Making History review: Game of Thrones without the gratuitous sex. And dragons.

Des Kennedy kicks off his Everyman tenure with a spirited update of Brian Friel’s play in a production that's politically charged and wrestles with the timeless question of what it means to be Irish.

Trying to appear on the right side of history is a performative act, which in the past, used to at least allow for the slow passage of time.

Nowadays, this manoeuvring has accelerated to the nth degree in the form of what is commonly referred to as virtue signalling. It’s carried out in a desperate attempt to bolster one’s social and moral standing in a fragmented society largely devoid of critical faculties.

Undoubtedly, it is one of the more nauseating aspects of an age dominated by the conflation of facts and truth, and has led to collective reactions to historic events becoming no more than a series of automated responses, dictated by a prepackaged and prescribed official narrative, which is only ever a mere click away.

In choosing then to stage Brian Friel’s Making History as the first production in his new role as artistic director of The Everyman theatre, Des Kennedy has made an interesting and timely selection, as central to the action in this play is the question of who is best placed to record history and how should it be told.

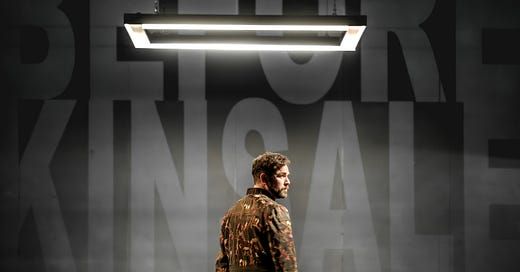

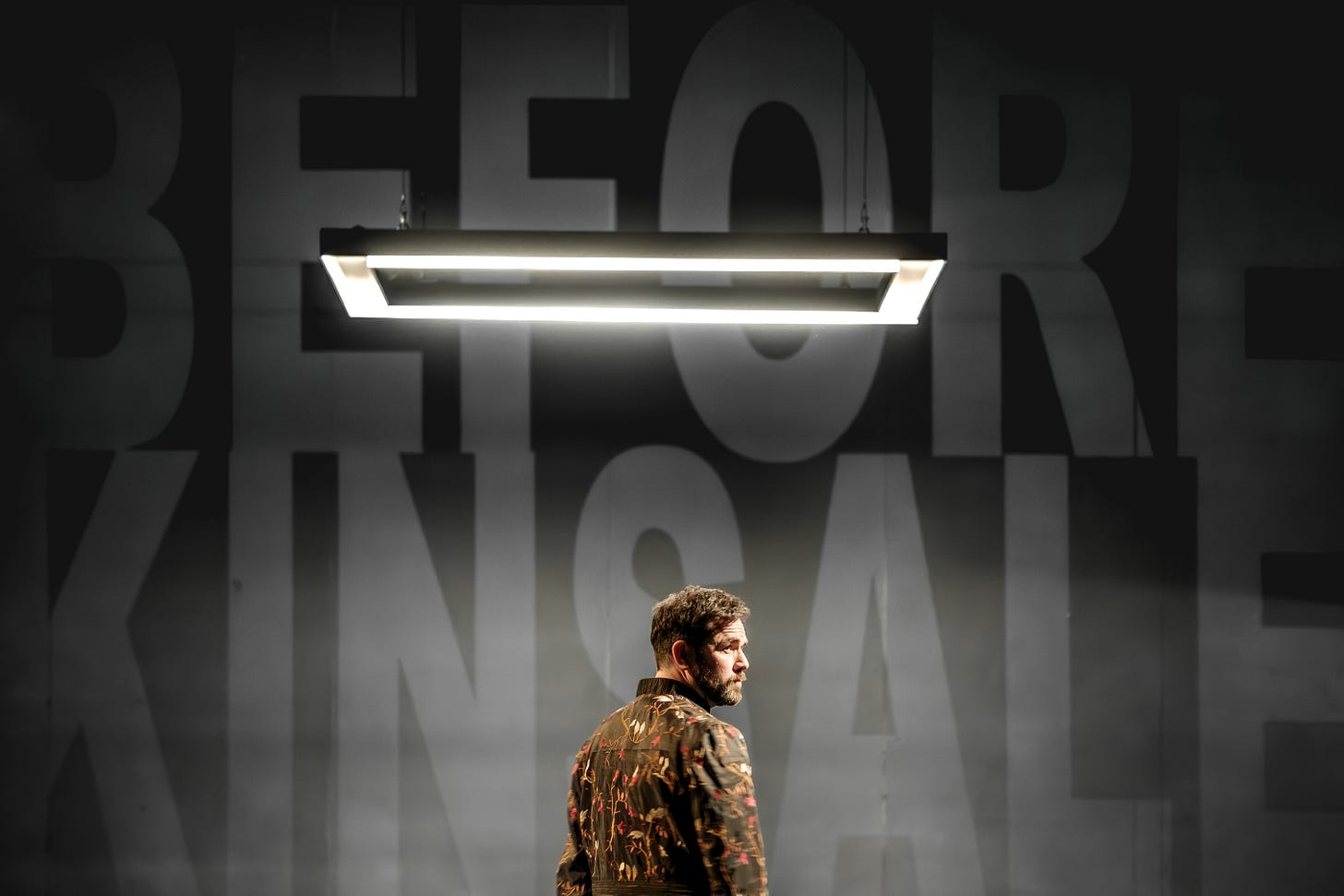

The story begins in Dungannon Co. Tyrone in the grand house of Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone played by a suave and at times almost borderline Matt Berryesque, Aaron McCusker.

O'Neill finds himself at a crossroads where his personal desires, especially his ambitions for power, conflict with the collective fate of his people. He has just married for the third time to the much younger daughter of his enemies, Mabel Bagenal (Liadán Dunlea) and is delighted by the charm of the ‘new-English’ woman.

Dunlea portrays Bagenal as gentle and loving but capable of being firm and speaking her mind when the occasion calls for it. Although not as central as O'Neill, she and her sister Mary (Martha Dunlea) nonetheless reflect the social dynamics of the time and reveal the personal side of historical figures, humanising them and providing insight into the emotional costs of the struggle.

While Friel asks to what extent is history made by individuals, and to what extent do individuals merely serve as vessels for history's grand narrative, this production seems to emphasize the latter and it does this mainly through some very specific costume choices.

Before the Battle of Kinsale takes place, McCusker is decked out in the marked clothing range popularised by Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy. The rambunctious, wine swilling Hugh O’ Donnell (Aron Hegarty) sports a Palestinian Keffiyeh, while in between scenes the actors wear hazmat suits when rearranging the stage.

