A jester in the court of the Crimson King

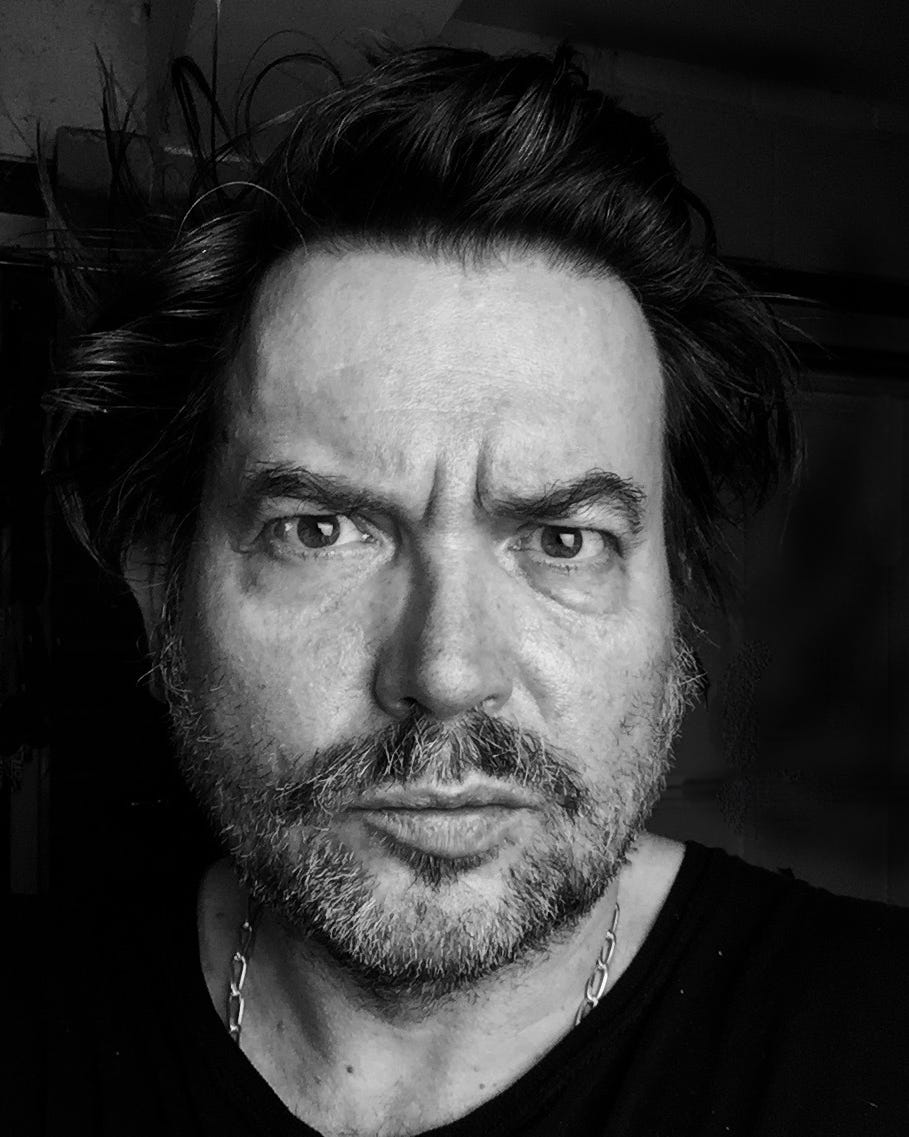

Director Toby Amies spent years filming cult band King Crimson for his latest documentary; writing himself in, he allowed himself to become the brunt of jokes and occasional swearwords in the process.

“I don’t welcome humiliation, but I welcome opportunities to grow, and I think that humiliation is a very good way of doing that,” Toby Amies, looming into view on Zoom, plastic framed glasses sliding down his nose, says with a hearty chuckle.

We’re talking about the director’s own role in his latest documentary, In The Court Of The Crimson King, which, on one level, is a 50th anniversary retrospective of King Crimson, the cult rock band which has been through many iterations since forming in the late sixties but which has always revolved around the central character of guitarist Robert Fripp.

