Two 15th Century manuscripts written in Cork, side-by-side in The Glucksman

Filleadh na nDeoraithe/The Return of the Exiles showcases two manuscripts that contain the multitudes from Irish translations of Marco Polo’s journey East to 'armchair wanderings' writes Ken Ó Donnchú

Over the next nine weeks, The Glucksman in University College Cork will display two priceless Irish manuscripts, side by side, for the only time in their history. These treasure-troves of Irish literature were written in different parts of Cork, in the Irish language, towards the close of the fifteenth century. In the years that followed, both were taken out of Ireland. One has since been returned, while the other is on a short visit home.

The Book of Lismore (written between 1478–1506) and Rennes Manuscript 598 (written around 1476) provide a fascinating insight into the native intellectual culture of fifteenth century Ireland, when the overwhelming part of the island was Irish-speaking. Taken together, Lismore and Rennes (not their real names!) illustrate the diversity of texts produced by the Irish learned classes, those families – among the educated few – who functioned as historians, poets, chroniclers, translators and scribes.

The names given to manuscripts often changed over time according to where and in whose possession they were. These two manuscripts are good examples of this phenomenon: the Book of Lismore was actually written in Kilbrittain, near Kinsale, while Rennes 598 was written in Kilcrea, west of Ballincollig. Their subsequent histories – one was transported to Waterford (and then England), the other to Brittany – account for their modern titles.

The Book of Lismore was written for Fínghean Mac Carthaigh Riabhach, Lord of Cairbre between 1478 and 1505. Fínghean’s stronghold was Kilbrittain Castle. A note in the manuscript tells us that it was written for him by a certain Aonghus Ó Callanáin. Aonghus wasn’t the sole scribe, but the only one whose name is recorded in what survives of the book (loss of leaves, common in manuscripts, has occurred here).

Manuscripts written in Ireland during this period were often patronised. Just as the Medici sponsored art in contemporary Florence, so powerful families in Gaelic Ireland sponsored the production of manuscripts, which, like the Book of Lismore, were significant cultural monuments and indicators of prestige.

By contrast, if Rennes 598 had a patron, we don’t know who (s)he was. We do know, however, that the manuscript was to be found at Kilcrea on Déardaoin Mandála (Holy Thursday) in 1476. Thanks to new research by Andrea Palandri, we also know the name of its scribe – Tadhg Ua Ríoghbhardáin (Tadhg Ó Ríordáin in current spelling), a most productive scribe in his day, but unlikely to have been a Corkman.

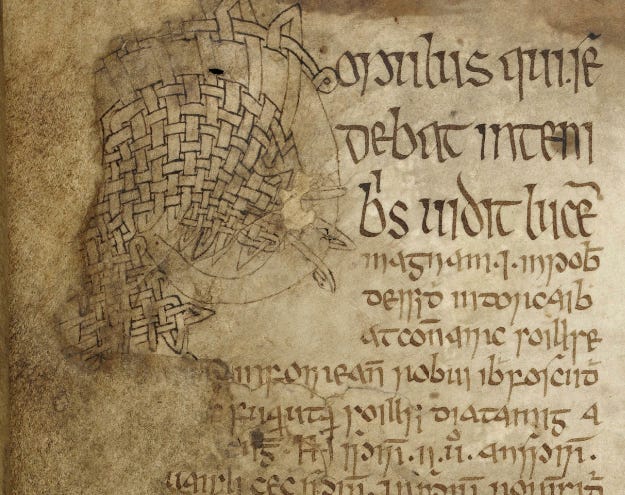

In their specific contents, Lismore and Rennes notably contrast, but there are many other points of comparison between them. Both are Cork productions, their leaves (or folia) are made of vellum (or calfskin) and not paper, and their style of writing is the beautiful insular miniscule, which will remind readers of an older vintage of the cló Gaelach of their schoolbooks. These manuscripts belong to the end of what one famous scholar called a period of ‘literary revival’ between 1350–1500, when books of huge dimensions, like the Book of Uí Mhaine, the Book of Ballymote and the Leabhar Breac were produced. There aim was ‘to recreate Ireland as it was in the past, and as it should be in the present if certain events had never happened’. Keeping this in mind, we can see why so many of the texts these manuscripts contain had no immediately obvious relevance to their time of writing – but scratch the surface a little, and political messages are sometimes there to be deciphered!

