What to expect from the next Crawford Art Gallery

he Crawford is days away from closing for up to two years and change. The revamp is the biggest in its 300-year history. Kilian McCann looks ahead to what's to come for the storied gallery.

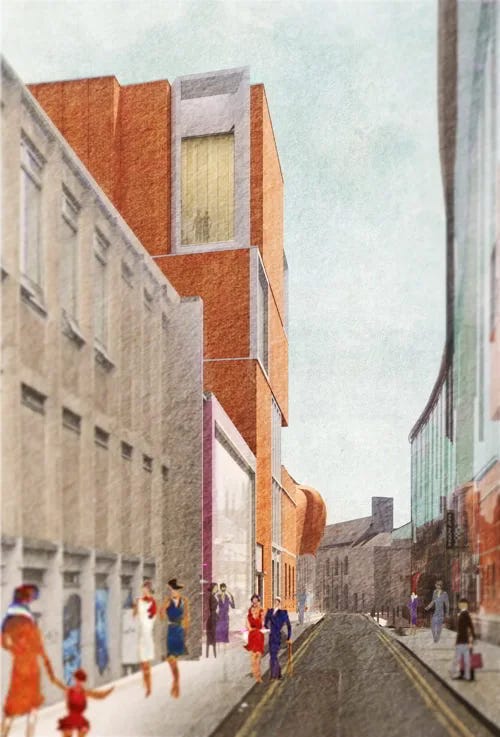

On Sunday, September 22, the Crawford Art Gallery will close as part of long-planned €29 million redevelopment. It’s not expected to re-open until sometime in 2027, when the revamped national gallery will be 50% bigger. It’ll also be a lot more noticeable with a new tower panned for the National Cultural Institution as part of the redesign from Grafton Architects and the OPW.

In 2019, roughly 265,000 visitors passed through the Crawford. That number plummeted during Covid, but by 2022 total visitor numbers were back up to 205,000. The Crawford is the biggest arts exhibition space in Cork, and one of the biggest in Munster, but visitors would be forgiven for thinking the gallery feels dated and disjointed. Much of its collection remains in storage, to be exhibited for only a few months of the year.

In November 2023, Grafton Architects unveiled the long-awaited designs for the gallery's planned extension. Originally submitted for planning in 2020 and resubmitted with revisions in 2023, the project centres around an impressive 8-floor tower. Once completed, the gallery will more than double its floor space. But what can we expect from this expansion, and will Cork finally have an art gallery to rival those in other European cities of its size

An important collection, mostly in storage

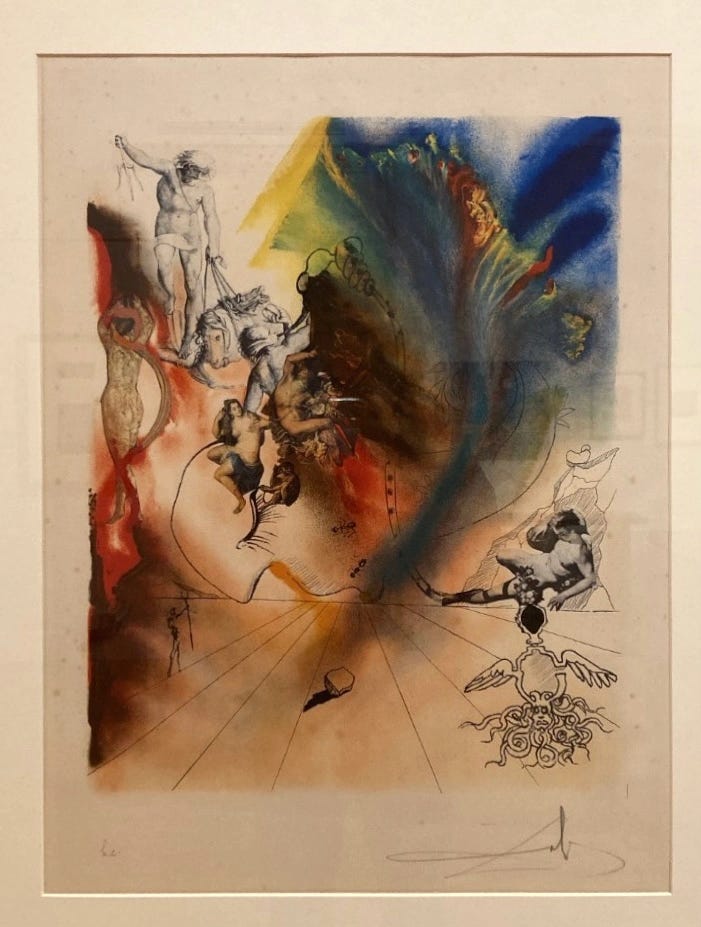

The Crawford currently houses around 3,500 artworks, which are nationally and locally significant, in ten different gallery spaces. The collection includes well-known works such as Seán Keating’s Men of the South, John Lavery’s The Red Rose and The Widow, and Daniel Macdonald’s The Eviction, which became known for being cleverly and controversially reworked by Mála Spíosraí. The collection houses some works by the important Irish artists Jack B. Yeats, Daniel Maclise, and James Barry, and surprisingly, the globally important Spanish artists Joan Miró, Salvador Dalí and Pablo Picasso. The Sculpture Gallery features pieces created under the supervision of Italian sculptor Antonio Canova, donated and sculptures by the legendary John Hogan.

