The octopus that nearly strangled Cork

A new documentary by architect and poet Michelle Delea tells the extraordinary tale of City Seventy, the group of campaigners that stopped Cork City Centre from becoming a giant flyover and carpark.

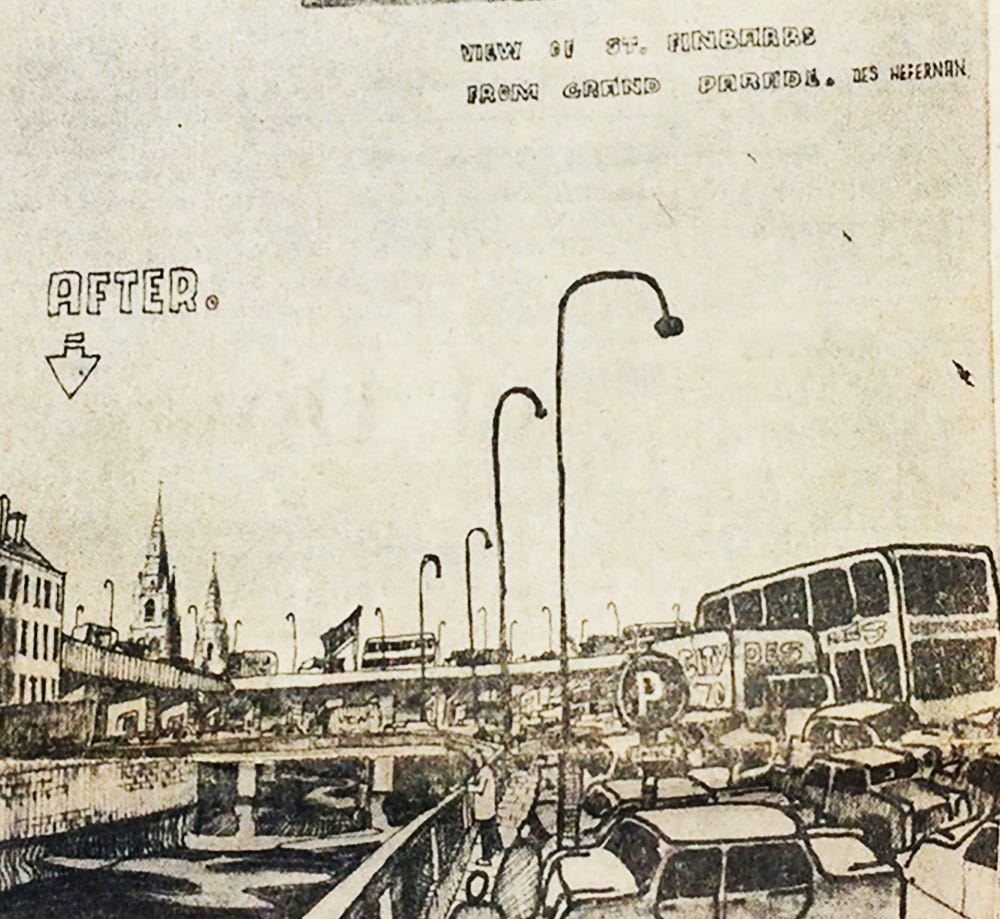

Michelle Delea stands on a footbridge over the Lee, good-naturedly posing for a photograph. Behind her, a view so familiar to Corkonians: the spires of St Fin Barre’s Cathedral, behind the elegant stone arches of the South Gate Bridge.

In a parallel universe, one in which a group of seven young men didn’t band together and call themselves City Seventy, or perhaps one in which there had been no architecture course put on at the Crawford School of Art and Design, Michelle probably wouldn’t be able to stand where she’s standing: it would be a snarl of traffic and a large car park, and nothing more.

“A chilling picture of a blitzed and ravaged city”

