It’s a quarter century since Cónal Creedon’s first collection of short stories, Pancho and Lefty Ride Out, was published. Hear Cónal talk about Pancho and Lefty Ride Again by clicking play above.

Taxi for Finbarr Creedon

“Oh, she was a great dog. She was called Finbarr. She had a job in RTÉ and everything.”

Cónal Creedon’s eyes light up. Is it mirth, or mischief, or the sheer love of telling a good yarn? Hard to say.

At the end of our interview, I ask him about a series of photos of him that did the rounds when he was first establishing himself as a writer: Creedon seated in an armchair out on an abandoned Coburg Street, near his former shopfront, with a small Corgi-like dog in his arms.

This, apparently, was Finbarr Creedon, and she was the source of a small dispute in RTÉ Cork.

“She used go in to do the links for The Swamp, the kids show they were making at the time,” Creedon tells me. “But they’d want her to arrive clean, so they’d send a taxi over to the shop, and the taxi driver would come in and say, ‘Taxi for Finbarr Creedon!’ And off she’d go. They’d walk her back afterwards.”

Eventually, as he tells it, the dog’s curiously human name appearing on the weekly expenses tab drew the attention of he-who-held-the-purse-strings: then-senior producer at RTÉ Cork, David Bickley, began to inquire as to the identity of this serial cross-town taxi-taker. “Who is Finbarr Creedon?” he asked The Swamp’s producer, who gestured to the dog.

“So they put up this sign in RTÉ that said, ‘No Taxis For Dogs,’” Creedon concludes with a note of triumph in his voice.

And on the subject of dogs…..he launches into another story.

This one is about his uncle Jeremiah, who had lived an almost hermit-like existence in a shed in Inchigeelagh, the old country, a veritable nest of Creedons, as anyone who has been through the village can attest. In life, Uncle Jeremiah was both burdened with a religious mania and beloved by animals, with whom he shared an uncanny power of communication.

When he was dying, all the Creedons - most of the village, then - gathered around the small shed in which his deathbed lay. Most, of course, couldn’t fit in.

“So how they all knew when he finally passed, was that a howl went up amongst the dogs in the village,” Creedon says. “And it rippled out into the townland all around.”

The hairs on my arms stand up and Creedon sits back, satisified, with a pause. “Now, of course, someone could have just kicked a dog in the village,” he finishes his tale.

Both stories, indeed, so many of the anecdotes that he recounts with relish, could easily be short stories of his own devising: imbued with a keen eye for the idiosyncratic, the quasi-mystical, the ridiculous or the downright odd.

We associate magical realism in fiction with South American greats like Gabriel Garcia Márquez and Isabel Allende, but Creedon has his own uniquely Corkonian brand of magical realism that you often find in his novels and short stories.

Creedon grew up swimming in a ceaseless, swift-flowing stream of stories like these, in the informal oral storytelling environs of his parents’ city centre shop.

Inchigeela Dairy

His parents ran the Inchigeela Dairy on Devonshire st, which had morphed from dairy to corner shop serving the busy maze of streets just north of the Lee. It sounds like a chaotic early existence.

“There was my mother and father and twelve kids and a few aunts,” he says. “It was a busy house. The shop was open from maybe six in the morning until midnight, and the front of the house was just open to the street, basically. It wasn’t a place that you’d be sitting around reading books, but what it really was was a place with storytelling.”

“I don’t mean Seanchaí-style storytelling, but people were talking at the shop counter, talking all the time. My father was a great man for talking.”

My beautiful Launderette

Knock on the gate outside Creedon’s city centre home and you are admitted to an unlikely little oasis that he has created: a small yard has been transformed into a tranquil garden, with tall bamboos and a profusion of flowers.

His living room is filled with books, tasteful knickknacks and comfortable chairs. There’s a banging coming from outside: the builders are in, renovating the exterior of his house. We settle ourselves for a chat, seated directly above what was once Creedon’s No 1 Launderette.

Having emigrated to Canada in his late teens, Creedon returned to recession-riddled 1980s Cork when his mother became terminally ill. The dole queues were huge. Creedon had a brainwave: he would avail of an AnCo government grant for starting your own business, and he would open a launderette.

Why, was he particularly good at washing clothes? He laughs.

“It’s something I’m good at, but I think that came about through experience,” he says. “I just saw an opening, because back then, not too many people had washing machines. Even B&Bs and football teams and things, small hotels, all had their stuff laundered.”

So Creedon’s was one of a large number of launderettes in the city. “There were two in Blackpool, one in Shandon Street, one on MacCurtain Street,” he says. “There was a mushrooming of launderettes for a while, which ended when affluence arrived and washing machines became more prevalent.”

