Vera's Battle: Not Over by a Long Shot

When the Irish government started delivering medical cannabis to Irish patients during Covid-19 restrictions, Cork mother Vera Twomey thought her six-year battle was over. But it's not.

“Ava Barry went back to school yesterday.”

There’s a very endearing habit that Cork mammies have, of calling their children by their full names. It happens when you’re in trouble, or it happens when they’re particularly proud.

And Vera Twomey’s voice has a little tremor of pride in it as she describes her eldest daughter Ava, 11, returning to school.

“Oh my days, she went back yesterday and it was like watching a weight being lifted from her,” Vera says. “She had fun, and she was exhausted when she came home. I don’t know how to express it effectively, but I can see the light come back into her again.”

It sounds like a common enough parenting experience, but for Vera and her husband Paul Barry, it’s anything but.

Ava, like many children with special needs, has had a tough time with the Covid-19 restrictions, missing friends and teachers. Her health suffered towards the end of last year, but despite that, she’s still in a far better place than she was six years ago. Her condition is manageable now.

You might be familiar with elements of Ava’s story, because for a while, her mum was in the news a lot. But even though she isn’t right now, their story is far from over.

Ava was born with Dravet’s Syndrome, a catastrophic form of epilepsy. Throughout her early years, she suffered relentless seizures and hospitalisations. Twice, little Ava suffered heart failure due to the severity of her seizures; brain damage incurred in those early years have left her with permanent difficulties with speech and other functions.

As a baby, Ava was prescribed epilepsy drugs including phenobarbital, an anti-convulsant in the barbiturate class, and benzodiazepine, notorious for its abuse as a highly addictive illegal drug, to prevent her seizures. Not only did they not work, but they came with extreme side effects, an additional burden to her condition. And they didn’t work. No matter what combination of drugs she was put on, her seizures continued.

Up to 20% of Dravet Syndrome sufferers die in childhood. Vera and Paul, who live in Aghabullogue near Macroom, were given a sickening prognosis by doctors: she would never walk or talk, and she may not survive to see her third birthday.

Every parent’s worst nightmare, then, and Ava’s early struggle for survival has Vera apologising for getting emotional on the phone.

“She’s just an extraordinary person,” Vera tells me. “She’s beaten all the odds, and she’s fought and fought to stay with us. In the early years, there were times when the doctors had given up on her. But we never gave up on her, and she never gave up, and that’s the most important thing.

“Even as a tiny girl, she had a ferocious will to survive. I’m really so proud of her. Ava is a gift, and it’s a privilege for me, as her mother, to go out and get what she needs.”

For Vera, going out and getting what Ava needs has meant feats of endurance and willpower beyond what many of us can imagine, a lengthy saga unfolding over many years. Because what Ava needs is medical cannabis. This, in light of the fact that she hasn’t had an emergency hospitalisation since Vera and Paul first decided to seek their own approach and start treating her with cannabis in 2016, is inarguable.

Ava now takes a combination of CBD (cannabidiol) and THC (Tetrahydrocannabinol) in a medication called Bedrocan, which is produced in The Netherlands. While CBD products, which lack the psychoactive THC - the active compound that leads to a “high” - can be of benefit, some of the benefits are not isolatable from THC.

And Vera believes this is a large part of the political hesitancy, the societal reason why she has been subjected to an extraordinary saga of heel-dragging throughout the years that she has been trying to gain equitable access to the medicine that is so vital for her daughter.

Fears that the introduction of medical cannabis will act as the proverbial gateway drug to the legalisation of cannabis for recreational use abound and have been expressed by certain high-ranking Irish medics.

“It’s one of the most significant factors,” Vera says. “There’s a reticence and a resistance and a fear about cannabis as a medication in this country.”

