The long life and slow death of the St. Patrick's Street 'Hut'

For close on 100 years, a small kiosk at the top of St. Patrick's Street loomed large over the lives of firefighters, tram workers and bus drivers. Now, it's being left to rot.

Lately I’ve been digging around the Anthony Barry treasure trove of photos. The archive contains thousands of photos of the life and times of Cork - many of the pictures were taken in 1960s and 1970s - and sometimes when I am weary from work and social media and bleary-eyed from it all, I’ll click over to the former Lord Mayor’s collection of photos and browse around.

Maybe it’s the black and whiteness of it all, or the way that little things stood out, or the leisurely pace of life in the city, a city that had tram lines and rail lines and bicycles galore. Of course, the lens in which we look at these pictures matters too. Nostalgia matters, even if it doesn’t.

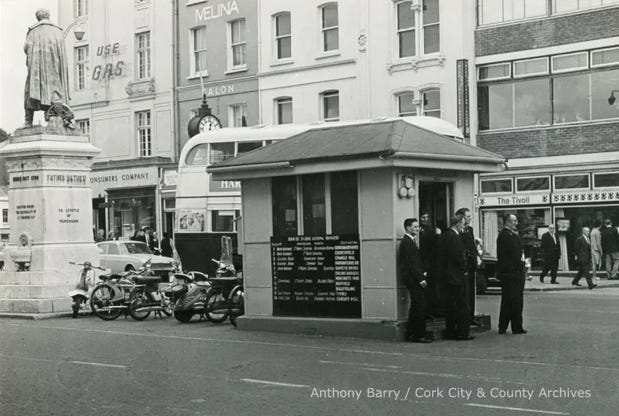

One of the shots I came across recently is taken near the top of St. Patrick’s Street from somewhere around where Easons bookshop is located. Fr Matthew has his back to the camera; from his plinth he looks across the north channel of the Lee, and there’s a long rectangular flower bed beneath and in front of him. There’s a double-decker bus with an ad for Guinness coming down the street passing under Mangan’s clock. But the main building in that shot is the one that I was hunting for, both online and in real life.

It’s not much of a building at all, and certainly not one that most people in Cork have ever set foot inside. But over time, a long time, it became part of the fabric both of St. Patrick’s Street, but also of how we talk about Cork. I’m talking about the ‘hut’ behind Fr. Matthew - it’s also known as the ‘Fireman’s Rest’ and tongue-in-cheek as the ‘Bungalow - and it was swept away in the new millennium plan that flattened the history of that once interesting street.

John Pearson is one of the men, and it’s nearly all men, who knows the confines of the ‘hut’ well. He knew the building long before he ever set foot in it, as he grew up on Winthrop Street, just down from the ‘hut’, and well before McDonald’s arrived on that street.

“If the wind was blowing in the right direction, you could hear the traffic inspector blowing his whistle to start the last buses on their journey,” John recalls. As a young fellow, aged 8 or 9, he would stick his head out the window craning it towards Cudmore’s to catch the cavalcade of buses moving off for their final journey of the night.

The ‘hut’ at the Statue was the anchor for buses converging in the city on St Patrick’s Street (John likens the ‘hut’ to a nerve centre). It also acted much like a water cooler before such a thing existed. Bus drivers and conductors and inspectors and messenger boys and bosses and anyone connected to CIÉ would invariably be drawn to it and into it at all stages throughout the day. You couldn’t have positioned it to be in a better spot. At the top of the street, straddling the thoroughfare perched between a constant line of buses heading north and south, ploughing in early and taking off late, to all points in the city.

A brief history of the hut

The ‘hut’ lived on St. Patrick’s Street for close on a hundred years. It was moved on in 2002 when the street was refurbished as part of the €13 million project that was heralded in some press reports as “bringing Barcelona socialism to Cork.” (Beth Gali, the architect who won an international competition to redesign the street, is from Catalonia, hence the Barcelona reference. The socialism part of that reference is a bit of a leap).

