Click play above to listen to the full podcast conversation with Fred Callow about his book and his life on Cool Mountain. Read on below.

There’s something funny about being given an Eircode to an address on Cool Mountain.

It seems to contradict the mythology of the place, somehow: to be altogether too on-grid, too firmly in the modern digital era for a place renowned for wildness and the rugged make-do lifestyle of its inhabitants.

Nevertheless, that’s what Fred Callow proffers over the phone, and I dutifully jot it down. It might come in handy.

It also seems odd that, when I tap the code into Google maps before leaving my home on the north side of Cork city the following morning, the bland female English voice tells me my journey will take an hour and seven minutes.

Cool Mountain must be further than that, surely?

I remember long and bumpy journeys down the “Bantry line” from the city as a kid, to visit friends of my mothers and play outdoors with children who were named after flowers and natural phenomena: my mother was part of an early wave of settlers who arrived in the seventies, mostly English with a scattering of Germans and Dutch, who were aiming for self-sufficiency and off-grid living in the wilds of West Cork.

My mum lived near Inchigeela, a few miles from Cool Mountain. Eventually she moved on, and we grew up in the city where she ran a health-food shop, but maybe once or twice a year we’d pile into our rusty banger and go on visits to the families who had stayed out West, built up smallholdings and started various small businesses.

They were hard-working, adventurous, resourceful and frequently misunderstood: their lifestyle as “hippies” was perceived to be one of free love and drugs, and while there was some of that, it was mostly about extreme resourcefulness, the acquisition of often dying skills, and replacing the creature comforts of a rapidly modernising Ireland with a DIY attitude when it came to everything from the homes they built or renovated to the food they ate and the clothes they wore.

Further waves of immigrants to Cool Mountain and its surrounds came in the Thatcher era and beyond, and for a time, the area, nestled in the foothills of the Sheehy mountains, developed a strong sense of community and an ethos all its own, even a community centre for a period of time.

Fred Callow was part of this later wave.

The modern world has contracted and become humdrum and predictable, I thought to myself, setting off past Ballincollig and turning towards Crookstown and Béal na Bláth, accompanied by the irritatingly soothing voice of my Satnav companion.

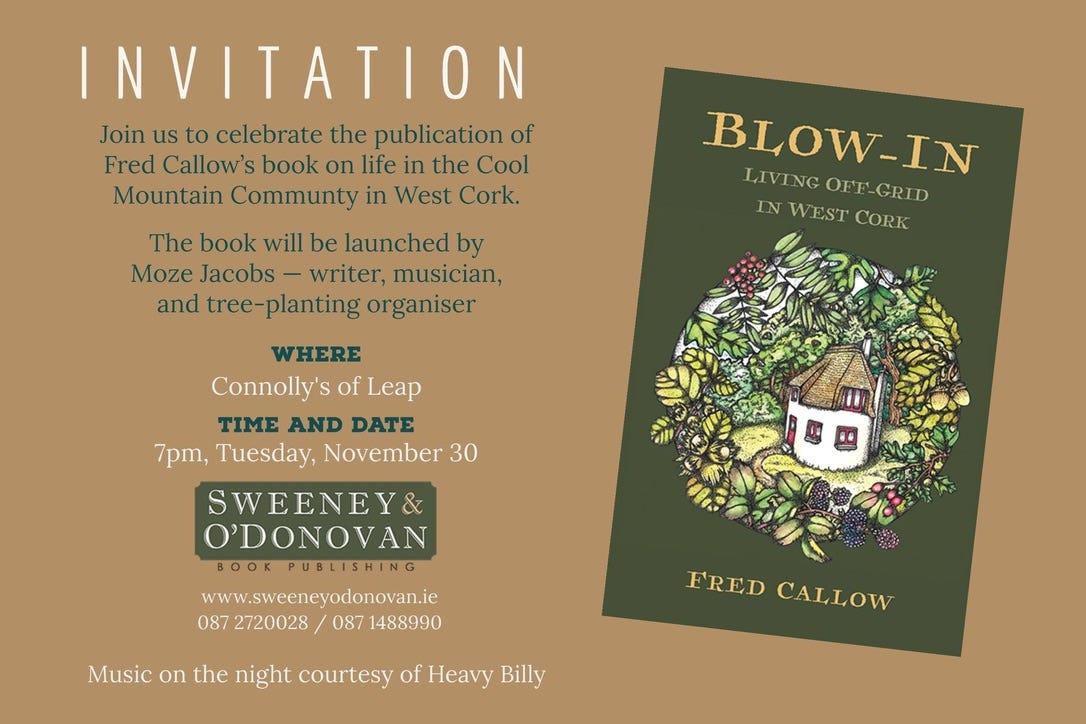

Modernisation, and the fate of the Cool Mountain community, and how the children and grandchildren of those who settled there have chosen to live their own lives, are all topics dealt with by Callow in his new book, Blow-in.