So, what kind of texts do they contain? A crude division of their contents can be drawn between secular and religious texts, bearing in mind that all Irish language literature has been transmitted through the prism of Christianity, and that writing as we know it first reached this island with religion. Still, let’s stick with this division, and start with the religious content.

The first quarter of the Book of Lismore tells of the lives of famous Irish saints, including Pádraig, Colm Cille and Bríd. It also contains other kinds of religiously-themed texts: Gabháltais Shéarluis Mhóir (The Conquests of Charlemagne) is an important crusade narrative. The single text which Rennes 598 and the Book of Lismore both contain is An Teanga Bhiothnua (The Evernew Tongue), an exotically imaginative account of the entire universe, and where God fits into it.

Other religious texts in Rennes 598 include the Irish translation of De Contemptu Mundi (On Contempt for the World) a text about asceticism, or strict self-discipline for religious reasons. Rennes 598 contains the only surviving copy of the Life of Saint Colmán mac Lúacháin. Colmán’s biography is a far cry from the Christian doctrine of De Contemptu Mundi, but typical of the Irish hagiographical tradition, where saints appear as all-conquering and all-converting, never shying from combat, and capable of an array of miracles.

Less exotic, more secular, but also of a fantastic nature are the travelogues found in both manuscripts. Lismore contains the only copy of the Irish translation of Marco Polo’s famous account of his journey East (he reached Beijing in 1274). Political allegories were mentioned above – Andrea Palandri has recently claimed that the Irish translator of Marco Polo rewrote a particular episode in his translation to reflect infighting between Fínghean Mac Carthaigh Riabhach and his unfortunate cousin Cormac (who was captured and castrated in 1478).

Rennes 598 has a copy of the Irish translation of the Book of Sir John Mandeville. Composed in French, these so-called ‘armchair wanderings’ (its author, à la Emily Dickinson, never left home, it seems) were among the most popular works of the period throughout Europe. The copy in the Rennes maunscript was translated in west Cork by Fínghean Ó Mathghamhna in 1475, from ‘English, Latin, Greek and Hebrew’, a fanciful but nonetheless admirable claim.

Dindshenchas material – the history (senchas) of the ‘notable places’ (dinda) of Ireland – is found in Rennes 598, including an account of the famous Teamhair or Hill of Tara, along with other noteworthy dinda such as Beann Éadair (Howth), Port Láirge (Waterford) and Carn Uí Néid (Mizen Head).

Lismore contains a different genre of text with all-island significance. This is the Fiannaíocht lore of Fionn mac Cumhaill and his fian warriors. The expansive Agallamh na Seanórach (The Colloquy of the Ancients), in which Fionn and the fian’s mighty deeds are recounted to St. Patrick by the age-defying Oisín and Caoilte, is one of the manuscript’s most celebrated texts. Less renowned, but profoundly intriguing, is its copy of Tromdhámh Ghuaire (Guaire’s Burdensome Company), a satirical tale which ultimately pits the boundlessly-generous King Guaire against the mercilessly-greedy poet bands who seek his hospitality.

By now, your head is spinning from this frenzied account, and we haven’t covered the half of what they contain! I won’t dwell on their histories – despite containing many chasms, these are almost a match for the manuscripts’ contents. To learn more of what happened to them after their creation in fifteenth century Cork, get along to The Glucksman before November 5. This is a unique chance to view these priceless artefacts, which bear witness to the breadth of Irish literary production, its European communion, its artistry (we haven’t even discussed illumination and decoration!) and the violent political intrigue sometimes lurking behind the written word.

Filleadh na nDeoraithe / The Return of the Exiles runs until November 5 in The Glucksman Gallery in UCC. More details here.

Dr Ken Ó Donnchú is a lecturer at the Department of Modern Irish at UCC.

Theatre review: Katty Barry - Queen of The Coal Quay

If ‘Katty Barry - Queen of The Coal Quay’ is anything to go by, then the eponymous protagonist was the very living embodiment of that wondrous Cork profession: she was a good old fashioned rebel. Having passed away in 1982, her boisterous and often tumultu…

Superb writing style. Imagine walking into a University lecture and getting a lecture like that. It would give you goose pimples.

Ah that's a nice read thank you Doctor.