The hut has a charmingly complex and (mostly) co-operative history. It’s been used and shared by workers from Cork Electric Tramways and Lighting Company, the city’s fire fighters and then by workers from CIÉ, who passed it on to Bus Éireann who used it right up until it was removed in 2002.

As Pat Poland, a retired fire fighter and historian, outlines in his wonderful books For Whom the Bells Tolled: A History of Cork Fire Services 1622 – 1900 and The Old Brigade: The Rebel City’s Firefighting Story 1900 – 1950, the ‘Firemen’s Rest’ (which eventually became the bus driver’s ‘hut’) was first placed at the junction of Grand Parade and Great George’s Street (which is now Washington Street). The ‘Rest’ was made in Glasgow in 1892, and when it was installed in Cork it had the distinction of having one of the few functioning telephones in the city. It was built on a budget of £60.

Its purpose, as the name implies, was as a rest or shelter for on-duty firemen. As Pat explains:

While on duty, the fireman is on no account to leave his station. The watch-box is provided as a protection against inclement weather and must not be used by any other person. The door must not be closed when the fireman is within, as he is expected to be vigilantly zealous for the preservation of life and ready to give immediate attendance whenever required.

Writing about the ‘Rest’ in 1894 in the journal Fire and Water, Alfred J. Hutson, the city’s fire chief and a transplant from London, described it as “one of the most comfortable outstations in the Kingdom.”

Timothy Ahern, a fireman, who spent many a night on duty in the Rest, had a very different opinion. He described it as one the worst stations in the city; the iron walls sweated with condensation and furthermore the on-duty firefighter had to put up with having the door open all night. Ahern, who requested a change in roster, said he had been on “night-duty at the ‘Rest’ without a break for a period of one year and eight months.”

Somewhere in the middle of Hutson’s hyperbole and Ahern’s exasperation perhaps lies the truth.

The ‘Rest’ moved around a bit before it ended up with a permanent home behind Fr. Matthew. Not long after it landed on Grand Parade in May of 1892 a director of Alexander Grant’s department store said it obstructed views of the shop, and he petitioned to have it shifted. It was agreed that the ‘Rest’ would be moved 20 feet down the street towards the south channel, but local residents, countered, objecting they didn’t want it obstructing them or the view and the saga (NIMBYism before it had a name) dragged on for a year, before the city fathers and fire fighters shifted the rest up to Lavitt’s Quay.

And so in 1894, the ‘Rest’ was moved close to the Opera House nearer the Lee, and stayed there until once more it was moved to a place of prominence on St. Patrick’s Street.

For a few years until it was moved to the Statue firefighters had a gentleman’s agreement with the tramway company that they could use their ticket office by night; the mobile escape was left resting up against the statue of Fr. Matthew. In the morning, the ‘wheeled escape’, essentially a ladder mounted on large wheels - there were half a dozen of these placed around the city in the late 19th century - was returned to the ‘Rest’ at Lavitt’s Quay, and the ticket hut was taken over by the tram company. This arrangement continued for a few years into the early 1900s until a new deal was worked out between the tram company and the firefighters.

As Pat writes:

the ‘Fireman’s Rest’ and escape were moved from Lavitt’s Quay to St Patrick’s Street where the ‘Rest’ permanently supplanted the small ticket office. Electric lighting and a telephone were installed, and, from then on, barring a period during the Troubles of 1920 –’22 (when the city centre escapes were relocated) until 1930, the ‘Fireman’s Rest’ was used by the tramway personnel by day and the fire brigade by night.

With the withdrawal of the escapes, the firefighters vacated the ‘Rest’, but left it where it was, and the tram workers continued to use it. But the end of the trams and the tram line came (too) soon, and a year after the firefighters vacated the ‘Rest’, so too did the tram workers, leaving it to generations of bus drivers, conductors, inspectors and messenger boys right up until the new millennium.

