The French Connection

Part two of our exploration of Eirgrid's Celtic Interconnector, which is proposed to connect Ireland to the European energy grid, continues with a look at local community responses.

Dear Taoiseach

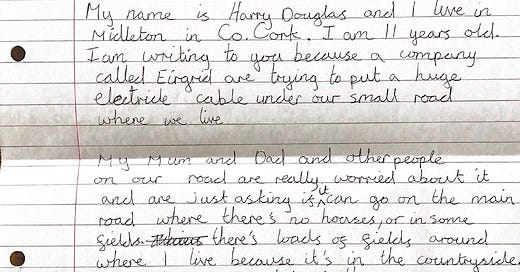

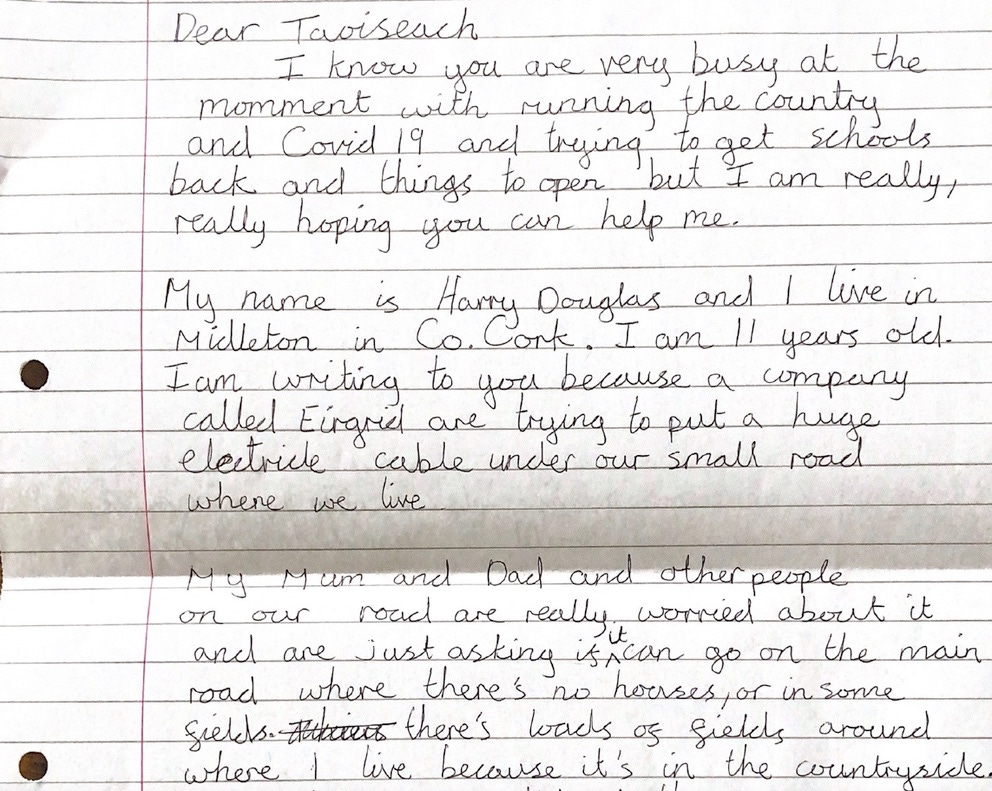

A few months ago, while Covid-19 “homeschooling” was still underway, 11-year-old Harry Douglas sent a letter to Micheál Martin.

He had a simple request, politely phrased: would it be possible for Eirgrid, the semi-state company responsible for building electrical infrastructure, to put their electrical cable across some fields instead of under the road running past Harry’s house?

Harry’s dad is Mark Douglas. Mark works for a big tech company and Harry, now 12, is one of two children; the family moved to a quiet rural lane in the East Cork Townland of Churchtown, to a place called Roxborough outside Midleton, four years ago.

It’s a lane like so many others in the Irish countryside: hedgerows and rolling farmland, some potholes, dark wintry trees sketching frown lines on grey skies.

Turning off the N25 at the Two Mile Inn on the way to meet Mark and his neighbours, it’s hard to miss the large sign of protest in the Cork colours. “No Eirgrid Interconnector on our road.”

Mark has joined his neighbours, Tom and Margaret Fitzgerald, who live at the other end of the road known as the Shanty Path. Tom keep horses on his farm; his business is called Roxborough Stables and the couple have lived on their farm for over 40 years.