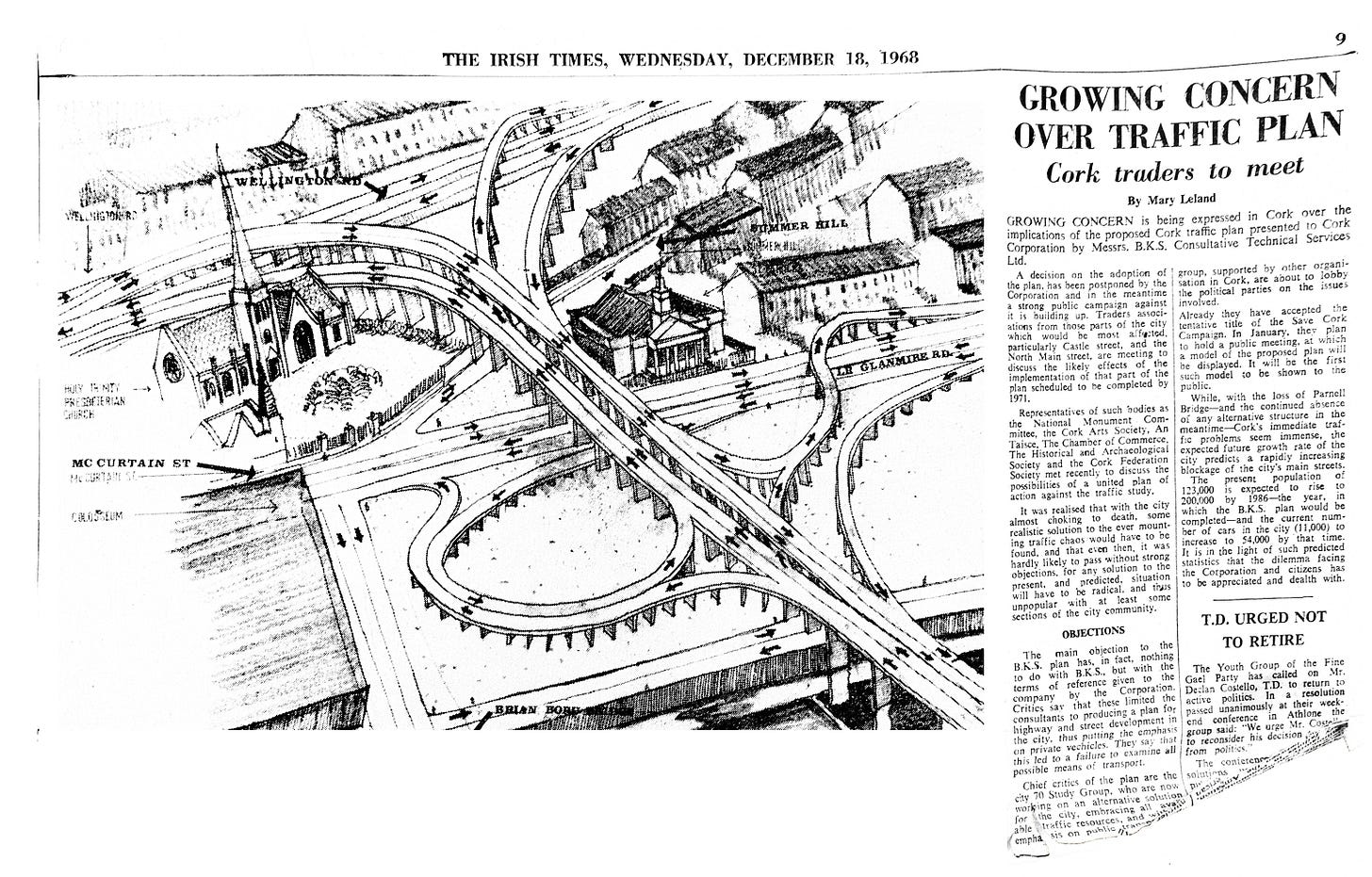

In 1968, the BKS Traffic Plan proposed an elevated ring road and set of spaghetti junctions for Cork City Centre. The idea was full city access for personal motor cars and it was seen as a progressive and liberating notion; indeed, city councillors were highly enamoured of the plan and voted it through.

Emmet Place would be a four lane highway, Cornmarket a three lane, one-way road. Cork’s landmarks would be completely dominated by elevated roads and massive concrete piles.

Journalist Mary Leland, writing in the Irish Times, described the plan as “the sprawling octopus of an elevated highway.”

90 acres of car parks

On top of the network of elevated roads, the plan also required 90 acres of car parks; to achieve this, entire city blocks and the buildings of some of Cork’s most distinctive and historic quaysides, including French’s Quay, Sullivan’s Quay and George’s Quay, would be levelled en masse.

“The one I always come back to, which I can’t fathom, was that they were going to demolish the whole block going from Paul Street down Cornmarket, up the Quay and down Half Moon Street,” Michelle Delea says. “That’s now very much the heart of the city. That was going to be flattened for car parking, and it’s one of many blocks that were designated for clearance.”