All three of these items are overtly blatant political decisions suggesting that the right sides of history to stand on are immediately clear and obvious which is entirely contrary to what the play is all about. The hazmat suits in particular reinforce the wartime rhetoric which was employed during Covid and all three are ill-advised decisions which detracted from an otherwise engaging production.

An inspired decision on the other hand, was Kennedy’s casting in the final scene where three older actors play the roles of O’ Neill, his faithful servant Harry Hovenden and biographer Peter Lombard, earlier on played by a sullen Ray Scannell.

O’Neill is washed up in Rome, and is played to a tee in a show stopping performance by Denis Conway, who brilliantly conveys the intervening years of despair and regret O’Neill must have felt since the failure at Kinsale.

In an echo of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar where Titinius after learning of Cassius's suicide, expresses the end of an era and a descent into darkness “The sun of Rome is set. Our day is gone. Clouds, dews, and dangers come; our deeds are done,” O’ Neill too knows his days are numbered and is worried that Lombard (Peter Gowen) will not tell the truth of his life and make him out to be a hero which he feels would not accurately reflect his many misdemeanors.

It is a gripping end to the production, one which must also be commended for an excellent sound design by Mel Mercier and a very clever set design by Niall McKeever, especially the transition of the table between each act, which perfectly symbolises O’ Neill’s plight over the years.

For some people, the historical focus in Making History might be a bit dense at times, especially if you're unfamiliar with Irish history. However, Friel and by extension Kennedy, does a commendable job of making these events accessible, using them more as a vehicle for the personal drama of the love story between O’ Neill and his wife Mabel rather than as a lecture on Irish history.

In lots of ways, anyone who lays claim to being Irish is a Hugh O’Neill of sort, struggling to find a place in an Anglocentric world, caught in a spiritual vacuum and bombarded by propaganda and subsequent virtue signalling, day in and day out.

But what does it mean to be Irish? Is the idea of a united Ireland worth fighting for? These are all further questions the play poses and their answers remain pertinent today and indeed echo far beyond this little island.

If you like historical dramas that delve deep into the human psyche, especially in the context of political upheaval; think Game of Thrones without the gratuitous sex and violence, then Making History is worth checking out. Just ignore the costumes if you can.

Making History by Brian Friel runs at The Everyman Theatre until April 26. For more information an tickets visit the Everyman website.