East Cork's Celtic Interconnector

In Youghal, Eirgrid's €930 million, 575km subsea cable connecting Brittany and Ireland is vital infrastructure for the power companies planning on capitalising on Irish wind power.

Against the backdrop of the Irish target of 70% renewable energy by 2030, an interconnector that’s proposed to make landfall in Youghal raises interesting questions about the future of the south coast for offshore wind developments, including some surprising details:

Ireland will pay two thirds of the cost of the project after EU funding while France will pay one third

Irish energy consumers will repay the cost of the state-backed project in their electricity bills but Eirgrid say bills will be cheaper

Project is hailed as a step towards decarbonisation, but no carbon life cycle analysis of the project has been conducted

Brittany’s only power stations are gas-powered

Youghal was once as important a port as Cork city, if not more so. And now the East Cork seaside town is set to play a large, but largely unexamined, role in plans to exploit the wind resources off Ireland’s south coast.

The application for a foreshore licence for a large infrastructural project called the Celtic Interconnector is underway in Youghal: public submissions on the foreshore licence are open until December 6.

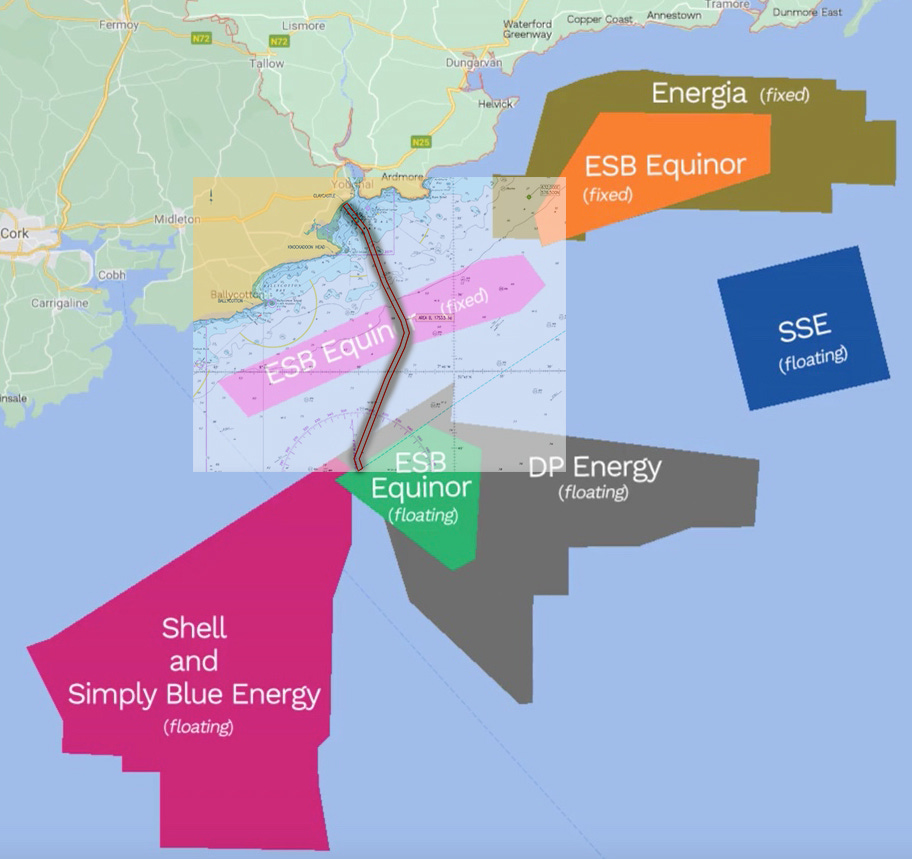

Essentially, the Celtic Interconnector is a large undersea cable that would connect Ireland and Brittany, with the capacity to import or export 700 MW (enough to power about 450,000 homes) in either direction. It’s envisaged that at least three of the power companies who are currently in the process of seeking exploration licences to develop offshore wind plants would ultimately connect to this cable.

The proposed route of the cable would bring it onshore to a converter station at Claycastle beach, and onwards to the substation at Knockraha in North Cork for connection to the national grid.

Eirgrid, the commercial semi-state power infrastructure company, are behind the project.

Eirgrid spokesperson David Martin was keen to highlight the potential benefits to Irish energy consumers of the project; he says a direct connection with Europe, especially post-Brexit, will bring energy security and will result in cheaper power bills for Irish customers.

“It provides a direct link to continental Europe for our electricity connection,” David says. “It will bring a downward pressure on prices and it will improve the security of our supply, because we are an island and all our European neighbours are heavily intertwined but we’re not, we’re kind of isolated. This will bring us into the European network.”

A two-way street

Eirgrid’s planning application, lodged in August, says it the Celtic Interconnector will “Support Europe’s transition to the Energy Union.”