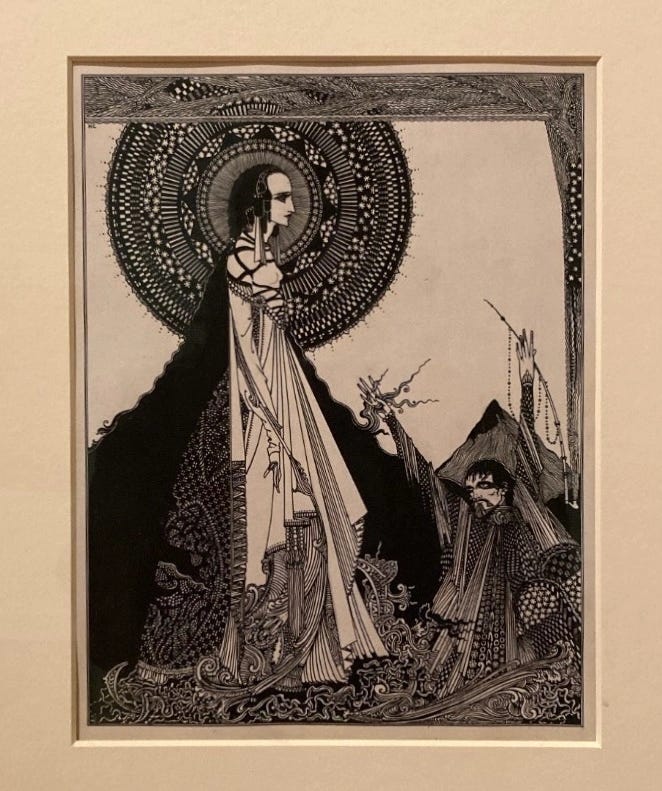

As well as three of his stained glass windows, which were removed at the end of 2023 and currently undergoing conservation, the gallery hosts a significant collection of watercolours and drawings by Harry Clarke, which are kept in storage for months on end. They are removed for a temporary exhibition once a year, for a few months at a time. The gallery recently also acquired its first Clarke piece in 99 years, a colour plate illustration called The Colloquy of Monos and Una.

This piece featured in the most recent exhibition of Clarke’s works, Harry Clarke: Bad Romance, which ran from December 2023 until February. It also displayed some of the draft watercolours for his windows, along with his drawings depicting Edgar Allen Poe’s short stories, as the gallery does at each of these exhibitions, and told the story of the Eve of St. Agnes, a John Keats poem, using Clarke’s watercolour plans for a stained-glass window which tells the story of this poem.

While these pieces feature in exhibitions every year, many pieces don’t. At the Harry Clarke exhibition from two years ago, Dalí’s work featured, at the same time that Le Vieux Bouffon by Picasso and Figure Walking by Miró featured at Radharc, downstairs.

The gallery also acquired 225 pieces from 39 new artists in 2021, and acquired 39 new artworks in 2022. However, the small and confined space available, both in the gallery and in storage, more than likely means that the gallery is constrained with what it can do with its collection and with its archives. It also means that when a temporary installation is installed, most notably with Corban Walker’s ‘As Far As I Can See’ in recent years, much of the gallery has to be moved around, with works returned to storage. This is something that curators in the extended Crawford will have more room to work with.

From artist Oral O’Byrne’s 2022 exhibition ‘Know That I Am Also At Sea’, (as well as ‘Site of Change: Evolution of a Building’,) you get the sense that the Crawford has many hidden and forgotten aspects which are being retraced, and that the richness and history of the building are being rediscovered which the new space could invoke. I looked at the plans, including the architectural design statement, the plans and elevations, and the landscape report, to understand what to expect from the new gallery.

An inviting space, open to the outside

Grafton Architects aims to create a warm and liberating space, improving orientation within the building, and increasing street presence on the three sides of the gallery. The biggest changes to the old building will be on the ground floor, where a new entrance and reception space will be created where the café currently sits. A new café will be built, fronted onto Half Moon Street, adding life to a street which could see an increase activity as the Green Room in the Opera House has been opening up more for gigs. The current main entrance will also remain, offering three separate access points and opening the gallery up to the outside.

A new garden will open onto Emmet Place, with the main part adjoining the reception, also linking with the other entrance. Its centrepiece will be the 300-year-old sycamore tree which stands near the current main entrance portico, with islands of flowers separated by paving, and a sculpture garden. The current garden has largely been an underused and forgotten space.

Between the reception and the café, a large, three-level atrium will cover a courtyard and provide easy access to gallery spaces. The older and newer sections will be linked with a stairway which will line the wall. Intended to be reminiscent of the city’s markets, it creates an area open to the outside. It will include a new bookshop (which will also front the old stair hall), stepped seating leading linking to new gallery spaces, and toilets.

