So much more than the rebel wife

Clonakilty poet Mary Jane O'Donovan Rossa was far more instrumental in the events that led to the Easter Rising than many are aware; a documentary by her great-grandson aims to shed light on her life.

“The fools, the fools, the fools! They have left us our Fenian dead, and while Ireland holds these graves, Ireland unfree shall never be at peace.”

Pádraig Pearse’s melodramatic graveside oration at the funeral of Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa in Glasnevin in August 1915, indeed, the entire event, with its massive attendance and global press coverage, is widely credited as having been an important trigger for the Easter Rising and the bloody path to Irish independence.

In a photo of the committee that organised O’Donovan Rossa’s funeral, the cortège of which drew 8,000 participants, you will see the faces of many well-known figures from the Rising and beyond: Pearse, Arthur Griffith, James Connolly, Thomas Clarke.

But one figure is conspicuous by her absence, despite her pivotal role in arranging the funeral: Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa’s widow, Mary Jane.

She was keenly aware of the public relations potential of the event. As an author, touring speaker and contributor to many news outlets, a woman with a high degree of awareness of what we would call PR today, she had purposely set about utilising her husband’s burial to leverage higher Republican goals.

She even wrote a letter, published in the extensive funeral programme pamphlet, reminding attendees that Jeremiah, despite rumours he had softened in his latter years, had remained a fervent nationalist intent on ending all British rule in Ireland up until the end of his life.

A poet and author who had for years helped her exiled husband to run a nationalist newspaper in New York, Mary Jane reportedly over-rided her husband’s own wishes to be buried in his native Cork, opting instead for the pomp, ceremony and publicity of a Glasnevin burial, where she purchased a plot for 20 pounds.

But almost exactly a year after his burial, in marked contrast to the publicity surrounding her husband’s funeral, having watched in horror as the events of the Easter Rising claimed the lives of so many of those from the funeral committee, she died herself, in Staten Island, in poverty, in a decaying family home that she couldn’t afford to repair.

Today, there isn’t a single monument to her name apart from the modest headstone at her grave.

“When she died, the imbalance was striking, between the headlines generated by O’Donovan Rossa’s death and hers,” Williams Rossa Cole tells me.

“News of her death was limited to a few small columns in some papers, often in the women’s pages or the beauty section.”

Williams is a documentary producer, and for years he’s been on a quest to commemorate the life of Mary Jane O’Donovan Rossa, his paternal great-grandmother, in film.

But he’s finding that, when it comes to women’s history, quite often there’s just not a lot to go on. Such large parts of their lives went overlooked and undocumented that recreating them for film can be a challenge.

An earlier documentary, Rebel Rossa, had Irish screenings at festivals during the 1916 centenary year and focussed on the life of his great-grandfather Jeremiah, but during the filming of this documentary, he became keenly aware that Mary Jane O’Donovan Rossa was being overlooked as a key figure in the Fenian movement in her own right.

Mary Jane was “as important to the Fenian movement as Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa,” New Jersey historian Judith Campbell tells Williams in the unfinished cut of his new documentary.

It’s an unfinished cut, but it’s nearing completion, despite the technical challenges of building a strong visual story about a woman of whom very little remains.

“The reason I was able to make a somewhat dynamic documentary film about Jeremiah, about someone that lived in the 19th century before our lives were being filmed, was because of all the commemorations that were happening while I was making it,” Williams tells me.

“All that happened for him, but for her there was really nothing. No commemorations, hardly any photos; I dug and found some articles. So production-wise, there’s nothing really there to film in a veritée way.”

“It shows me that there’s such a differentiation between women’s history and men’s history.”

“It boggles my mind sometimes to think how much women’s history there is, and how little is known. Maybe women’s history doesn’t get recorded in the same way, so it disappears, or it gets sidelined as a supporting role or something. But it’s not. It’s its own trajectory.”

Irish awareness of her is slender; there is no mention of Mary Jane in the Oireachtas online exhibition of the United Irishman that launched last year, despite her acting in a role that we would now probably call Deputy Editor on the publication, frequently, according to Judith Campbell, making sure there were “enough stories” and that the paper went to print.

The hand of Mary Jane is evident in the paper’s content, though; she was a nationalist poet since her late teens, and the United Irishman was so given to publishing poetry in its first year of publication that the newspaper published a letter by one W.G. in Houston, which read: “would it not be better if you were to cease publishing poetry entirely in its columns?... You ought to advise the Irish to quit writing poetry altogether. I believe it would be more to their credit to have less of it published.”

