not and never will be a solution to public sector reform.

We have to put power back into local politics. This puts power back into the act of voting. That would be good for all of us.

Social media pressure and the rise of the far right have added to the demands of the job. Social media is a new phenomenon. Abuse that was always there is now amplified and made more invasive because it can come through your phone. However, politics is a workplace and, as such, the standards that apply in any workplace should also apply to politics.

Colette Finn is a Green Party Councillor and Deputy Lord Mayor. A former researcher at University College, Cork, she spent more than 30 years in the Hospital Laboratory Service and has studied Economics to doctoral level.

This article originally appeared in the Winter Edition of the Local Authority Times.

How can we strengthen local government in Ireland?

Cinderella and the Constitution I cannot claim credit for coining the phrase that local government is the Cinderella of the Irish political system. It has been used by other academic scholars before and what they generally mean is that local government is under-studied, under-researc…

Great article. As much as the general public is against paying huge salaries to elected politicians, local representatives in councils are not paid enough while their workload is significant, so they tend to have a second job just to make ends meet.

On top of it all, expectations from local communities are often unrealistic, in part because the average person does not know enough about how decisions that might affect a local council are made.