Blow-in is Callow’s memoir, his first book. It describes his time in Ireland from his arrival in the early nineties, through early years living in a van and busking, to working in forestry, through to becoming a family man and building his home on Cool Mountain.

It’s a fascinating first-hand account of a life rooted in personal politics; Callow, born on the Isle of Man, describes a mounting sense of unease with the job-marriage-mortgage triumvirate of the capitalist, consumerist status quo throughout his student days and early twenties. West Cork was his escape.

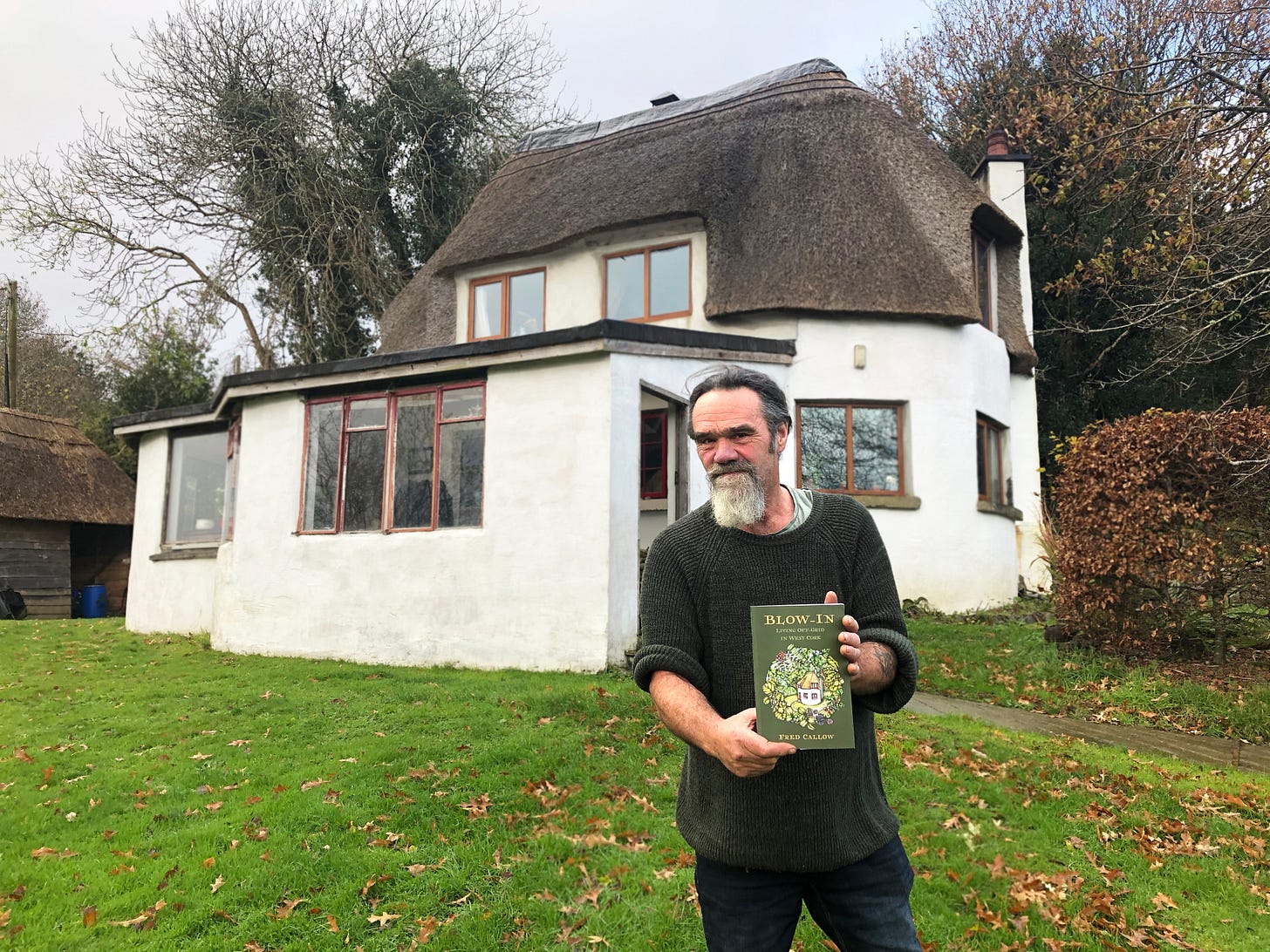

Callow is now 63 and a grandfather, although he’s a good poster boy for an outdoor, active life; with his muscular build, burly arms and still-dark hair, he could easily be ten years younger.