Williams, speaking to me via video link from his home in Williamsburg, New York, tells me he’d like to right what he perceives as a wrong, that he’d like Ireland to celebrate and commemorate Mary Jane more.

“Before Covid, when I was thinking a bit more ambitiously about the documentary, I was wondering if we could get Mary Jane’s remains disinterred and moved to Glasnevin,” he says with a laugh and a shake of the head.

“I corresponded with Glasnevin at one stage, asking them to at least consider putting a plaque to her on his grave, and they were like, ‘well, we have a monument to the women. There are plenty of monuments to the women.’”

This, as far as he is concerned, is tokenism rather than real progress: “It kind of feels like a little extra doling out here and there to make everyone feel comfortable, rather than a radical restructuring, at times. And we kind of need something that shakes things up a bit more.”

Even within his own family lore - his grandmother was Jeremiah and Mary Jane’s youngest, the author Margaret O’Donovan Rossa, and his father was author and editor William Rossa Cole - he says it’s hard to get a glimpse of what kind of person Mary Jane was, although the events in her life speak to a doggedly determined and high-spirited woman.

“Mary Jane is the one that really impressed me.”

“There was no-one to talk about Mary Jane growing up,” he says. “But when I talked to other parts of the family for the film, some of the older women said, ‘Mary Jane is the one that really impressed me.’”

West Cork to the Wild West

Born Mary Jane Irwin in Clonakilty, as a girl, she melded dual interests of writing and nationalism, penning romantic poetry, odes to the country she and so many others were busy creating in their minds: “Erin, I blush to be born of thee,” she wrote.

At 19, she married Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, a native of nearby Reenascreena. He was 31, heavily involved in the Fenian movement, and already a widower and father of five.

But while she was pregnant with her first child, in 1865, Jeremiah was arrested and sent to prison. He was incarcerated for six years, eventually released on pain of lifelong exile in 1871. But in the meantime, he and other prisoners were being subjected to cruelty amounting to torture, particularly in Chatham Jail, where he once spent 35 days in handcuffs, eating from a bowl on the floor.

Mary Jane and other wives and families of political prisoners were left without support.

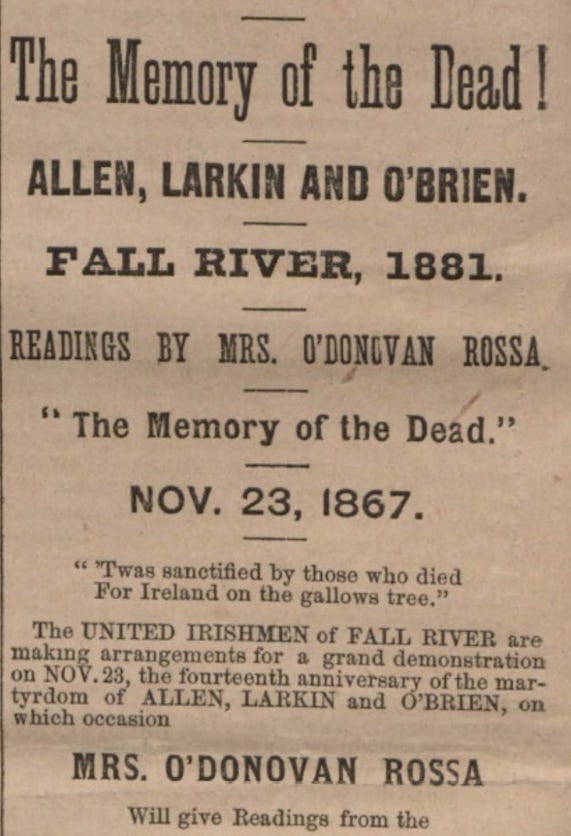

So as young wife and mother, she left her first-born, Maxwell, at home in Clonakilty and travelled to the US, where she took elocution lessons before setting off on a two-year speaking tour of the States.

She was reckoning on the support of the newly emerging Irish emigrant communities dotted about America, emigrants who had left during the trauma of the famine a generation earlier and were now both deeply embedded in their new lives and nostalgic for the country they had left behind.

“In the 1870s and 1880s, the Irish who had come here were starting to integrate and gain power in New York city, and across the country,” Williams says.

“It’s mind-boggling when you look at her readings around the country; there these pretty new Irish communities, everywhere from Butte, Montana to Idaho to Chicago.”

“You have to remember that this was just a couple of years after the Civil War; there were still Native American conflicts happening out there. But she was travelling around and doing huge readings with thousands of people, in Chicago, New Orleans, Canada.”