But that’s only on one level. The documentary, filmed during the band’s 50-gig 50th anniversary tour in 2019, has been hailed by critics for its depth, its willingness to tackle not just rock’n’roll but mortality, ageing, and an eternal, almost spiritual struggle for creative satisfaction.

“It’s not only a film about a bunch of old men bitching about the past, and it’s not necessarily a film about an esoteric and stubborn rock band,” Amies tells me. “It’s a film about personal sacrifice.”

Even this doesn’t really go far enough; later in the interview he broadens this definition. At 55, Amies says, he’s only interested in making films about the human condition.

King Crimson, with all of their interpersonal angst, pre-gig nerves, divorce, endlessly practiced fretting techniques and obsessive fans, were the conduit for this.

“I want to learn about what it means to be a human,” he says. “Luckily I found the perfect band to do that with, as incredibly difficult and mind-fucking as they are.”

A jester in the court of the Crimson King

Part of the methodology used by Amies in this quest is to write himself into the story: his off-camera questions and comments, his interactions with band members feature frequently. In fact, these so often involve him being told to stop filming that he made a tongue-in-cheek mini “making of,” comprised of 45 seconds of him being told to fuck off.

“Yes, I was like the jester in the court of the Crimson King, or it was maybe the passive role of straight man in the court of the Crimson King, I don’t know,” he says. “There was a point with the editor where we sat down and took out anything that I said that I thought was a funny or clever or whatever. Because it’s not about be, it’s about them. Gags are better at the expense of yourself.”

These scenes in which Amies makes his own presence felt often provide welcome moments of levity in a film about a band in which interpersonal relationships seem almost unbearably intense. Fripp’s pursuit of the higher planes of musical release has left a scattered trail of over 15 bruised former band members in King Crimson’s half-century-long wake.

Amies’ modern form of roving Cinéma-Verité style is no doubt partly influenced by his own background as a presenter and VJ on MTV, but more so, he says, by years of experience working as a portrait photographer, learning new ways of meeting his photographic subjects half-way.

How a lot of photographers work, by focusing on appearances and only communicating with subjects to pose them, results, he says, in “pictures of people having their pictures taken.”

“I increasingly realised that I wanted to take a picture of a relationship I had with a subject. I’d spend a long time getting my subjects comfortable. You build up this relationship of trust with someone and ultimately you’re taking a picture of that relationship. Then, hopefully, if it’s a decent picture, the person looking at it has a sense of what it is to know that person. That, probably more than anything else, has influenced my process as a filmmaker.”

Nuns and cancer meds and rock’n’roll

In The Court Of The Crimson King is so very, very far from the shallow glorification of sex and drugs and rock’n’roll of which a depressing number of music documentaries were comprised for so many years.

Uber-fan Sister Dana Benedicta is one surprise: a nun with a passionate, beautifully articulated philosophy on aesthetics, interviewed by Amies in a chapel.

The film also captures keyboardist Bill Rieflin, former drummer with Ministry and R.E.M. amongst many other musical credits, in the throes of his battle with cancer in the year leading up to his death in March 2020.

In one memorable scene, Amies asks Rieflin for permission to discuss his physical health and the white-haired Rieflin, luminous with tight-jawed rage, rips into a list of the surgeries he has undergone, the pain he has been enduring, concluding with a furious “there, is that enough for you?”

His anger may seem directed at Amies, but of course, it’s not. It’s far more existential than that.

“It’s like seeing an angel before he’s made, isn’t it?” Amies says of Rieflin’s presence in the film. “There’s a Philip K Dick theory that we die at the point at which we gain enough understanding of this phase of existence, that that’s when the universe goes, ‘ok you’ve got this bit, you can move onto the next class.’ And Bill is such a good example of that. You don’t need to be here, Bill. You got it, a long time ago.”

“Apart from Robert, Bill was the only punk in the band.”

Amies appreciates this, being more of the punk era himself. He admits to not having been a King Crimson fan, or indeed having listened to the band renowned for their virtuosity and reverent cult following much prior to making the film.