While local communities along the south coast who oppose plans for a bank of offshore wind farms have told me they fear that the Celtic Interconnector will primarily be used to export Irish wind energy onto the larger French market, David says the interconnector will function as a two-way street, importing French power when Irish winds aren’t blowing, and exporting surplus energy when they are.

“Typically, we will be able to import energy from France when it’s cheaper than here and we have a huge amount of wind generation in Ireland and sometimes we don’t need it all,” he says. “So if the wind is blowing in the middle of the night when there isn’t a huge demand for electricity, we can export it across to France.”

But the Celtic Interconnector is, he acknowledges, hugely important in making the proposed offshore wind developments by companies including Shell, Energia and SSE a “more attractive commercial proposition,” allowing them to access a market far larger than Ireland.

Costs

The cost of the project has been estimated at €930 million in total, although the cost-benefit analysis published by the Commission for Regulation of Utilities (CRU) has acknowledged that it could cost €140 million more than this.

The EU will fund half of the project cost but of the remainder, Eirgrid are paying two thirds while French transmission operator RTE will pay one third of the bill; this is because, according to the CRU, Ireland stands to gain more from the connection than France does.

Ultimately, while Eirgrid will borrow their share, Irish consumers will pay through their electricity bills, David tells me.

“It’s not being funded by the Exchequer or by the State; Eirgrid are going to a European funding bank for big infrastructural projects in Brussels and we will be borrowing money from them; we’re not asking the tax payer to fund it. The revenue will come back through the electricity bills that you and I pay: a very small fraction of the bill will go towards it.”

When it comes to the promise that Irish consumers will benefit from cheaper power, David says it’s a matter of “the fundamental laws of economics. It’s supply and demand and this is going to increase the supply. We’ll only be importing from France when it’s cheaper than using our own, so it will definitely put downwards pressure on the prices.”

However, is the notion that the cable will lead to cheaper power for Irish consumers in a market driven by private multinational energy traders a shoo-in? Customers in southern Norway actually experienced a 14% price hike this spring following the connection of the Nordlink interconnector with Germany became operational: analysts say the increase is being caused by convergence between Norwegian and German prices.

While benefits do normally accrue to the country with the higher initial power costs, in this case Ireland, the CRU’s cost-benefit analysis notes several areas of uncertainty. “Celtic’s benefits are uncertain, and the modelling is sensitive to the inputs assumed,” the CRU report reads.

This week, Norwegian wind company Equinor pulled out of their planned Irish collaboration with the ESB in Clare and Cork, citing Irish planning regulations as an obstruction to their proposed operations.

“In scenarios with slower renewable deployment, benefits from Celtic might be lower,” the CRU report acknowledges. Other issues it highlights are:

· Ireland is a small country, so the investment cost would be a burden to a relatively small number of Irish consumers in comparison to other larger EU countries.

· Celtic’s regulatory model in Ireland, as proposed by EirGrid, is very light on detail at this stage. Further work is required to fully understand its potential impact on consumers, including whether, and to what extent, any cost overruns would be shared between EirGrid and consumers.

· In the worst-case scenario, that is, where 70% of project costs is allocated to Ireland and the expected benefits from Celtic are the lowest, Irish consumers might have to bear as much as €418 million

· The CRU is of the view that if Ireland were to agree to cover 70% of project costs, we would then require at least €418 million from the CEF grant to mitigate the risk of a negative consumer impact in case the benefits from the project turn out to be significantly lower than expected. This level of grant for Ireland would ensure that including Celtic in national tariffs does not represent a disproportionate burden for consumers.

No carbon life-cycle analysis

The Celtic Interconnector is expected to have a 40-year life expectancy and annual operating costs of €8.4 million.

575km of cable manufactured from a variety of metals, plastics and other raw materials - 10% of all global carbon emissions in 2018 came from mining - the energy costs of digging a trench at sea to sink the cable, including diesel-powered ships, concrete for construction and road works to lay the cable from its landfall at Youghal to Knockraha over 30km away.

Many people know that most French power comes from nuclear power stations but in Brittany, there are only two power stations and they are gas-powered: both are nearing the end of their life cycle and a third power station, also gas-powered, has been proposed.

If the decarbonising impacts of the Celtic Interconnector rely on Irish wind generation, how long will it take the project to compensate for the carbon cost of its construction, not to mention maintenance and eventual decommissioning? Will it begin to make carbon gains within its 40-year lifespan, under a variety of scenarios where Ireland adopts renewables more or less quickly?

The astonishing answer is that no-one knows.

Eirgrid says their project will “help achieve our climate objectives” but you may be surprised to learn that there has been no life cycle analysis of the carbon footprint of the project.

“There’d be a carbon cost associated with it, but I actually don’t know if there’s been an evaluation done on that,” David told me, later confirming that no life cycle analysis exists.

This is part one of a two-part story on the Celtic Interconnector. Watch out for part two in the coming days.

Great information, a lot to consider that’s not being covered by other media