One morning in mid-January I pulled my bike up outside where the taxis park just beyond the Savoy on St. Patrick’s Street to see if I could place the whereabouts of where the ‘hut’ used to be. My father was a bus driver all his life and my uncle - his eldest brother Kevin - was a bus conductor for a while, which I only learned while writing up this piece. Growing up, the words “2 o’clock spare at the Statue” was kind of mantra in our house. To be honest, I didn’t really know what being 2 o’clock spare meant, and what a statue had to do with being spare, but to kids the world of adults is mildly incomprehensible and not really that important. Until you are one.

On Patrick’s St that January morning, I really couldn’t picture the ‘hut’ or where it used to be, so I stuck my head in, or near to in, the passenger window of a stationary taxi and asked the driver if he remembered the ‘hut’ that stood somewhere just across the road from where he was parked.

He did, and he told me that "only the other day” he was thinking about it, and the large flower bed that used to extend in front of the Statue. And then he mentioned Mangan’s clock - a tall stately clock - which is on the north east corner of St. Patrick’s Street, which I had completely missed and which has been around for decades. The taxi driver told me it was a famous meeting spot when he was growing up, couples would arrange to meet under Mangan’s clock, and he remembered it well, and the flower bed in front of Fr. Matthew and the ‘hut’ too, as he had went to school just up the hill in Christian Brothers College.

I imagine back then Mangan’s clock worked. One side of it is now broken, the clock stopped, while the north-facing face clock possibly works, but it’s either behind or ahead of time.

At one stage in our brief conversation the taxi driver asked me about the ‘hut’, and what happened to it.

The tweet-length version of the recent history of the ‘hut’ is as follows: it’s falling apart in a kind of purgatory below in a works yard in Fitzgerald’s Park. Briars have taken up resident where once firemen rested and bus drivers held court over ancient and not so ancient Irish history. Each day, each rain shower, weakens the fragile structure a bit more.

Although the ‘hut’ is hidden away out of sight in Fitzgerald’s Park, its existence is not a secret. When I popped into ask the security guard if I could see it, he kindly opened the gate to the yard to show me around and take a few photos of it. Since its decommissioning, it’s been vandalised and set on fire. One side of the structure is stitched up with cheap planks, but you can still make out the original ironwork design on the opposite side.

Surrounded as it is now by errant plants, bits of roadwork receptacles, it’s hard to believe that this small structure stretches back three centuries, through a civil war, a war of independence and the burning of Cork. Mark Wickham, the Dublin man who was instrumental in setting up the fire brigade in Cork in the late 19th century, collapsed while on duty in the ‘Fireman’s Rest’. He later died at home. The ‘Rest’ has long outlived him, but it’s hard to fathom what purpose it has now, except to fall apart, tucked away from sight, if not memory.

Memories

There’s still a generation of bus men in Cork who remember the hut for what it was: part and parcel of their working life. It was inevitable I was going to talk with Jack Lyons for this piece. Jack is a former bus conductor and post man, and I knew his name long before I knew who he was, as he’s more famously known as Jackie the Bell, a nickname he picked up while on duty-ish one day at the Statue.

Lyons, 78, also known as ‘Irish Jack’ from his time in London, was christened Jackie the Bell by a driver for not ringing the bell when he should have. This, of course, comes from when bus companies employed conductors. And buses had bells.

Jack is a meticulous note taker, document keeper and accomplished talker. He can recall his service number and an infinite list of the nicknames of his colleagues (bus drivers make the best nicknames: “Piece of Cake” and his son “Crumbs!”).

