The KLM: A den of inimitability

The unassuming pub near Kent Station has seen generations of rail workers, dockers, locals and even a crew from KLM come and go. They’ve all left their mark on the family-run institution.

For most people, the Lower Glanmire Road is an exit strategy. You put the boot down, headed eastbound, or to the capital five counties up the M8. It’s a wide enough road with traffic all headed the one way. Terraced houses line the street to Tivoli, a series of staircases and narrow streets link it to Montenotte perched above the city.

But those going at a more leisurely pace know that at number 141, a few doors up from where the rail line arches over the road as it winds its way to Cobh and Midleton, stands The KLM, which Fred and Mary Hackett have been running since 1991. The Lower Glanmire Road is tied to Kent Station and the railway in the same way as Tivoli is tied to the docks and the Hacketts are at the heart of the community in the Lower Glanmire Road. Their pub, The KLM, is known to generations of Corkonians and a few staff of the Dutch airline with which its shares its name.

There has been licensed premises at No. 141 since 1892 - before it was The KLM, it was called The White Elephant, and before that it was called The Green Dragon. Mary’s parents, Ferdie and Maura Hallinan, bought the bar in 1968, and it is very much a family bar: KLM stands for Kathleen, Lydia, Mary - Kathleen and Lydia being Mary’s two sisters.

Inside the KLM, pictures of times gone by dominate the walls, with one of the most prominent being one of Roy Keane with Fred and Mary’s sons Colin and Steve. The walls are covered in memorabilia and trinkets, rugby flags, Manchester United and Benfica scarves, news clippings about the KLM soccer team winning the Beamish Cup. There’s even cardboard cutouts of footballer Cristiano Ronaldo’s head.

Ireland’s oldest pub landlady

“I was born here (in Cork), went to England when I was five or six, came back here in about my twenties,” Mary Hackett says. “My Dad was a builder and a plasterer. We lived straight across from Ford’s factory in Dagenham.”

Mary’s mother Maura also worked in the bar, until her death in 2020 at the age of 102 and was well known for having the distinction of being Ireland’s oldest pub landlady, which led her to be featured in papers up and down the country. Fred and Mary’s son Steve named his bar after his grandmother, Nana’s on Douglas Street. A letter from President Higgins to Maura for 100th birthday is kept behind the bar at The KLM.

“She used to come down and fill a few pints, like now if it's quiet, you know, she did. She’d come down if we were upstairs and having our dinner or anything, she’d buzz the buzzer if there was a problem and we’d come down to her,” Mary says of her mother, “but, no, she loved it down here.”

“She loved all the railway fellas, and even when she died, I've letters we got from Dublin from the railway, you know. Lovely cards and acknowledged that she was after passing you know.”

According to Mary, it was hard work that kept Maura alive so long: “hard work and a drop of gin or a drop of whiskey.”

And then there were two

Where once public houses proliferated the Lower Glanmire Road, The KLM and the Station View Tavern are two of the last remaining.

“From the Station down to Myrtle Hill Terrace, there was fifteen functioning pubs for years,” Fred recalls.

Many of the bars lost were run by characters. Fred recalls a quote by a former resident on the road, Noel Kiely, “the further down Lower Glanmire Road, the tougher it gets. and I’m living in the last house.”

None of the publicans sounded tougher than Ms. Hyde, however.

“Ms. Hyde, she had a gammy leg, she had a pub just down there, and she’d hit everyone with the walking stick,” Mary says. “If you were going to mass at Saint Patrick's on the Sunday and Ms. Hyde was going up the steps and you went to give her a hand, she’d give you a clatter with the stick.”

Another former resident was Noel Kiely’s best friend, Tony Brosnan, known to all as Brossie. Brossie and Kiely were a duo who were often on the receiving end of the jokes, even in serious circumstances.

“Someone once broke into (Brossie’s) house that he was renting, and one of the other characters coming in here (to The KLM) said, ‘the fella who broke into Brossie's house said he took one look at it, and he felt sorry for him, and he left a tenner,’” Fred said.

The pool table

The pool table in the KLM is one of the bar’s focal points, and every Christmas, Fred and Mary organise a popular pool tournament. At the end of November, Fred puts the draw together. One year, they used the draw to play a prank on Brossie and Kiely.

“We rigged the draw, if you like, so that Kiely and Brossie would be out first, but everybody knew that was going to happen except them. And Kiely and Brossie, they were drawn together,” Fred says. “Of course, they were the best of buddies, but they couldn't stop arguing!”

“We had a referee and everything arranged, so anyway, we said to one of them: when you come into play, make sure you have a shirt, tie and waistcoat on, and chalk in the top pocket, and don’t say anything to the other fella, but then the other fella was told the same! So the two of them arrived in, took off their jackets, and they just looked at each other!”