The launderette became something of a hub for arty types: Backwater Artists Studio opened close by and the whole area around St Lukes was flatlands, the late Georgian terraces stacked on the hillsides crammed with cheap bedsits, bedsits that have featured in many of Creedon’s stories.

“They were perfect, in one way, for people like students, young artists, people who had just moved up from the country,” he says. “I moved into one in my early twenties, when I came back from Canada, for a tenner a week. All you needed was two weeks rent: now that option is gone.”

“I sort of think the current housing crisis saw the clearing of all that: I’m not talking about tenements, but about places that young, mobile people who are maybe passing through for a year or two could just rent for cheap.”

After the Ball

Even more important to the developing scene at the launderette, Creedon says, was the poster wall: in the pre-internet era, posters were how you found out about gigs and events.

“If there was a gig on upstairs in the Phoenix on a Tuesday night, that wasn’t going to be on RTE or in the paper,” he says. “People would stick their head in, and then they’d tell you about something else they’d been to see the week before that sounded interesting.”

It was while sitting in his launderette that Creedon began writing, and penned the first tale from the collection that would become Pancho and Lefty Ride Out, After The Ball, the tale of a street once full of children playing which, true to Creedon’s own lived experience, fell silent following a tragic accident.

You can hear Creedon discuss this story, and how his first collection of short stories found their way into print, in the podcast above.

Passion Play, his first novel, was to follow in 1999: written in the same distinctly Corkonian voice, referencing the same streets and bedsits, inner city grime hung with the twinkling lights of the spiritual.

Creedon would never accept the title of Laureate for the second city, because he is far too modest, but his ability to capture Cork’s dialogue and oddball characters had already led to his radio soap, Under The Goldie Fish, becoming a roaring success on RTÉ Radio Cork. It would run for four years in total.

“The title refers to the curious weather-vane on Shandon's postcard steeple,” the Dubs at the Irish Times reported.

Creedon, although he likes to refer to himself as an “accidental author,” has worked away steadily since, picking up numerous awards and accolades, both in Ireland and internationally, along the way. His 2018 novel Begotten Not Made picked up an Eric Hoffer Book Award and was longlisted for a Dublin Literary Award.

Mrs Havisham’s Launderette

One day in the nineties, in yet another real-life tale that would fit right in in Creedon’s fictionalised Cork, he got up one morning and simply….didn’t go downstairs and open No 1 Launderette: he was done with his little business, and had become a full-time author, but for many years, it remained intact, the posters on the wall and the docket books behind the counter gathering dust.

“That was the mad thing about it: one day, I just didn’t open it,” he says with a laugh. “I just said, ‘I can’t be bothered.’ There were people phoning me looking for their clothes because they were still in there, and they were saying, ‘please,’ and I was saying, ‘look I just don’t want to go in there now.’”

“It was like Mrs Havisham’s wedding table when I went back in there a few years later. I’d been in to collect the post, but everything else was just sitting there.”

This was a curious approach to a career change, surely?

“Well, because I didn’t officially close down, it’s like the guy who gives up the job teaching and goes writing but holds on to his job. Maybe it was like a ten-year sabbatical, and I thought the day might come when I’d go back in again. It wasn’t consciously thought of that way, but I think I just left it there because it was still operational, in a sense.”

Six years ago, Creedon decided he needed the space. No 1 Launderette is now no more: the space below where we are sitting has now been converted to part of his living quarters.

The digitally remastered edition

If the quarter century milestone for Pancho and Lefty has left Creedon in contemplative mood, then it’s as good a time as any to explore what he says has been a time of unprecedented change for the second city. And one of the most dramatic changes has undoubtedly been the birth of the digital era and the rise of social media.

It’s a drastic societal shift that Creedon acknowledges in the 25th anniversary edition of Pancho and Lefty which has just been released: “New digitally remastered edition,” a sticker on the cover reads.