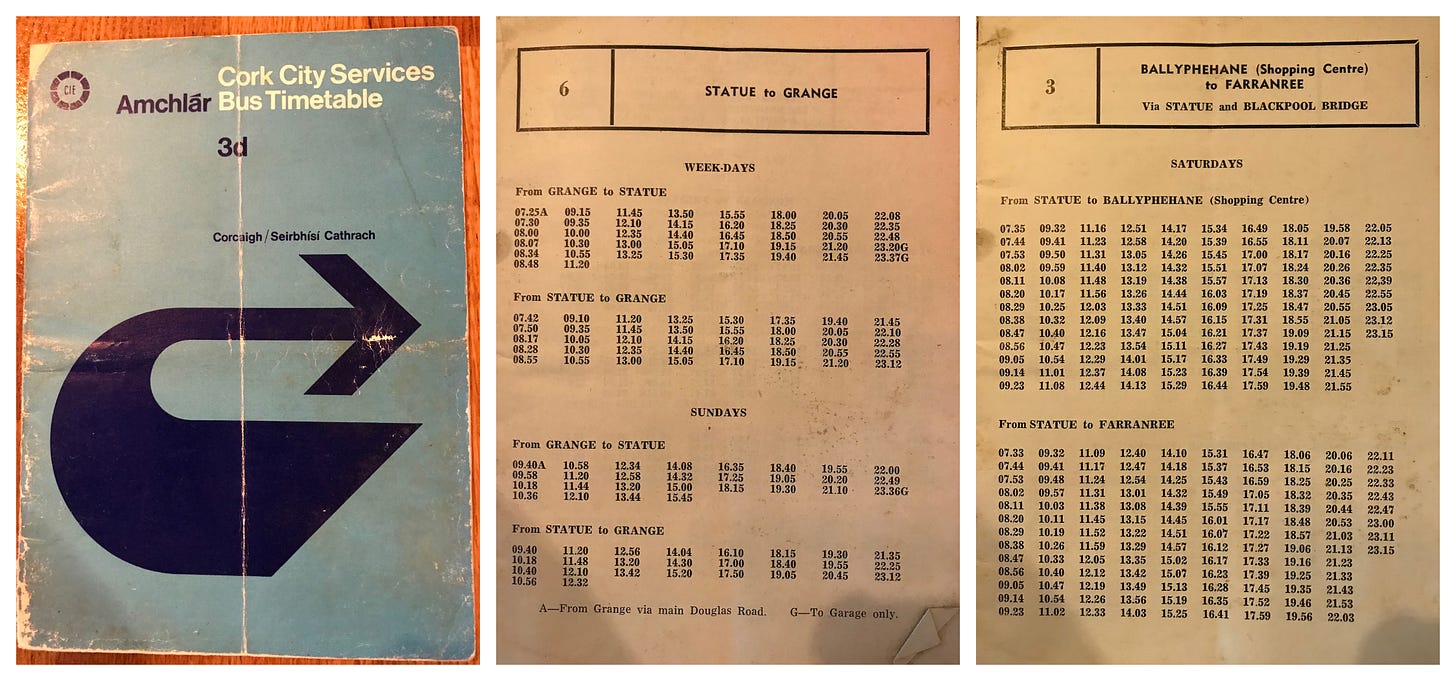

The ‘hut’ was still central to operations when Jack joined CIÉ in 1968. In bus man’s terminology in Cork, the Statue occupied an outsize role, as drivers and conductors had to “book on” (or check in there). Mind you, they weren’t checking in at the Statue, but rather the hut, but the Statue served as a landmark that everyone in Cork knew. It’s also worth recalling that you could drop by the hut and inquire as to what time the next bus to Mayfield or Gurranabraher or Bishopstown would be. You might get an answer and you might also get told where to go too!

There was always a supervisor on duty in the ‘hut’ and he was usually perched behind a counter at the back, as Jack explained. The ‘hut’ also contained boxes for bus rolls as well as boxes for machines for drivers booking on for late cars. (Drivers never referred to buses as buses, but rather as cars). The hut did not have a toilet, so drivers and conductors and inspectors would use the facilities down at Parnell Place as well as the public toilets on Merchant’s Quay and in nearby pubs such as Swan & Cygnet, The Bull’s Head and The Pig and Whistle. Some of them might linger a bit longer, perchance to quench their thirst. Such were the times.

Although he spent only a handful of years as conductor, Jack says they were good times. “You didn’t tell yourself then, ‘isn’t this a magical time?’”

“You gave out about everything and you probably said to yourself, ‘I wish things were a bit more modern,’” he says.

Space, or lack of it, was always a problem in the ‘hut’. It’s remarkably small and John Pearson recalls how in bad weather, especially when it was cold, crews would decamp to nearby shops, especially Roches Stores “where there was overhead heating.”