Last week I wrote about the Celtic Interconnector which Eirgrid is planning to make landfall at Claycastle beach in Youghal. The €930 million infrastructural project aims to connect Ireland to the European grid via Brittany, overcoming energy security concerns raised by Brexit and touted to reduce Irish energy costs, although read the CRU’s cost-benefit analysis of the project to see vagaries about this.

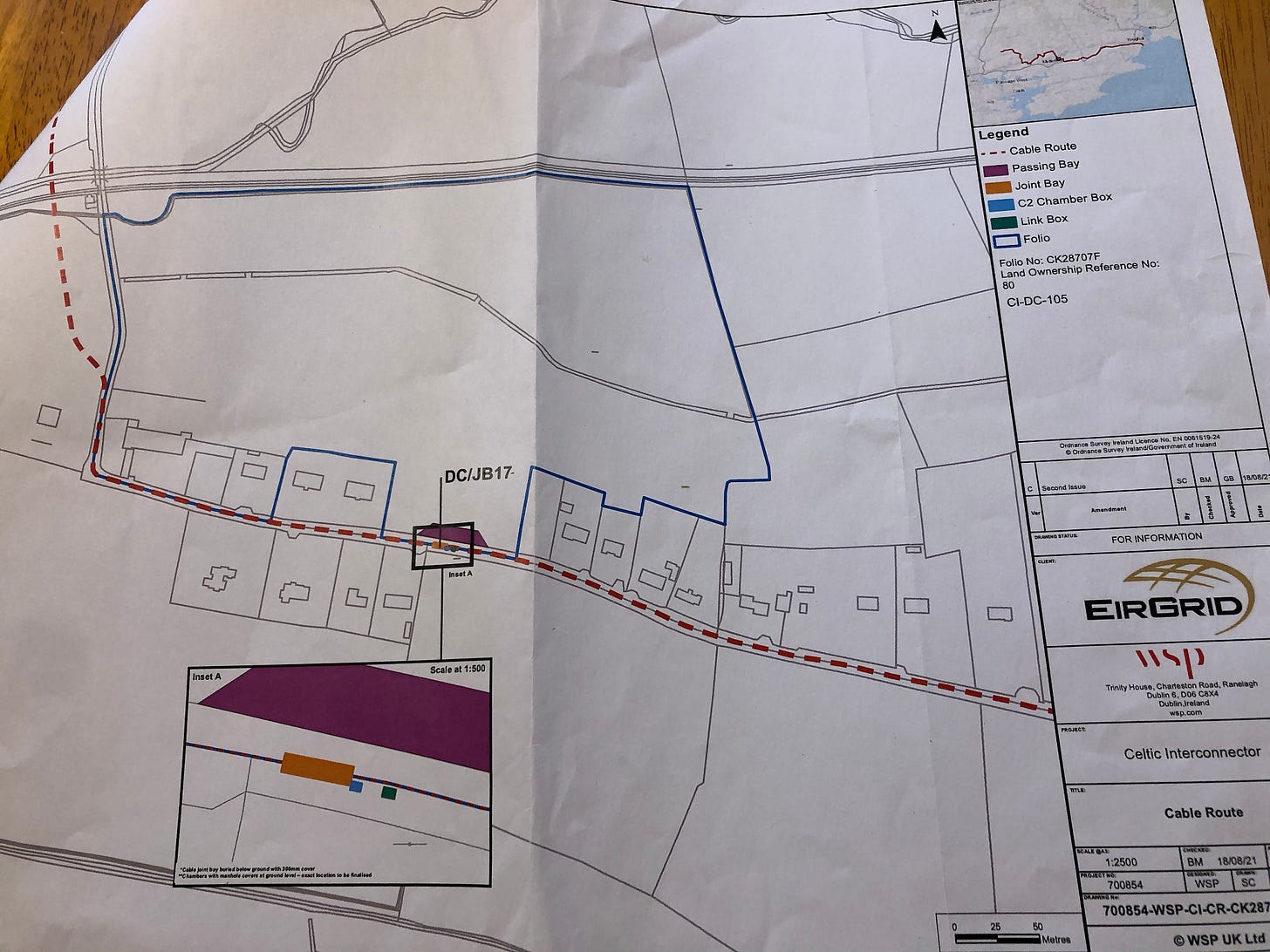

From Youghal, a High Voltage Direct Current (HVDC) cable would bring any power flowing from the French side across land to the former Amgen site in Carrigtwohill, to a new station where the electricity would be converted to Alternating Current (AC), before continuing to the substation in Knockraha in North Cork to connect to the national grid.

