Seeing the woods for the trees in Ballymartle

In the village of Riverstick, a campaign to stop Coillte from selling a portion of woodland into private ownership is underway, with locals saying they want more public walking trails on the land.

If you go down to the woods today, you’ll never believe your eyes…..

Especially if you’re a Riverstick local out walking your dog and you see a “For Sale” sign appear on Coillte-owned land at Ballymartle woods.

This is what happened to Anna Maria Mullally last November.

The 95 acre woodland, located a kilometre outside Riverstick village on the Kinsale side, had become a lifesaver throughout the Covid lockdowns of 2020, and Anna Maria, a lecturer who moved to Riverstick 20 years ago, had developed a heightened appreciation for forest rambles in the company of her dog, Raf.

“At first, I thought it might be some farmland close by or something, so I posted on Kinsale and Riverstick noticeboards on Facebook, asking about it,” Anna Maria says.

Nobody knew anything.

Eventually, other walkers in the woods told Anna Maria that they’d heard on the grapevine that it was indeed a parcel of the state forestry agency’s land that was on the market.

Anna Maria was stunned. She posted on Facebook about it, and soon after, other area residents started weighing in: Andrew O’Connell, 21 and a student at CIT, organised an online petition that has gathered just under 1,500 signatures. A Facebook page, Save Ballymartle Woods, was started.

Riverstick Walkway Committee was formed: instead of Coillte selling the land into private ownership, they are campaigning for the land to remain publicly owned and for Coillte to work with locals to improve the forest amenity by creating a series of trails.

“As soon as I saw Anna Maria’s post, I organised the petition,” Andrew, who has lived in Riverstick all his life and who has family in the area going back generations, tells me.

I meet Anna Maria, Andrew and Margaret Kelly, a third member of their core group of six, on a bridge over the River Stick: yes, Riverstick has a river running through it that’s named Stick. Before the construction of the busy R600, the main Cork to Kinsale road which now carves up Riverstick Village, this bridge was part of the infrastructure of the old road.

“My mother remembers when this bridge was on the main road to Kinsale,” Andrew says.

We set off on a walk of the woods, with Raf straining at his lead and occasionally wrapping it around our legs.

From our meeting point, we can see the parcel of land that Coillte want to sell. The asking price was €120,000, but the group don’t know what the sale price was: what they do know is that on January 11, while they were in the process of submitting a proposal that Coillte had invited them to submit, and which they submitted on January 14, a Sale Agreed sign was put up by the auctioneers.

“We were told to fill out this application form, and submitted it on the 14th of January; Christmas is a busy time,” Margaret Kelly says. “We had asked them to let us know the status of the sale, and they never came back to us: the Sale Agreed sign just went up.”

“How can genuine engagement take place if it’s already sale agreed? It feels like a done deal.”

Public consultation

Coillte have a published engagement policy which states that they will “ensure that all persons living and working in the environs of our developments are kept informed of ongoing and proposed works throughout the project lifecycle.”

Riverstick Walkway Committee clearly feel that this is not the case in this instance.

Coillte, who employ PR agency Carr Communications to handle press queries, sent me an email through their PR spokesperson in response to queries I sent them. In it, they said they had held “a number of on-site and virtual meetings with local public representatives and community groups in Ballymartle over the last three months.

Whatever other meetings Coillte have held, Anna Maria, Margaret and Andrew say they’ve met with Coillte twice: once on November 29 and once on January 31.

Private sale, public land

A major communications sticking point for locals has been uncertainty over what would end up in the woods following a sale to a private landowner.

Rumours went around that the proposed buyer wants to develop an eco-glamping site on the land, but this was not confirmed to RWC members until their January 31 meeting, although it was mentioned in a phone call to one member by a Coillte representative before this date.

It seems that Coillte’s sale of the land was precipitated by an interest expressed by this unknown, but apparently local, business owner.

“Coillte was originally approached by a local in Riverstick who was interested in developing a forest-based tourist facility in Ballymartle Forest,” Coillte’s statement to me said.