On John’s wedding day in 1973, his wedding car made a detour along Grand Parade en route from the Ballyphehane Church to the Country Club Hotel on the north side of the city. At first, John was a but flummoxed as to why they were headed up St. Patrick’s Street, as it wasn’t the most direct route to the hotel.

“I was shocked and surprised when ‘my limo’ stopped outside the ‘hut’ and was surrounded by a number of bus crews who covered and pelted the car with bus rolls to mark the occasion in style,” John recalls.

The Fitzgerald’s Park pilgrimage

In 2018, Jack and his former colleague Billy Nolan, a CIÉ bus driver, took a trip over to Fitzgerald’s Park to visit the ‘hut’. Jack wrote about seeing it again, and the flood of memories it brought on. Writing in the Holly Bough in 2018, he asked why it couldn’t be restored and erected somewhere prominent. He wants to make it clear though that he never wanted to start a campaign to bring back the ‘hut’. But, Jack’s been around the block long enough to know that if nothing has been done to restore and find a new home for it in 20 years since it’s been put out to pasture, then what are the odds that it will now, especially given the current and failing condition of it?

A spokesman for the Parks Department in Cork City Council said it would take “specialist work to reinstate it back to its original state.”

“At present there is no available funding to carry out remedial works but the Council is hopeful at some stage to have works completed,” he explained.

A few years ago Pat Poland, the retired firefighter and author, led a four-man delegation to City Hall to petition the Lord Mayor. Pat’s delegation had expertise in history and engineering, and they presented the then Lord Mayor with ideas of what could be done to restore the ‘Rest’.

“We suggested that it should be refurbished and a suitable bronze plaque, outlining its history and incorporating the logos of the three organisations with which it was connected - Cork Fire Brigade, the Cork Electric and Tramways Company, and CIÉ - should be attached to the outside in a prominent place. Tom Spalding, in particular, went to an awful lot of trouble in getting costings,” says Pat.

But as anyone who knows local politics knows that Lord Mayors in Cork, only really have the power to listen.

“The Lord Mayor while expressing interest in the project, could, of course, make no commitment, and that was the last we heard of it,” Pat said.

Councillor Kenneth O’Flynn raised the condition and future of the ‘hut’ at a council meeting in 2017. He told me that the council needs to get better at preservation, as its vital a way to understand our city’s history.

It’s an interesting and important question though, and I mean that in the way interesting is intended to be used: what do we preserve, and why?

It’s hard to fathom why the city council is holding on to the hut; on the one hand it’s an ‘orphan’, ending up with the council when it was removed to make way for the St. Patrick’s Street renovations.

Whether the ‘hut’ was kept for sentimental reasons, or there was a plan back then, it’s all moot now, as the hut is literally falling apart.

But, as they say, it doesn’t have to be that way. While I’m sure it’s an unintended consequence, but St. Patrick’s Street as it exists today is bland, and that’s a pity. Thankfully, there’s more space for pedestrians and people with disabilities to move around, but there’s little in the way of curios or heritage that jumps out at you. You could also add street furniture to the list of what’s missing from St. Patrick’s Street

If money, but more than that, imagination was channelled into the hut, it could be something. The question is what? The answer is many, many things. It could be Cork’s version of the fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square, with its rotating roster of public art exhibitions. Or it could replace the bland hut that’s been installed below the Tung Sing restaurant on St Patrick’s Street which Bus Éireann currently use.

The new ‘hut’ or ‘Rest’ could add colour to St. Patrick’s Street, it could certainly add history to the street. I can’t help thinking if the ‘hut’ had its own Instagram page, it might be the best thing that’s happened to it in years, because for the last 20 years it has slowly but surely been left to rot and fade into the museum of fading memories.

A fascinating read, JJ. I remember the Hut well and all the men who would congregate around it, smoking and laughing. As you so rightly say , we should treasure these seemingly insignificant but remarkable parts of our history.As my mother- in- law used to say : " their like will ne'er be seen again". I love your pictures ,too.