At the link above you can read a full interview with Eirgrid spokesman David Martin.

Towards the end of our interview, because I have been perplexed by the absence of coverage of such a huge and historic infrastructural project, I asked him if the planning application lodged in July had been subject to many objections. He told me that, in the scope of his experience, this project had received relatively few objections compared to other planning applications. “Anecdotally, there haven’t been a lot of submissions on this,” he said.

Mark, Tom, Margaret and other Churchtown residents say they don’t want Eirgrid’s HVDC cable running close to their homes; they don’t trust that the cable’s Electro-magnetic Fields (EMFs) are harmless and they have asked Eirgrid to route their cable across farmland, further from their homes.

On the Shanty Path, as with so many Irish roads, around 34 houses are largely clustered along the roadside and some residents have front doors within 20 metres of where the cable would run.

But Eirgrid have said no: the route down the Shanty Path is their “preferred route.”

Mark, Tom and Margaret all say communication with the semi-state has been difficult, that they feel their concerns have been ignored, and that not all the neighbours have been in receipt of the same information consistently.

Mark’s first contact with Eirgrid, the first time he heard tell of the project, was this year, although Eirgrid held a public consultation in 2019.

“50% or less of us received a letter this year, and there was still no definite route described,” Mark says of his first notification that the Celtic Interconnector cable was proposed to run past his house.

“I contacted Eirgrid to see what was going on and the rep said they’d had loads of consultations and kept everyone in the loop, end of story. I thought it might be me, because we’d only moved in about four years ago so I thought maybe this had been going on for years. But when we got on to neighbours I discovered a lot of them were hearing for the first time too.”

Tom Fitzgerald says he had an altercation with an Eirgrid representative outside his house: Tom was offered €7,000 by Eirgrid to locate a passing bay on his land, but he declined: “I told him that there were other routes and he said, ‘but they’re on private property,’ and I told him my property was private too.”

Although Tom made it clear to Eirgrid that he wasn’t open to a deal on the strip of land outside his property several weeks before the planning application was lodged, he was bewildered and angered to find that the passing bay on his land still featured in drawings Eirgrid submitted to An Bord Pleanála.

Eirgrid have been at the centre of acrimony and dispute about their projects before. The process of laying the so-called East-West Interconnector with the UK saw residents of Rush in North County Dublin protest against the cable, again citing health concerns.

“There’s been fights, marches, protests on many of their projects, like in Rush, so this is not new,” Mark Douglas says. “But they don’t seem to learn, it just seems to be a case of, ‘this is our decision.’”

Following consultation with residents, Eirgrid published a review of the available route options at the end of March 2021 and found in favour of their own preferred route. A month later they held two public information “webinars.” It’s easy to see why Roxborough residents could take umbrage at the terse statement released by Eirgrid following their review.

“I am happy that our review considered their opinions and suggestions for a different route,” Eirgrid’s Chief Infrastructure Officer, Michael Mahon, is quoted as saying in the statement. “While this review process did confirm our original route as the right one, I am satisfied now that all potential alternatives have been explored.”

The Roxborough residents don’t accept Eirgrid’s decision and say their justifications are vague. They insist that a route across farmland is viable and is a better option.

“We did have options,” Mark says. “There’s a route that misses all the houses and both the landowners have said it wouldn’t be a problem. But they only want to use this land and nowhere else.”

There was even the option to run the cable alongside the Youghal to Midleton Greenway, although Eirgrid examined this option and said the proposed local authority lease duration for the Greenway would be 25 years and that with a lifespan of 40-60 years for the cable, the two time frames are incompatible.

In November, the Roxborough residents heard from An Bord Pleanála, who told them they won’t hold an oral hearing. They don’t explain why, simply writing, “the board consider that the application can be determined through written procedures.”

Mark acknowledges that Eirgrid have addressed fears about Electro-magnetic Fields; when Rush residents objected on these grounds, they produced a document with statements from the WHO, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and others stating that Electro-magnetic radiation at a level of that put out by the HVDC cable is not of health concern.