“Coillte understands that if the sale were to proceed the area for sale would remain under forest. The intention of the local interested party is to enhance this land with a potential recreational offering that will benefit the local community.”

Firstly, Anna Maria points out, it would not be possible for the entire parcel of land, currently under young native species with a small planting of older commercial conifers at its heart, to remain under forest: no access points to the land have been described, there are no clearings on it.

Secondly, once land is in private ownership, there is no longer any certainty as to its long-term future.

“Once it’s sold, it’s out of our hands,” Margaret says. She points out that businesses can and do fail, and that land can be sold on: of course any developments are subject to planning applications, but these require time and resources for communities to keep on top of, make submissions on and dispute where necessary.

What public enhancement does a private, paid tourism offering bring to the woods, I ask?

Anna Maria laughs: “Is that a rhetorical question? None, of course, unless you’re a paying guest. In fact, we even believe that making Ballymartle woods more visible and improving the trails would do more to attract visitors to Riverstick than than a glamping site.”

“Coillte have maintained throughout that we shouldn’t worry about the land, that it would remain a public amenity. So we asked them to explain how privately owned, glamping facilities could be considered an amenity and they weren’t really able to give much of an answer to that.”

“Coillte buys and sells land for a range of reasons including the expansion of our forests, facilitation of our neighbours, local communities, schools and businesses and to support strategic national objectives such as tourism, regional development, renewable energy and other infrastructure projects,” Coillte’s press spokesperson wrote in their statement to me. “In 2021, Coillte bought over 580 hectares of land and sold less than 300 hectares.”

But none of the people I’m talking to today see this as helpful: why would it benefit Riverstick for the proceeds of the sale of part of Ballymartle to be diverted to another amenity?

In the email I receive, I am told that Coillte will use some of the proceeds of the sale to improve parking facilities at Ballymartle, where drivers accessing the walk currently park on the side of the laneway.

But Anna Maria tells me she’s astonished by this, that this was never communicated at their meeting on January 31.

Precedent, and remit

“Based on this, does it mean that anyone can approach Coillte and say, I’ve got an idea, I’d like to buy a piece of your forest and develop it and don’t worry, it’ll be for the public good?” Anna Maria asks.

“Coillte seems to be run, by and large, by people who are looking at spreadsheets, not the people on the ground who understand what’s going on. And a spreadsheet can’t capture the value of an amenity like this to a community.”

Margaret agrees: she thinks Coillte’s dual remit of profiting from forestry and providing public recreational space needs to be re-examined.

She says there’s a growing awareness of the importance of biodiversity, the value of the nature on our doorstep.

“There’s a citizen’s assembly on biodiversity coming up, but there should be a broader conversation about Coillte’s dual remit, I think,” she says.

“Our query is how private ownership can benefit the community and the public good? It’s also the broader questions: how can a state agency for forestry have a dual remit of having a commercial objective, and at the same time, having a recreational objective? For us, the two just aren’t aligned.”

“Part of Coillte’s argument is that the land is sold here but it’s purchased elsewhere, and there’s amenities purchased elsewhere. They say that for any felling here, there’s replanting somewhere else. That might balance the books in Coillte, but it’s not thinking about the broader picture, how communities can be partners in these projects.”

Seeing the woods for the trees

It’s a beautiful spring day, perfect for a walk in the woods.