A recap of the story so far:

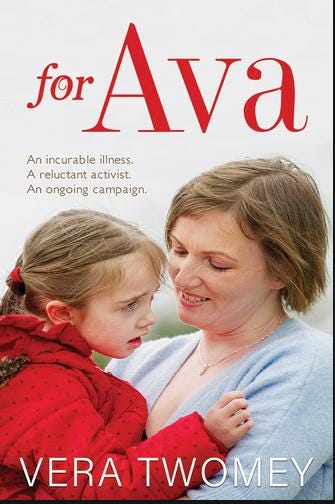

When I last spoke to Vera in 2019, she had just published her self-penned autobiographical account of the family’s struggle, “For Ava”. Taking on the challenge of writing a book, although a large undertaking for Vera, who has three children younger than Ava, is nothing to the time she set off to walk from her home to Leinster House in Dublin, to protest the government’s medical cannabis policy. To write the entire story in full is indeed the subject of a book, so here’s a timeline of some of the events surrounding the campaign for medical cannabis:

October 2013: Luke “Ming” Flanagan launches his ill-fated Cannabis Regulation Bill, which sought to legalise both recreational and medical use of the plant.

November 2016: After Ava has a particularly bad seizure, Vera sets off to walk the 260km from her home to Leinster house to highlight that she can’t get the combination CBD/THC treatment that Ava needs. Nine hours into her walk, with heavy media interest and social media activity, Health Minister Simon Harris contacted Vera to urge her to stop her walk and to arrange a meeting.

December 2016: Gino Kenny’s medical cannabis bill is passed with no opposition in the Dáil.

January 2017: Vera confronts Simon Harris at the opening of a Cork hospital and accuses him of betraying her trust over delays; Harris says the HPRA (medicines regulation authority) are conducting a review of medicinal cannabis that will be completed soon.

February 2017: Vera sets off to walk to Dublin for a second time.

March 2017: Vera arrives at Leinster House, having used crutches and a wheelchair to complete her journey. She sleeps outside for one night and is removed by Gardaí on the second day after Simon Harris refuses to meet her.

April 2017: Vera is stopped at Dublin airport by customs officials with sniffer dogs while returning from Barcelona with CBD-based medicine she had bought for Ava.

June 2017: Vera takes Ava to The Netherlands to begin combined CBD/THC treatment. She responds excellently.

July 2017: The Oireachtas Health Committee rejects Gino Kenny’s medical cannabis bill, saying it’s not a “safe course of action” and could lead to decriminalisation.

November 2017: Simon Harris signs an individual licence for Ava to access her medicine; Vera and Paul still need to fly to The Netherlands every three months to purchase her Bedrocan prescription.

April 2018: Vera accepts a People of the Year award televised on RTE. She uses her speech to confront Taoiseach Leo Varadkar, sitting uncomfortably in the audience, and demand that he legislate for medical cannabis. RTE’s YouTube channel carries an edited clip but her full speech is here.

June 2019: Simon Harris signs into legislation the Medical Cannabis Access Programme (MCAP).

August 2019: Vera releases her self-penned book, “For Ava”.

April 2020: A temporary delivery system to ensure patients don’t have to fly for their medicine during Covid-19 restrictions is announced.

December 2020: Vera attends a Zoom meeting with Minister Stephen Donnelly, who confirms that delivery arrangements for medicinal cannabis licensees will become permanent.

January 2021: Stephen Donnelly announces funding for the MCAP under the HSE Service Plan for prescriptions for medical cannabis for a limited range of conditions. But not for Bedrocan.

The best Christmas ever

Following years of campaigning, outlined in detail above, Covid-19 provided a blessed Trojan Horse for Ireland’s 58 medical cannabis licensees, and seemed for a brief, tantalising time, to spell light at the end of the tunnel for Vera.

When Covid-19 hit, patients who had been forced to travel to The Netherlands to fill their prescriptions, a process Vera describes as “exhausting and stressful” and detrimental to family life, could no longer safely do so.

The Department of Health made temporary arrangements for the delivery of these medicines.

In December 2020, Vera attended a Zoom meeting with Health Minister Stephen Donnelly at which he confirmed that the arrangement would now become permanent: for the first time, medical cannabis importation was on the cards.

“It was the best Christmas ever,” Vera says. “I’ll always support cannabis in this country because it’s a magnificent medication and I’m happy to talk about it, but I thought in December that we’d reached the stage where if anyone wanted to talk to me, they could, but that there wasn’t another obstacle to overcome.”