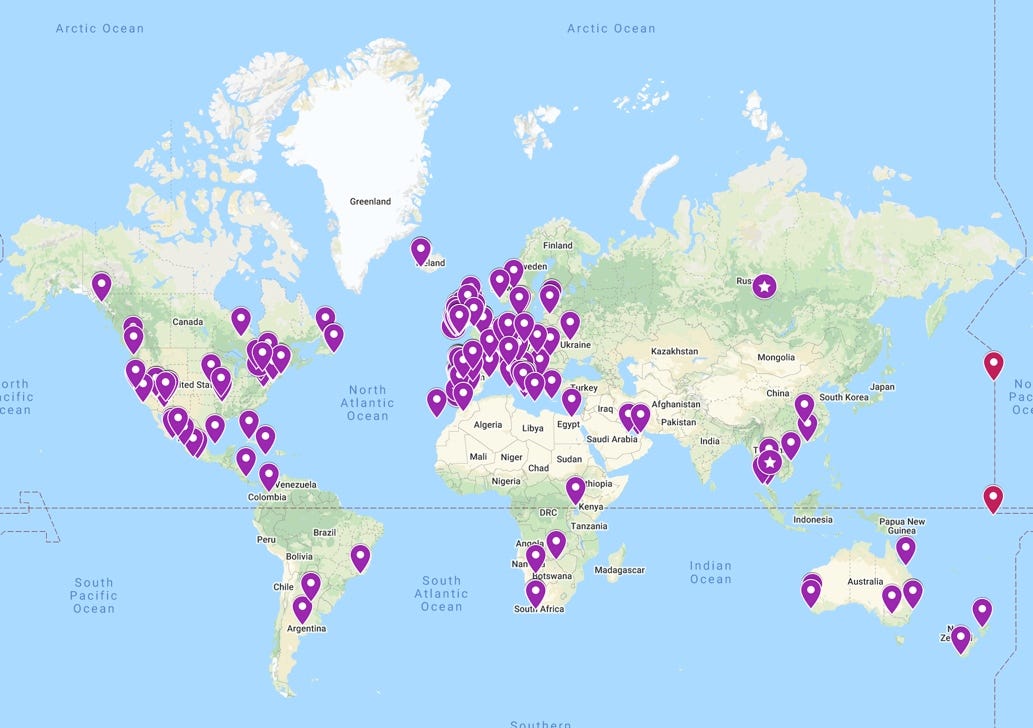

Creedon has become an adept user of digital tools: readers from around the world send him photos of his books, published by his own publishing company, Irishtown Press, being read in far-flung places on social media and these are added to his world book map on Google maps.

“I was very slow to the digital world but I can certainly see the benefits of it,” he says. “I’ve connected with people that I’ll probably never meet, from all over the world, and I think that’s a good thing. Change is something to embrace.”

The change, over the course of the past quarter century, has been profound and absolute, Creedon believes.

“The digital has changed us totally,” he says. “There has to be a civilised reaction if you’re in a room with people, and sometimes I think the digital reaction is very aggressive. Maybe that’s the way we’re going as a species, but maybe that’s ok. Maybe in the past, people would say nothing and then go home and give out to their partner about what they just heard.”

“I think it’s not possible for previous generations to even process, because that’s this generation’s karma. Where we are is where they’ll be, but they won’t be carrying the same baggage. If there’s one thing I regret about life, it’s death, because I’d love to be here in 100 years’ time to see where all this is going: social media, technology. It’s a pity I’m only getting into this now.”

Time is a measure of rates of change

Anyone who, like one of Creedon’s bedsit characters, has ever done a spot of 4am pondering-the-universe will have probably at some stage doubted the existence of most things, including time. And this is where physics provides unlikely comfort: time, when we get right down to it, is merely a measure of rates of change.

25 years’ worth of profound change have flowed down the Lee in the time that Creedon has been inhabiting the not-always-easy skin of the “accidental author.”

There are things to miss about the Cork of the late eighties and early nineties, and other things, like the crippling unemployment and poverty of the recession, not to miss at all. And there are lessons to be learned for the future.

“Back then, things were a lot more physical, and cause and effect were much more obvious,” he says. “but everyone was broke. Interest rates were at 20% and it was impossible to do anything.”

“We thought that would never end, just as the current generation thinks that whatever crisis they’re facing will never end, and just as the generations that came before faced all sorts of things, world wars and things, right back to the famine and before it. I think each generation faces its own Becher’s Brook, a hurdle that they have to get over or under or around. And we carry the lessons or the scars of it right through our lives.”

“Each generation carries a trauma. Maybe there’s such a thing of a trauma of excess as well, I don’t know: trauma doesn’t have to come from what we perceive as dark and difficult and dangerous times. It can come from a shift in equilibrium.”

It’s time to go, but it’s hard to stop: when Creedon gets into storytelling stride, tales pour out of him. Tales he may not have written and may never write, and some that he may indeed eventually weave into the warp and weft of the vision of Cork that he has created.

After the dog tales, he leans forward again, the same spark of energy igniting him:

“Have you even seen just one shoe in the middle of the street? Well, that’s how I knew that Covid was over…..”

The launch of Pancho and Lefty Ride Again by Cónal Creedon takes place on October 12 in Waterstone’s Cork at 7pm, as part of Cork International Short Story festival which runs from October 12 to October 16. More information here.

Share this post