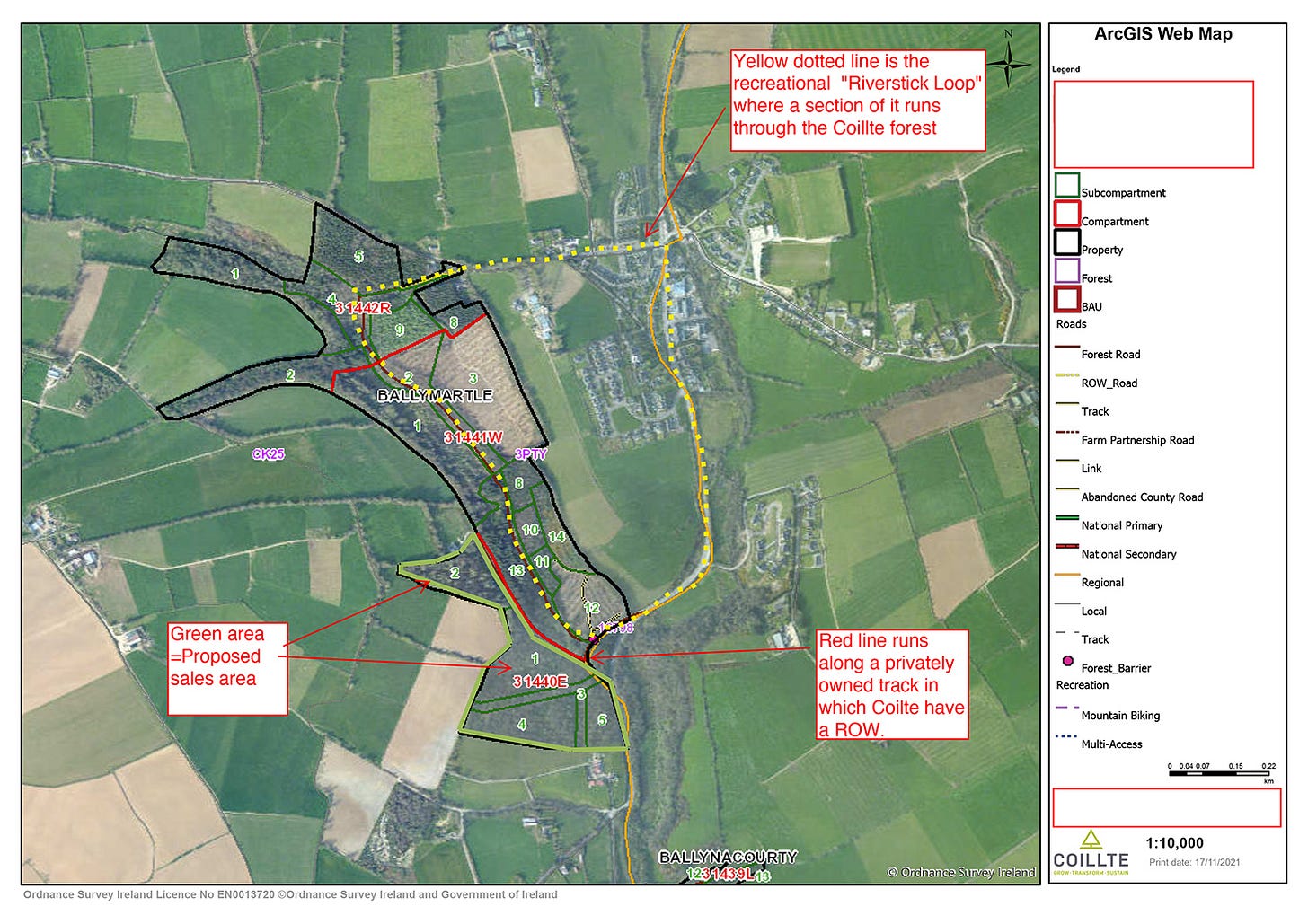

As we stroll along, we are walking along a good trail surface maintained by Coillte in the portion of the woods not under sale: Coillte argues that the 22 acre plot they wish to sell has no public trails on it and is not in use by the public, but RWC want to create a looped trail that would incorporate the 22 acres.

At the side of the path, in a clear little ditch of water, frogs are spawning. We stop to look at the activity: some are mating and some are laying, and big clouds of gelatinous spawn are filling part of the ditch.

Andrew says he has never seen frogs here until this year, when his renewed interest in the woods saw him visiting more and observing more.

For the village, which had a population of 590 at Census 2016, the past couple of years have brought the importance of their local woodland amenity into focus, Margaret tells me. During the bewilderment of that first lockdown in spring 2020, parents arranged for local children to install fairy doors on some trees.