Mark is not convinced. “Most studies are of high-level, short-term exposure,” he says. “What about low levels but extremely long-term exposure, like living right next to a cable? In other countries, they don’t put schools, nurseries or hospitals next to these things. What about the precautionary principle?”

Churchtown is an area of high Radon gas; this is another concern for Mark. He says some studies have shown that radon is attracted by electrical cables. The Shanty Path has water mains pipes running close to where the HVDC cable would be installed and Mark is concerned about the deadly gas accumulating in the water supply.

Mark’s son Harry may have written to Micheál Martin, but political support for the Shanty Path residents has been pretty nearly non-existent, Mark says.

“Initially we had some support, and at the first hurdle, silence. Dead, nothing at all. Ministers have just backed down. THere’s no fight in them at all. Why are they literally bending over for this?”

The answer may be in the strategic background to the Celtic Interconnector; as outlined in part one, without the promise of access to a lucrative European market for Irish offshore wind, it’s extremely unlikely that massive energy investors like Shell and Energia would be attracted to invest in the south coast. The domestic Irish market is simply too small.

The Celtic Interconnector has EU backing and funding as well as being considered vital strategic development by the Irish government.

Eamon Ryan was highlighting Ireland’s commitment to renewable energy at Cop26 last week. Recent Marine Planning has carved out a space for offshore wind and exploration licences for a bank of projects stretching from Wexford to Kinsale are underway. Several of these offshore wind farms are foreseen to connect to the Celtic Interconnector at sea.

Just transition

Margaret Fitzgerald thinks the Celtic Interconnector is a done deal, the planning process a mere formality. “They’re going to win anyway. They just bulldoze their way,” she tells me in her kitchen, with a little shrug.

Several Youghal residents I spoke to off the record think the same; they are holding out for details of a community fund, reputedly of over €2 million, that Eirgrid has put on the table for local projects and amenities. Most of the people I spoke to, like Margaret, believe the Celtic Interconnector is a done deal and that ensuring that any negative externalities caused by the project - in the short term, Claycastle carpark will be out of use and there will be temporary disruption for water sports enthusiasts, as well as impacts on the N25 - are countered with investment in local projects.

But for the Roxborough residents, that money could be spent, if money is the issue, to ensure that the interconnector’s route is one they are comfortable with.

“We’re not against this project,” Mark points out. “We just want it put somewhere where it’s not unnecessarily close to houses. We think that’s reasonable and we know it’s possible.”

Much has been made of the concept of just transition in recent years as the increasing urgency of shifting human systems to truly sustainable models has become apparent. It is centred around the idea of an inclusive and collaborative approach, where some communities are not asked to carry the burden of a move away from fossil fuels. Just transition is not just a concept for the Global South or for oil and coal workers.

An Bord Pleanála are set to rule on Eirgrid’s planning application by January 2022.

Mark Douglas and Tom and Margaret Fitzpatrick say they will not back down if the board rules in favour of the cable route past their houses.

“We will absolutely appeal,” Mark says. “This is a ridiculous situation to be put in when there are alternative routes and we will fight for those alternative routes.”

Eirgrid, in the meantime, are adamant that disruptions will be minimal and that there will be no lasting impacts once the cable is laid.

“There will be no lasting impacts and that is a top priority for us,” David Martin told me. “There will not be any environmental impact on Youghal. The cable will come ashore and then it will be laid alongside the road network, as if there were gas mains being laid. That will go on for some time because it has to travel all the way to Carrigtwohill, but once it’s installed and done, it’s as if it was never there. There will be no lasting impact at all.”

The fundamental interconnector-ness of all things

(With apologies to Douglas Adams)

In Dungarvan, former town planner Jack Keating runs a charter fishing boat business. He’s lived near the sea all his life; he’s a qualified technical diver and his love for the marine environment is palpable even over the phone as he describes life at sea off the south coast.

“I’ve been so blessed to have witnessed the marine life here,” he tells me. “I’ve seen all the big creatures out there over the years. I’ve seen leatherback turtles, sunfish. The biggest creature I ever saw in my life was a fin whale that came straight across in front of my boat: the second-biggest creature on earth, and we were in 60 metres of water. That was the 15th of September 2020.”

“I’ve come across dolphins en masse, in their thousands. In a November many years ago, as far as the eye could see, I saw dolphins in a feeding frenzy. I saw them in their thousands that day.”