What will the galleries look like?

In its current form, the gallery has five separate gallery spaces: The Sculpture Room is adjoined by The Lower Gallery on the ground floor, which along with the Upper Gallery, was designed by the Dutch architect Erick van Egeraat, and are known as the 21st Century Galleries. In the older section, The Atrium Gallery sits at the top of the grand staircase, leading to The Gibson Gallery and The Long Room, with the Penrose Rooms adjoining the Long Room. Up a small an unassuming set of stairs leads you to the Modern Galleries and the Harry Clarke Room.

Most of the existing gallery spaces and landmarks, such as the stair hall and the much beloved Sculpture Room, will remain as they are, accessed from the reception. The only changes be will the opening up of old windows towards the Sculpture Gallery from the Upper 21st Century Gallery, the reworking of space to expand the latter, the addition of some doors, and a new coffee shop where the current bookshop sits. In the older gallery spaces, new doors were to be opened up between the Long Room and the Penrose Gallery, but that was reversed in an amended application. Most of the new gallery spaces are being added on in the extension, or through a reworking of space inside the building.

On the first floor, a new gallery will sit above the café, linked with stepped seating to the courtyard below, with big glass windows facing onto Half Moon Street. There will be access to the Atrium Gallery and the Gibson Gallery via a walkway and new doors, also leading visitors into the upper 21st Century Gallery.

A stairway from the Atrium Gallery door will line the wall and lead to the second floor of the courtyard. On one end of the courtyard, new, repurposed parts of the old building will provide new gallery space. These new galleries open up the Modern Galleries wing, where Harry Clarke’s stained glass windows will be relocated and replaced with a multimedia room. The galleries and screening rooms will be moved around somewhat, and these spaces will be reworked.

A tower to top it off

At the other side of the second floor courtyard will be the main entrance to the new tower element of the gallery. This is the biggest and most imposing element of the new building, which will go up to eight floors. Intended as a “vessel for the imagination”, partially inspired by the red and grey of the Shandon Bells, it aims to stand out in the cityscape alongside the fly-tower of the Opera House. Designed to look like a lantern with views over the city, the architects aim for the building “to be read as a public building belonging to (Cork’s) family of church towers and belvederes.” A strong statement, but will it work?

Inside the tower, there is less than meets the eye. It’s bottom entrance, facing the second level of the courtyard, opposite the modern galleries, includes a Learn and Explore studio, where art education and engagement will take place. However, most of the tower floors, lying between this studio and the rooftop gallery, are closed to the public. These closed spaces are necessary, however, as they include two floors of collection storage and a collection interface studio.

The visitor climbs three flights of stairs, or takes a lift, to reach the next gallery space. Possibly a small bit indulgent, the rooftop space appears like it could be cut off from the wider gallery due to the distance and effort it would take to get this far. Once the visitor reaches the rooftop, they get a panorama of Shandon Bells and the northside, while another window offers a view eastward, toward the docks. Aimed as a belvedere, the space would provide a new, landmark space to pursue international collaborations and exhibitions. The top floor will be closed off to the public, providing essential plant space.

The tower, however, is an odd one. Time will tell whether it works with the rest of the gallery, or whether visitors will bypass it due to its distance from the main gallery areas. Time will also tell whether it will end up being considered an eyesore, not unlike some of additions and changes made by neighbouring buildings. However, the panorama it will provide of the city, with Shandon Bells and the future docklands within its sightline, will more than likely make it a powerful space in which to exhibit. The view might even compensate for exhibitions that don’t add up to the sum of their parts.

The Crawford in four artworks and public installations

Wedgework by American superstar James Turrell was both a revelation and an incredibly disconcerting experience. Created while Turrell had a residency in the Cobh Yacht Club in the mid-nineties (art works in mysterious ways) it was installed in the upper reaches of the old gallery. “Wedgework at the Crawford invites the viewer to enter an illusory space where boundaries are dissolved and ambiguously resolved with light,” wrote Nuala Fenton in a review. She wasn’t wrong. Bring it back.

The public toilets. Modernist elaborate masterpieces. Free to use. Beautifully lit. Clean. We will miss them so.

Men of the South. Is it the Crawford’s most famous artwork? Take away the guns and Keating’s large scale painting could be an ode to pastoral Ireland. The men are handsome, rugged, serious.

The Widow. John Lavery’s portrait of Muriel Murphy MacSwiney is powerful for what it reveals and hides. The wife of Terence MacSwiney, Sinn Féin Lord Mayor of Cork, Murphy MacSwiney burst on to the world stage following her husband’s tragic death by hunger strike. Lavery casts Murphy MacSwiney as an apparition, a ghost, shrouded in sadness, but defiant.

Meet the owner of Cork's newest gallery

·At the top of Shandon Street, a new sign has popped up outside the tiny laneway that once housed a chaotic secondhand furniture shop known as Trotter’s.