“Colin, my eldest, used to work Sunday mornings, and he used to love coming down because they’d all be down here telling jokes,” Mary says.

“You’d be hysterical, you wouldn’t pay to go to the Opera House with the carry on that was going on!”

The railroads and the docklands provided the area with most of its industry, and supplied the KLM with many of their patrons. The railway workers were the most persistent.

“All the Dublin train crew used to stay in the dormitory across the road which has been knocked down, and this place would be full every Monday, Wednesday and Friday, of the Dublin train crew, because they’d be overnighting.” They’d all be here playing cards and singsongs and playing pool and everything. That’s going back 25-30 years, for that to happen.”

The dockers would call in too, though their visits were always more brief and sneaky. “You'd have dockers in every big ship in, it was mostly on a Thursday for about half an hour. They’d come over at 5pm and be gone at half 5, about 25 to 30 dockers would come over for their break. You couldn't do that now!”

And of course, with the pub sitting on the main road to the east, you had many passers-by stopping in on their way home from work. “All the crowd in Glanmire, a lot of them worked for Beamish & Crawford’s, a lot of Glanmiremen at that time, going back years. They used to call in on their way home, but you can’t now,” Mary says.

“Years ago people would call in, after finishing work, they’d have two pints, and be quite happily driving home, minding their own business. But if they were to do that now, they’d be in trouble,” Fred adds.

About those three letters

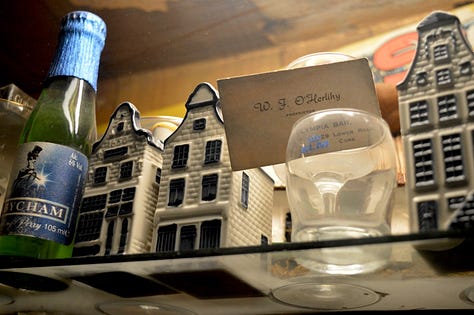

On the face of it, one of the most intriguing things about The KLM is its name, which it shares with the Dutch airline: Koninklijke Luchtvaart Maatschappij. It's a connection that has been picked up by others too, and KLM Airlines related memorabilia can be seen around the bar. The bar even hosted a KLM staff outing once.

“They didn't fly into Cork, but it was a cargo plane that was diverted for some mechanical reasons, and the crew were put up down at the Silversprings, and they got a cab from the airport and as they passed they went ‘The KLM!’,” Fred says.

“So they arrived in, and they were asking about the history of the place. Mary's Mum was there. She was telling them that she named it after the three daughters.”

“They wanted to know in case she took their copyrights!” Mary adds.

The crew said they’d put the story of the bar in an article, and how they came across it. They had a few drinks Mary said and headed back to the hotel and they thought nothing more of it, but a couple of weeks later “this letter came in, KLM, the little crown thing, and that was the inflight magazine that they sent us.”

Like family

It’s the regulars and the community around the pub that the Hacketts feel most attached to.

“You have to look after your customers,” Mary says, adding that Fred would go out of his way to look after the locals. He sees them so often that he knows their routine, and he knows when something is wrong.

“I’d get the papers for (Kiely) on Sunday morning. I'd go to the station, it was their local shop, and I’d get the papers, I’d get my own papers and his papers. And Sunday morning came anyways, he’d always leave the money there for us. He left here on a Saturday afternoon, about half two, three o'clock and he went home.”

“Sunday morning came anyway, I opened at half 12, no sign of him. One o'clock, no sign of him. Normally he'd be on the phone, ‘I'm not feeling great any chance someone would drop the papers down to me’. Half one, nearly two o'clock, I knew there was something radically wrong when he hadn't made any contact. I rang his landline and I rang his mobile, no answer. So I rang his home help, she went down and he was dead in the hall, after leaving here. He took a naggin away with him, and a bar of chocolate and a packet of crisps and they were still in this pocket, and he still had his coat on. He just got in the hall, closed the door and bang,” Fred says. “But they reckon 20 minutes later, he’d have unfortunately died there at the counter.”

For those living alone in the neighbourhood, the Hacketts feel a sense of kinship and responsibility.

“Brossie and Kiely, when they were alive every Christmas I’d always give them their dinner. Colin and Steve, they’d run down the road with their dinners to them,” Mary says,

“And I still do two, there's two on the road that I still give dinners to every Christmas day.”

Maybe Noel Kiely was talking more about life than the Lower Glanmire Road when he said “the further down the Lower Glanmire Road, the tougher it gets”. Thank god then for halfway houses such as The KLM.

From the archive:

Shine bright, The Constellation

The Constellation, on Watercourse Road in Blackpool, is both a sitting room and a pub. Or a sitting room in a pub. It’s set in the old front room of an 180-year old stagecoach house. Back in the day, horses coming from Mallow would be tied up in a laneway at the back - …

Brilliant a great read have to love the stories of the real characters of a long lost generation well done.