How can we strengthen local government in Ireland?

With more councillors, more autonomy and far bigger budgets. Maybe then we’ll be ready for directly elected mayors in Cork writes Dr. Aodh Quinlivan

Cinderella and the Constitution

I cannot claim credit for coining the phrase that local government is the Cinderella of the Irish political system. It has been used by other academic scholars before and what they generally mean is that local government is under-studied, under-researched, under-analysed and under-valued. I think all of this is true, but there is also an optimistic element to the story in terms of Cinderella being lifted from obscurity to a position of honour and significance. Perhaps local government in Ireland will one day occupy a position of prominence in this country?

Structurally, our model of local government is straightforward. We have a single-tier system with 31 local authorities. There are three City Councils in Dublin, Cork and Galway. There are combined City and County Councils in Waterford and Limerick – in other words, the City and County Council have merged.

Then we have 26 County Councils, three of which are in Dublin. We are unusual in Europe in not having a lower tier of local government at the town level. In 2014 we abolished our Town Councils. Comparatively speaking we have very little local government, very few councils and very few councillors – since the end of the 19th century we have reduced from over 600 councils, down to 114 and now down to 31.

With the abolition of Town Councils in 2014 the number of councillors fell from 1,627 to 949. Our ratios in terms of councils to citizens and councillors to citizens are large and you can argue that the system is becoming less and less local.

Another aspect where we differ from the norm is that local government – though recognised in our Constitution – is not protected in our Constitution. The Council of Europe has slammed Ireland for its lack of constitutional protection for sub-national government and claims that it is indicative of a fundamental lack of respect for local government.

So, for example, in 2013, it was not possible to abolish Seanad Éireann without a referendum of the people because it is protected in the Constitution; yet a year later, a whole tier of local democracy and 80 directly-elected councils were abolished with no reference to the people. I refer back to Cinderella and neglect!

Subsidiarity

In July, the Council of Europe’s Congress of Local and Regional Authorities (CLRAE) produced a draft report on local democracy in Ireland, in particular the extent to which we are honouring our commitments to the European Charter of Local Self-Government.

The principle of subsidiarity is the major one contained in the charter – this requires that public responsibilities should be exercised by those authorities which are closest to the citizens, and that local authorities should manage a substantial share of public affairs under their own responsibility.

CLRAE expressed concerns about many aspects of our local democracy, starting predictably with the fact that we are ‘far from complying with the principle of subsidiarity’ and that central government retains control over many functions which could be devolved locally.

Depressingly the draft report noted: ‘There are no signs that central government supervision is about to be relaxed’ and ‘the range of responsibilities handled under local self-government is clearly fewer that in most European countries.’

Is bigger really better?

As in their previous 2001 and 2013 reports, the system of local authority financing was strongly criticised due to the limited range of own resources which councils can use. In this regard, the conclusion was that we do not meet the charter’s requirement of adequacy. Local government spending as a percentage of total governmental spending is typically around 8% in Ireland; the EU average is 23% and, in Denmark, it is 64%.

The dead-hand of centralisation is suffocating the life out of local government – functional centralisation, financial centralisation and administrative centralisation whereby so many pieces of paper have to be signed off in Dublin for local decisions.

Successive governments have blindly followed an appealing but fundamentally incorrect narrative which is: BIG IS BETTER; BIG IS CHEAPER; BIG MEANS IMPROVED SERVICES; BIG IS MORE EFFICIENT. And yet, the international research evidence refutes this narrative. The evidence informs us that a smaller number of larger local authorities do not yield improvements, savings, and efficiencies. To paraphrase Professor Howard Elcock, the amalgamation and abolition of local authorities is an addiction suffered by central governments.