“It was actually quite moving to see,” Margaret says. “There are familiar faces, if you come here often. It was nice in lockdown to just see a different face, to see your neighbours.”

“It wasn’t only dog-walkers using it, whole families, maybe people with small children needing to get out of the house, were up here building bivouacs, developing their outdoors skills.”

Margaret, who works in community development, grew up in Riverstick but moved away for college and then lived in Brussels for several years.

“I was away for quite a while but when you come back to this, you realise how unique this area is and you see it through different eyes,” she says. “In Brussels, to get to real countryside or nature is a trek: it’s all very organised and maintained and sanitised, whereas here, there’s something to be said for the natural beauty of it.”

“When I was younger, we called the woods The Green Gates because there were old gates, and I remember it being really overgrown with laurel and bamboo. It’s only since I came home that I’ve been using it as a woods for walking.”

Bringing people together

If there has been a positive to the saga so far, it has been in how the community has rallied around, they tell me. They are fostering and building a sense of unity, and they say that their core group of six members who actively organise is surrounded my widespread support.

Indeed, Andrew, Anna Maria and Margaret, who all live within a few kilometres of each other, had never met until they were involved with this campaign.

Does a bear shoot in the woods?

We cross a tributary of the Stick to walk up to the boundary of the 22 acres of disputed land, which is furthest to the South West from Riverstick village. We enter a weird terrain indeed: a local archery club with a membership of around 50 have an arrangement with Coillte to operate here, and they have a bizarre and sometimes eerie array of targets dotting amongst the trees.

A bear, a panther, a boar, even a cobra can be stumbled upon.

Further on, we walk through a low, swampy area that Anna Maria tells me they believe was once an ornamental lake for Ballymartle House, with which the woodland was originally associated. They believe the land came into state, and some private farmers’, ownership at the hands of the Land Commission following the War of Independence.

There’s a lot to learn about this woods. At one stage, while I’m taking a photo, a squirrel dashes up a tree behind me, to Anna Maria’s delight. Deer have been spotted here. We see badger setts, evidence of all sorts of animal life. I find myself putting it on my mental list of nice walks: how come I’ve never been before, and know nothing about it?

Sale on pause

Coillte has currently agreed to pause the sale process of the 22 acre plot of land, despite the Sale Agreed sign which is still displayed at the roadside. They say they hope to have more meetings with locals “in the coming weeks.”

RWC are discussing their options for a counter-proposal that they say will enrich lives in this commuter-belt village.

“What we would like to do is create a whole perimeter loop, and to be able to close the loop too, by making proper trails in the 22 acres,” Anna Maria says.

Coillte’s argument that this patch was barely in use anyway is “not enough. We want the forest left untouched and we want it as recreational space. We are prepared to work with them in partnership to achieve that.”

“What we have said we want to do is develop the loop and bring our the heritage and biodiversity aspects and connect to the new walkway to Belgooly, anchoring ourselves more and articulating more fully the history of the area.”

Cork County Council already have plans for a children’s playground and picnic area in an adjacent patch of land to the woods, and work has begun on an off-road footpath to this so that villagers don’t have to brave the perilous conditions of the R600 to access this amenity, which is in the draft Cork County Development Plan.

Ultimately, there is a plan afoot to link Riverstick, Belgooly and Kinsale with a safe off-road path the entire distance.

Coillte Nature is the not-for-profit subdivision of the state forestry company. The Riverstick residents have asked Coillte if Ballymartle Woods could be a project under its remit.

“Our preferred option would be for Coillte to hold onto it and manage it,” Anna Maria tells me.

“But they told us we’d have to put up a lot of money, that the Dublin Mountain Partnership had raised millions in funds. We can certainly do some crowdfunding, but why is a State Body telling a community group that they have to raise money for something that’s for the public good? It’s a State agency: it’s our agency. That might be naive, but they are working on behalf of the Irish public.”