Celebrity

Young and beautiful, Mary Jane became a celebrity.

She would do readings, combining popular poetry of the day with her own work, before ending her events describing the mistreatment of her husband in British jails. She would give an impassioned plea for support for the fenian prisoners and for Irish independence. Coffers filled; she sent money to other wives and families as well as to Clonakilty to her own family and became, at 21, a woman of independent means while her husband was in prison.

She also earned some income from her book, Irish Lyrical Poems.

By the time Jeremiah was released from prison and made his way to New York to join her, she had ensured his instant fame.

Having done so, she rapidly performed a disappearing act, fading from public life herself as her husband became first famous and then notorious. It had been all very well for her to tour to represent her husband while he could not,

“She kind of disappeared, in a weird way,” Williams says. “That was her role at that point, after he came to New York. People knew her, and were demanding her when O’Donovan Rossa came to speak in places, but she just took the back seat.”

There were practical reasons for this disappearance as well as societal ones: Mary Jane gave birth to a total of 13 children during her marriage to Jeremiah, one in Ireland and 12 in the States. Just seven would survive to adulthood. It was not an easy life.

“I don’t think we, in the 21st century, can imagine what that was like, to lose so many children, sometimes literally every year,” Williams says. “They never had any money and they were always trying to get by. It wasn’t like they lived a glamorous life here; it was pretty harsh.”

Living on subscriptions

Brutalised from his prison experiences, Jeremiah set about raising money for his infamous “dynamite campaign”; he believed that Ireland would not be liberated from Empire without the use of violence.

A regular income was a problem, though. He tried his hand at being a hotelier, but became derailed by drink. Mary Jane had had enough.

Theirs was a loving marriage. Known as a hothead and an “uncompromising militant” in his political life, Jeremiah is described as a gentle man with his own family; letters show that he called Mary Jane by his pet name for her, Moll.

But by 1878, Mary Jane threatened to leave him, and took her children and went to stay with family in Clonakilty.

“I think she almost said, enough of this guy,” Williams says with a smile. “But they had a really intense love for each other and she had an equally intense love for Ireland and the idea of Irish independence. She knew that his life, and him being well, was very central to the prominence of the movement at that time.”

The couple reunited. The United Irishman was born. Subscribers most likely knew that the O’Donovan Rossas lived on the proceeds of the paper.

An American story, or a Clonakilty one?

Mary Jane’s story is essentially an American one, despite her maintaining close connections with Clonakilty throughout her life. It’s where she settled, and it’s where her children were born and buried, and it’s where her descendants still live.

“She spent most of her life here,” Williams says. “She went back and forth a lot, but she did build her life here. And it was pretty hard here, but potentially a lot harder in Ireland at that time.”

Williams has been working on his documentary, Rebel Wife: Mary Jane Irwin O'Donovan Rossa, since 2017. Life, and Covid, have gotten in the way of the completion of the project.

He’s been working as producer on a film with Academy Award winning documentary director Barbara Kopple. “Long story short, I’ve been gainfully employed, rather than working on these passion projects, so that was sort of a distraction, but then of course Covid-19 locked everything down and stalled so many plans,” he says.

Williams is now back on track to finally get the project, which has received some funding from Cork County Council and the New York Irish Institute, complete. And he hopes to be able to arrange screenings at Irish film festivals in the not-too-distant future.

“I don’t think it will be a feature length, but a strong hour long TV cut, which is 45-50 minutes,” he says. Post-production work of editing, sound design and the like are underway and Williams has a GoFundMe page for anyone who wants to support his passion project.

“Anyone who wants to support it will get credited and I obviously hope it will get screened around Cork as well,” he says.

One scene in the film that Williams shot while in Ireland in 2017 shows a committee meeting to discuss a commemorative bust of Mary Jane in her native Clonakilty. This project has not come to fruition and Williams would like to see it happen; he hopes that his film can also serve to raise public awareness and ideally get this project off the ground again.

The Michael Collins museum has a room devoted to Jeremiah and Mary Jane, but there is no monument to this powerhouse woman of Irish history in existence, anywhere. Williams would like to see that changed.

“Mary Jane O’Donovan Rossa is one of Clonakilty’s most influential people, along with Michael Collins,” he says. “There have been efforts to commemorate her, but I see my job as to push that further.”

The GoFundMe page for Rebel Wife: Mary Jane Irwin O'Donovan Rossa is here.

Excellent piece, Ellie. Would be good if Clonakilty did its bit to honour this woman.