Tripe + Drisheen is of course supposed to concern itself with Cork matters, but when it comes to the Celtic Interconnector, the knock-on impacts for coastal communities are worth widening the scope for once. Concerns relating to the interconnector are very much connected to the concerns of community groups in Waterford fishing villages like Dunmore East and Helvick, where residents want a 22km exclusion zone for offshore wind farms.

Jack didn’t make a submission to the planning for the Celtic Interconnector, or to its foreshore licence applications, submissions on which are still open until December 6.

He had attended the public consultation meeting in Youghal in December 2019, where he spoke to senior project engineers and marine biologists and was assured that the “environmental impact assessment would be robust.”

Marine EMF concerns

“The electro-magnetic field is what I’m concerned about,” Jack tells me. “I’ve read umpteen literature reviews and there seem to be two camps; one camp says electro-magnetic fields are not an issue with regards to affecting marine species, and the other camp says that they do.”

At the public consultation, Jack was handed a sample of the HVDC cable to hold. “The copper core of it was as big as a large orange, and then there was about another ¾ of an inch of insulation in loads of layers: graphites and plastics and loads of materials,” he says.

“They told me the cable was being buried two metres deep with a special trenching machine. And I asked them if there was an electromagnetic field coming off it and they said there is, and that it rises about two metres into the water column. The majority of the fish are moving, foraging and feeding on the seabed. How are they going to react? They said there’s no impact. I told them I’d seen some studies from America that said it precipitated avoidance behaviour. They said they’d address it with robust research.”

But the promise of a robust Environmental Impact Assessment hasn’t lived up to Jack’s expectations: he says that as far as he’s concerned it’s a “box-ticking exercise” when it comes to EMFs in particular.

“There are 260 pages and pages 222-224 deal with the potential impacts of EMFs,” he says. “They picked a few species: Salmon, Eels, Lemon sharks. As a planner I would be saying, ‘this is the tip of the iceberg, where’s the robust analysis?’ They used studies from Scotland and Wales. They said there were ‘no notable avoidance behaviours’ in certain species.”

Jack is apprehensive about what he calls the “avalanche of applications” for offshore wind that will arrive on the south coast in the coming years.

He wants to believe in a robust planning system, in due process. “I’m not anti-development or advancement,” he says. “But the wind farm applications that are coming in are private sector, profit-driven and they will run riot if they are not held to account by proper conditions in the planning.”

As a former planner himself, he made a submission to the National Marine Planning Framework because of his concerns. “The conversation was if the offshore wind plans should be developer-led or plan-led,” he says. “Of course they need to be plan-led. If it’s developer-led, their sole goal will be profit.”

He says Energia’s desire to site their proposed development at almost unprecedented proximity to the shore - a little over 5km from Helvick Head - was explicitly justified on the basis of cost at a recent public consultation event held by the company that he attended.

“I was appalled that they were so upfront with their justification for having fixed structures on the basis of expense,” he says. “It was a purely economic consideration. From a planning perspective, and a rule of thumb embedded in European legislation, economic considerations are not considered until after issues of sustainability, environmental impact, etc.”

“Is it a done deal, a foregone conclusion, government promoted, government facilitated, government sweetened, encouraging private developer-led wind farms to exploit our natural resource in the cheapest way possible? That’s what it seems to be for me.”

Jack is not against wind farms per se but he wants to see them situated sensitively, with considerations for biodiversity prioritised over the cost considerations of multinationals.

“Did you know that all the gannets you see on the south coast, right up to Cork, come from the Saltee Islands?” he says. “They fly down the coast to feed. With things like that, we have no idea of the impacts if there are wind farms all the way along the coast. You can say, oh, gannets, they’re not endangered, but we never appreciate things until too late, do we?”

When it comes to the Celtic Interconnector, Jack’s concerns about potential subtle changes in the marine ecosystem in Youghal bay are unquelled, but he retains some hope that our planning system can at least enforce best practice, demand additional information and adopt a precautionary approach that balances the requirements of sustainable development with protections.

“We’ll give the planners in An Bord Pleanála the benefits of the doubt, but unfortunately in the world we live in, the inspector can make a report and ask for further information and not be happy with it, and the board can overrule him and give conditions to grant it. I hope the planner will assess it fully. It needs to stand up to scrutiny.”