Michelle is the director of a new documentary, titled The Sprawling Octopus of an Elevated Highway, which tells the extraordinary tale of that ill-fated BKS plan, a group of seven courageous young architects, an equally courageous journalist, and the drawings that saved Cork city.

A Cork Centre for Architectural Education (CCAE) graduate and a regular on Cork’s poetry scene, Michelle had not worked in film before producing this 35 minute documentary, an impressive debut, although she did study a film module in her final year of college in 2020.

Michelle is from Patrick’s Hill and now works full-time in architecture; she first heard the story of the BKS plan when the group of architects that called that managed to stop the plan in its tracks came in to CCAE to give a talk on this fascinating history.

Gerard O’Callaghan, Harry Wallace, John Heffernan, Gerald McCarthy, John Santry, Des Heffernan and Neil Hegarty were young graduates of the Crawford Art School’s first ever Architecture degree class when, aghast at the potential of the BKS plan to carve up Cork, they founded City Seventy and began holding public meetings and proposing alternatives to the looming car dependency.

Their vision for Cork has deep resonance for today. They were talking about pedestrianisation, public transport networks, a liveable city filled with plazas and social spaces.

Drawing saves Cork City

By all accounts, drawings by one of the group, Des Heffernan, were instrumental in the success of the City Seventy campaign, in getting people to understand the extent to which the planned roads would destroy the city.

Because, hard as this may seem to believe, Cork City Councillors had approve the BKS plan without seeing any visual representation of what it would look like.

They produced a booklet to distribute, and when Mary Leland covered the story for the Irish Times, her words were accompanied by Des’ drawings.

“A lot of the councillors who had been for the plan turned against it once they did see the drawings,” Michelle says. “But I suppose that’s the skill architects have: they knew exactly what it would look like themselves, but they had to go through the process of drawing it for communication purposes. I think it really highlights how important it is to have a local school of architecture, too, because they had the care to invest; when they came across this plan, they could immediately visualise what this was.”

For Michelle’s documentary, new CAD graphics were produced to give a sense of what the highways would be like: you can see one in this article.

History repeating: a parallel with the Love The Lee campaign?

All’s well that ends well: they didn’t pave paradise or put up a parking lot. Although approved, the BKS plan never materialised. A new city manager, Joe McHugh, who had also seen the City Seventy drawings, was not a fan of the proposed roads. The plan was quietly shelved.

The documentary is the story of a group of professionals coming together to stop the council from undertaking a vast infrastructural project that they say will permanently damage the cityscape: in that sense, is there a parallel with the Save Cork City/Love The Lee campaign?

“It’s hard to watch the documentary or hear the story without thinking of that,” Michelle says. “We haven’t explicitly referred to it, because it’s a very politically charged topic. But people’s beliefs and minds will go where they will.”

“Cork could really go in one of two directions at this point, and it’s a really important time to think about these things: I really wanted the film to get the city to question its own autonomy and maybe even give local activists a sense of resurgence.”

“Really, to remind people that at the heart of it, the city is for people to live in and spend time in. So I hope the film feeds the conversation a new perspective.”

The generation game

In The Sprawling Octopus of an Elevated Highway, there’s something very moving about the seven architects meeting today to reminisce about their activism, 50 years after the fact: a council of elders of sorts, they meet in the library of the Crawford Art Gallery, which was the art school in their time, and where they studied together.

“I wonder do people think they deserve to love the place that they live, or is it just that we’ve lived here so long that we love it?” Mary Leland jokingly says to Des Heffernan.

“Introducing that idea of interacting between different generations really underpinned the film,” Michelle says. “It’s something I’m very familiar with from poetry: I go to the Ó Bhéal poetry evenings in the Long Valley, and you can literally have anyone from 18 to 95 decide to get up and say what they need to say. That’s really rewarding. Introduce cross-generational ideas and everything always get a bit more human.”

Michelle herself has been attending Ó Bhéal and writing poetry since she was in her teens.

Now that she’s made a first documentary, is she likely to make any more?

“I’ve been comparing film-making to getting a tattoo,” she says. “I don’t have any, myself, but I imagine it can be a bit traumatising while it’s happening, but then you can’t wait to get another one.”

“I’m not even finished the full process with this film, but I can’t wait to do another one. There will be more films coming from me, I think.”

The Sprawling Octopus of an Elevated Highway (2022) will premiere in the Crawford Art Gallery on Culture Night, Friday September 23. A 6pm screening with Q+A is sold out, but there are screenings at 7.30pm, 8.30pm and 9.30pm. Book here.

Thank goodness for the City Seventy!