Then, something truly baffling….

A month later, the Medical Cannabis Access Programme (MCAP), signed by Donnelly’s predecessor Simon Harris, came into being, and some medical cannabis products would now also be funded under the HSE service plan.

BUT NOT AVA’S MEDICINE.

Products from two Canadian companies, Tilray and Aurora, are included in the MCAP, as is one Australian CBD-only product. But Bedrocan, which is used by the majority of Irish licensees, and is even the only cannabis medicine named on the Department of Health’s “Applying to the Minister for a medical cannabis licence” document.

No one at the Department of Health has explained the reasons for this to Vera. I contacted the Department through their press office and my email had yet to be acknowledged by the time we went to print with this.

“How they could have overlooked the actual majority of patients in this country?” Vera asks me. “It’s mystifying to me, is it mystifying to you?”

Right now, Vera and Paul have to have €9,500 in the bank every three months. They must make an upfront payment for Ava’s medicine, and then they must wait four to five weeks to be reimbursed. “Then the money is in cold storage for the next time,” Vera says.

This might sound like child’s play compared to having to fly to The Netherlands, but it’s still stressful: it’s a large sum of money, and reimbursement is not guaranteed. For Vera, it’s also become a matter of equity.

“From 2010 to 2016, when Ava was on pharmaeuticals, we were on the Long Term Illness scheme,” she says. “You have your Long Term Illness book, you go to your pharmacy and collect your medication and off you go. And we were years on pharmaceutical medications, and none of them worked. All of that money – all her medication and her hospital admissions, four or five months each year in hospital. All that money is saved. It’s ridiculous to be treating cannabis the way it’s being treated.”

“I’ll do whatever needs to be done to bring this to a position where her medication is treated the same as any other epilepsy medication. If there’s a deviation in how her medication is treated, funded, compared to other epilepsy medications, that’s a disrespect to my child and I won’t allow it.”

Communication with the Department of Health is poor.

“In the past couple of days, Stephen Donnelly’s office have made contact with me and stated that they are ‘looking into the issue,’” Vera says. “Before that phone conversation, I had received an email on March 28, saying they were looking into the issue. I don’t have any information about who is responsible in this current situation with the Bedrocan, which is very frustrating.”

“It took me six months of daily social media activity to garner a meeting with Stephen Donnelly.”

In a previous email to Cannavist, the Department of Health said that the MCAP fund required the medical cannabis manufacturers to approach them for inclusion.

I contacted Bedrocan, and they told me:

“Bedrocan is a contract manufacturer for the Dutch Government. Within the Ministry of Health, we have the Office of Medicinal cannabis, who order raw material from our company, Bedrocan. The Office of Medicinal Cannabis is the official producer of the final products. For that reason, there is no contact between Bedrocan or any off takers or authorities in other countries. This is a matter of the OMC.”

Regardless, as Vera points out, if the Dutch OMC have issues with export, the Bedrocan is arriving on Irish shores now.

”So it’s a matter of funding and that isn’t to do with the Dutch government, is it?” she asks. “It’s the Irish government’s funding arrangement.”

On the road again?

Twice, Vera has set off from her home to walk to Dublin for change. So it seems natural to ask: if Stephen Donnelly won’t close out the deal and ensure Ava’s essential medicine is included on an equal footing with any other epilepsy treatment, will Vera be willing to set off on the long walk again?

“I’m willing to sacrifice myself to get what my daughter deserves,” she says, with the familiar note of steely determination in her voice. “We walked to Dublin once. Without my realising it for a long time after, that walk alerted thousands of people to Ava’s plight. I don’t want to be civilly disobedient, I don’t want drama or to fight with anybody. I am aching to co-operate, for a resolution. But if they push me to a point that I can see there won’t be a satisfactory resolution, I would not rule that out. I mean that.”

“That wouldn’t be a joke to me. If that’s what needed to be done to fix this, I would suffer the short-term consequences for my daughter.”