He greets me in the laneway to his home because, Satnav notwithstanding, I have still managed to get gratifyingly lost on the final furlong, up on the mountain where Callow’s neighbouring plots include successful and less successful attempts at self-builds, with houses and occasional mobile homes nestled in a series of tiny muddy lanes.

“It’s an opportunity to correct the record a bit,” Callow tells me of his book, making a pot of lethally strong black coffee.

Certainly, in Blow-in, you get the sense that Cool Mountain’s reputation amongst the press and occasionally with locals as den of iniquity and vice grates on him. The labels of Hippie, Crusty or New Age Traveller rankle and he’s definitely letting people know about the method to their perceived madness, the deeply held convictions and love of nature and freedom that were shared by Cool Mountain residents.

Creative life

This especially extends to the flourishing of a staggering array of creative and crafting pursuits on the mountain. Callow himself spent years performing with the five-piece Bog Band as well as busking and now, it seems, writing has become an extension of that creativity.

As he so astutely observes in the podcast though, it’s anyone’s guess whether the creativity of Cool Mountain inhabitants is what led them to rejecting a “normal” life in the first place, or whether the free choice of how to use your time involved in the lifestyle led to an explosion of creative pursuits.

“There’s so many people trapped in jobs they don’t enjoy, who might be very creative people but never get a chance to explore that,” he points out.

Trouble in paradise

Callow doesn’t skirt away from some of the harsher realities of the Cool Mountain community in his book: there was, at times, trouble in paradise. There was family dysfunction in instances, sometimes children who, he says, didn’t always receive the level of care they should have. There was even a murder, in the case of one much-loved elderly woman, who died in a fire started by her husband in 1996.

The community that worked together played together and partying was a part of life too; Callow describes it as being largely harmless and centred around home brew, cannabis and occasionally magic mushrooms, until, in the early ‘00s, a new generation started having loud raves. This, alongside the arrival of a few unsavoury characters, Callow credits with the bad reputation the community developed in some quarters, with the press pushing a sensationalist line, linking Cool Mountain to events and characters that were at times completely unfounded, and without journalists even attempting to contact anyone for comment in many cases.

Everybody wants to think their own way of life is best, don’t they? Everybody needs to know they’re right.

If you’re struggling under a €300,000 mortgage with a massive car loan and childcare bills, maybe the idea that someone can do what Callow has done is actually painful to behold; maybe it casts doubt on the choices you’ve made yourself.

It might be easier to label and dismiss people than to contemplate the fact that they might be right about all the capitalist, consumption-based model that they escaped, at a cost, and that you didn’t, at a different kind of cost.

Callow now has a day-job as a coach driver. His lifestyle may have lost some of its wildness in recent years, but it is still certainly at least free-range.

After our interview, we go on a short tour of Fred’s three acres: his polytunnel and veg patch, the outdoor composting toilet set under a separate thatch roof which converts shit to a harmless, odourless and useful compost that he uses to fertilise his trees.

He loves this land and he loves to share his plans for it. He points to different species of trees he’s planted, plans for a sauna and plunge pool, and a patch where one of his now-adult children hopes to build a separate home.

It’s interesting to view this entire tale, and Callow’s book, against the backdrop of what has happened to Irish housing and the Irish economy since the time Callow arrived in Ireland.

The Irish housing situation is now so heavily calibrated for profit that it’s a travesty, in which hundreds of thousands of homes lie empty while children sleep without basic dignity or privacy in hotels at the cost of thousands per week. The only political response to the weight of this suffering and trauma is to promise that more developers are going to litter the landscape with cheap, low-grade “new builds” from non-sustainable materials. It’s an economic, environmental and personal devastation.

Yet here is Fred, on a beautiful winter’s day, sitting in a home which cost him thousands. Not only warm, dry and built largely from reclaimed and renewable materials, but also extremely beautiful, constructed around a humane aesthetic, an homage to nature.

His house has a minimal impact on the environment around it. He has room to expand for family if he needs to. And he lives looking out over some of the most beautiful landscape in the country.

“I’ve chosen what’s right for me,” he says. “If someone can read about it in my book and maybe be motivated to do the same, I’ll be happy.”

Blow-in: Living off-grid in West Cork by Fred Callow is published by Sweeney & O’Donovan, a new small publishers specialising in non-fiction and based in West Cork. The book’s launch is in Connolly’s of Leap on Tuesday November 30 at 7pm. Keep an eye on Sweeney & O’Donovan on social media for a list of stockists of the book.