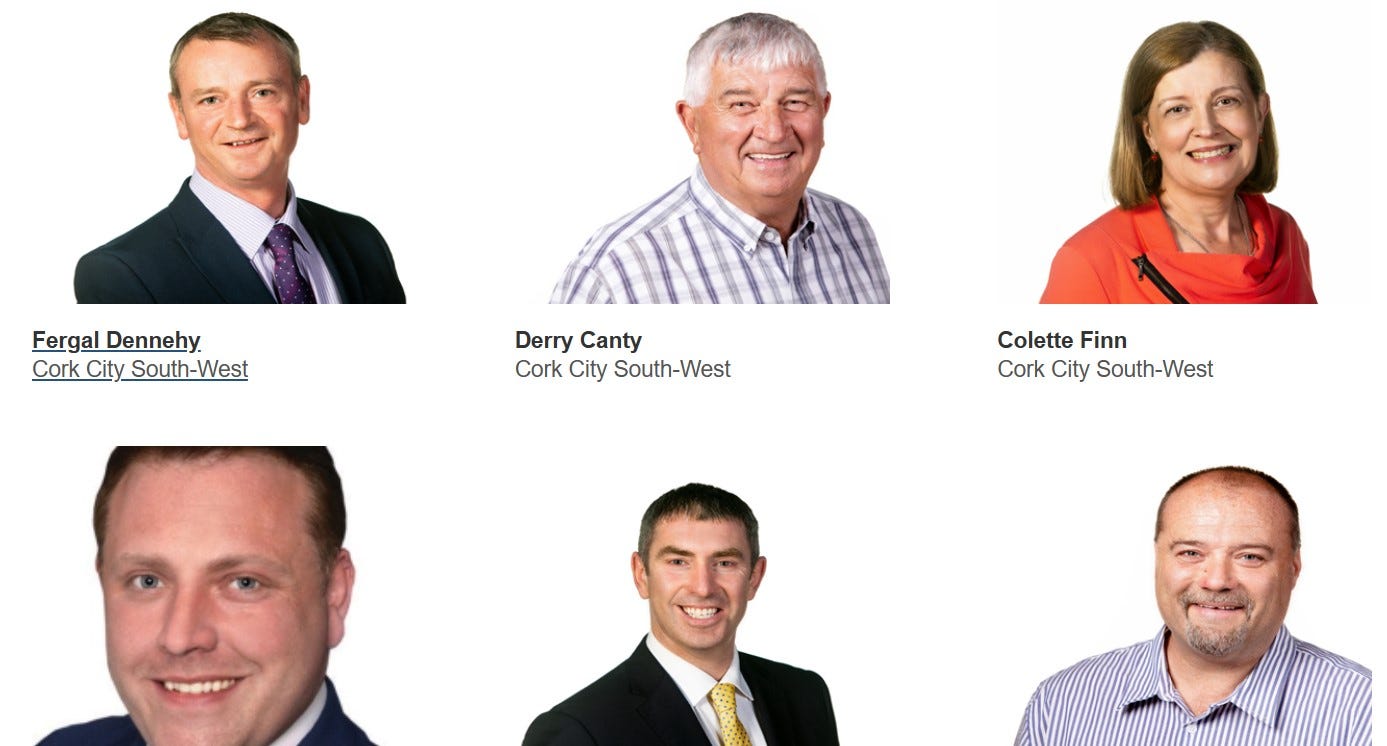

The knock-on effects are serious. The council elected in May 2019 in Cork city had a ratio of one councillor per 6,800 citizens. This is a massive number in comparison to 1:120 in France, 1:210 in Austria and 1:350 in Germany. This is leading to a political fallout and we have seen many councillors quit over the past few years, citing the fact that their jurisdictions are too large and require them to be full-time councillors. Yet, they are not being rewarded with a full-time salary and find it next-to-impossible to balance their council role with their day-to-day working lives and family commitments.

The reform agenda of the current government – such as it is – has the introduction of directly elected mayors as the headline act. Here’s the thing though. Direct mayoral models only tend to work in countries with strong local government systems. In Ireland, directly elected mayors will work if they are embedded into a wider set of reforms. In other words, grafting a directly elected mayor onto the current system, without any meaningful changes to local government responsibilities and financing, may not make any appreciable difference.

Legislation was passed in 2001 under Minister Noel Dempsey, to introduce directly elected mayors, for a five-year term, with executive powers from the 2004 local elections. Two years later, in a dramatic shifting of position, the government repealed the directly elected mayor proposal. The matter was put on hold until 2007 when a coalition government was formed with Fianna Fáil, the Green Party and the Progressive Democrats. That government pledged to introduce a directly elected mayor for Dublin with executive powers by 2011.

In April 2008, Minister John Gormley published a Green Paper, which contained a useful and well-framed discussion of the directly elected mayor issue. Alas, by the time the government left office nearly three years later, no White Paper had been produced and none of Minister Gormley’s reform ideas had seen the legislative light of day.

It was a further three years before the issue of directly elected mayors came forward again in legislation, this time under Minister Phil Hogan’s Local Government Reform Act, 2014. The legislation proposed the holding of a Dublin plebiscite on the issue on the same day as the 2014 local elections. However, the legislation included a provision that each of the four local authorities which constitute the Dublin Metropolitan Area would firstly have to individually adopt a resolution in favour of holding the plebiscite. Three of the four Dublin local authorities comfortably adopted resolutions in favour of the plebiscite, but Fingal County Council, as it was fully entitled to do, did not and that was the end of it.

Try something

That is, until 2019 when it was announced that there would be local votes or plebiscites on the matter in Cork city, Limerick and Waterford, with Dublin to get a Citizens’ Assembly as an initial step. Limerick said ‘yes’ by 52.4% to 47.6% while Cork and Waterford narrowly said ‘no’. After an unnecessarily lengthy delay, the historic Limerick mayoral election will take place in 2024; meanwhile, on foot of the report by the Dublin Citizens’ Assembly, there will be a plebiscite on the matter in the capital.

The current Programme for Government states in black and white that plebiscites will be held in 2024 in any local authority that wishes to have a directly elected mayor (at the request of the council or a petition signed by 20% of voters). There are no indications that any local authority is interested in availing of this offer.

In the meantime, all eyes turn to Limerick. Will a directly elected mayor in Limerick be a game-changer and a catalyst for wider local government reform? I do not know and it is difficult to be optimistic given the history of local government in Ireland.

I quite like Chaos Theory and the idea of disrupting the status quo. The Butterfly Effect indicates that a small change in one component can result in significant differences in other dimensions. It is time to disturb the system and shake it up. Anthony Burgess once wrote the following:

‘It is common sense to take a method and try it; if it fails, admit it frankly and try another. But, above all, TRY SOMETHING.’

After more than 20 years talking about directly elected mayors, now is the moment to try something.

Dr. Aodh Quinlivan is the Director of UCC’s Centre for Local and Regional Governance. He is the author of nine books on different aspects of local government, including the forthcoming First Citizen: Seán French, Cork’s Longest-Serving Lord Mayor (co-written with John Ger O’Riordan). You can follow Aodh on Twitter/X.

Tripe + Drisheen welcomes a range of voices to write on all aspects of life in Cork. If you’d like to a write a guest essay, drop us a line at tripeanddrisheen@substack.com with the subject line “Guest Essay” and a brief outline of your topic.

From the archive:

"Above all this is a vote about fairness”

The upcoming vote by Cork City Council regarding Bishop Lucey Park is a marker for how seriously this city takes the era-defining, existential threats of climate change and biodiversity loss but, above all, it’s about fairness. We may…

Great article as always. Loving the amount of output recently.