He was commissioned by the band to make a 50th anniversary film having met Robert Fripp socially: they both live in Brighton, and Fripp watched and approved of Amies’ previous critically acclaimed documentary, The Man Whose Mind Exploded.

King Crimson funded the film and then “didn’t interfere at all,” Amies says. “They are fiercely independent, but that respect for the necessary independence of the creative process extends to you, even if you’re working with them. When we went over budget there was a bit of grumbling but apart from that, there was no interference at all. It’s been quite incredible.”

The Crimson King himself

Seeking and retaining Robert Fripp’s approval is a constant reference point for other musicians in In The Court Of The Crimson King. At times, Fripp comes across as Saturnine, even demonic: a controlling perfectionist who cares little for the finer feelings of the musicians around him. At other times, he is extraordinarily, movingly vulnerable.

Either way, he is a character who seems to hold inexplicable power over the creative people he works with.

Has Fripp watched Amies’ documentary, and what does he make of it if so?

“He’s said bits and pieces about it,” he says. “But I don’t focus on that, because I’m making a film for an audience of more than one. Although when you are in the court of the Crimson King, obviously it feels like you are there to please the king, not his subjects.”

“I’ve spent three and a half, maybe four years, documenting both the experiences and the remains of people who’ve worked creatively with Robert. Many of them have said they’ve done the best work of their lives with him, but many of them have also spoken of the experience with a certain amount of regret if not bitterness. It’s not fun.”

After a generally glowing reception for In The Court Of The Crimson King since its release, Amies has been rattled by what he describes as one “slightly pissy” review that critiques the film for its cinematography, and this is clearly sitting with him: in the interview he makes frequent self-deprecating references to his camera skills.

“It’s kind of you to call it a style; I think of it more as a shambles,” he says, and “what I see on screen is basically a series of the least bad mistakes that I’ve made.”

“Listen, there are shots in there where the film is out of focus and it was because Robert had come to talk to me, and was standing too close, and the camera couldn’t cope and I was too frightened because it was too early on in the filmmaking process and I couldn’t go, ‘erm, Robert, could you just…’ can you imagine having that conversation with him?!”

“But if it’s any good, the audience is going to be listening to what they’re saying instead of wondering why it’s out of focus.”

“A big part of my creative process is going, this is fucking shit. Awful. terrible. But then you watch the thought process and you go, ok, so you know it’s shit. Why is it shit? And then you go through that process and once you know why it’s shit you can start asking how it would be better. It sounds very negative, but actually it’s quite useful.”

Moving from being in front of the camera to directing has been a protracted and incomplete learning process for Amies, from the days where he was working for Film4 interviewing at film festivals, where he says his interviews were basically, “So, David Cronenberg, what’s it like to be doing the thing that I want to be doing?” to the point at which he is making flawed-but-perfect films of considerable depth and insight.

But this drawn-out process of learning a craft is what the camera, the media, an article cannot capture, and this is as true for this filmmaker as for his musician subjects: Amies and King Crimson are, if united by anything, united by their constant quest for artistic perfection in an imperfect world.

“All the shitty bits about getting to be good, or at least getting to be effective as an artist, get condensed into one sentence: ‘struggled as an artist for several years,’” Amies says.

“That’s actually been 15 or 20 years of trying to figure out how to use a camera, or get your phone calls returned, or being humiliated and making an arse of yourself. All that gets condensed, because it’s the success at the end that everyone pays attention to.”

“But there’s a strong desire there to make something worthwhile in the process. To be struggling to make a piece of art about people struggling to make art is quite an illuminating experience.”

“King Crimson are not alone in grumbling about each other. I’m not letting out a big secret if I say that there’s often a lot of bitching backstage with bands. But when they play together, they absolutely nail it and to me, that’s really inspirational: that people can overcome all the other stuff and just go out and do an amazing job of playing music. That’s a fucking band.”

In The Court Of The Crimson King will screen at The Gate cinema on October 8 as part of IndieCork Film Festival at 6pm, with Q&A with director Toby Amies after the screening. Tickets at box office. More information on IndieCork here.