Remembering the wail of the Banshee

Kenny Morris now lives a quiet life in Cork city, but as drummer with Siouxsie and the Banshees, he was at the epicentre of the brief creative maelstrom that was punk in London in the late seventies.

He’s a small, quiet, well-mannered man living in a cottage in Blackpool in Cork city.

But once, many years ago, he inspired Siouxsie Sioux to write her venom-laced song Drop Dead, the opening lines of which go:

I hate you, I hate you!

I hate you, I hate you!

Drop dead!

You stinking little creep

Drop dead!

With your emotions so cheap

Your poisoned mind,

It's disgusting everyone

We don't care if you vanish in thin air!

It goes on in this vein for several more verses. But Kenny Morris doesn’t seem to mind. In fact, he has a little chuckle when the subject of the song comes up.

The first time I met him, in a city café, thin and smelling of cigarettes and wearing a colourful assemblage of clothes and a pair of fingerless gloves, he told me the difference between walking down the street with Sid Vicious and being on your own with Sid Vicious: how the poor kid had to live up to his name, barely able to make it down a single street without some sort of violent altercation.

But how, on his own, he was shy.

“He never showed his shy, considerate, childlike side in public,” Kenny tells me, the second time we meet. Kenny knew Sid Vicious quite well: in fact, he was the drummer in The Flowers of Romance, the band Vicious formed before his ill-fated stint with the Sex Pistols.

And then, Kenny was the drummer in Siouxsie and the Banshees. For two albums.

Today we’re sitting in Kenny’s red brick cottage. It’s crammed with his artworks, with a token nod to the festive season in the form of a string of coloured lights on the windowsill. It’s also liberally bedecked with sheafs of paper, neatly organised into chronologies: he’s been working on his autobiography.

“Writing has been a bit like an exorcism of myself,” he says. “It’s enabled me to look back at my past; put it in perspective, see where I am now. I can’t live without it. It enables you to loosen even some of the toughest ribbons in your past.”

The explosively eventful punk period - his brief but impactful time in Siouxsie and the Banshees, the circumstances around his exit - is a particularly large tangle of ribbon, it seems.

Kenny Scissorhands

Kenny grew up in an Irish family, in suburban Essex. By the time he was attending school he knew that his biological mother was someone who he had believed to be his aunt, the sister of the mother who raised him, Angela.

It was such a common story those days. His biological mother got pregnant in 1956, left Ireland.

“She decided not to have an abortion, but to get me adopted,” Kenny says. “I know she had a really difficult time because everywhere she went was No Blacks, No Dogs, No Irish. She just got lucky because her older sister Angela and her husband Peter were unable to have children. My dad said, ‘we’ll adopt him.’ My dad had a really kind side to him.”

Kenny has vague memories of borrowing Angela’s cake tins and using them as drums to play along to the radio: Beatles mania was at its peak when he was a child and he too was enthralled.

“I thought I definitely wanted to be in a rock’n’roll band when I grew up,” he says. “Everything about the lifestyle, even at that age, appealed to me.”

But he’d already been showing signs of other creative talents: as a preteen, he won a school poetry competition and squirmed with embarrassment as the headmaster read his effort out at assembly. After school, he would complete a first year in Camberwell College of Arts and develop a keen interest in photography and film.

Having already worried his parents with an androgynous Bowie phase, Kenny courted the skinhead look, but drew the line at a shaved head for fear of getting in trouble with his parents or at school.

But after school, having moved to London for college in 1976, he transformed himself.

“I didn’t come back to visit for three months and when I did, I had a totally different look,” he says. “I’d dyed everything black and I was wearing chains and studs and leather trousers. I looked like Edward Scissorhands.” He laughs.

“I was thinking, mum’s going to fuss and I hate that, oh no, here she goes, and dad could barely look at me, he’d just grunt.”

He shows me a picture, the one he wants on the cover of his autobiography.

It’s true, he did look like Edward Scissorhands.

Then was the winter of their discontent

Although the current round of UK strikes are engendering a lot of “unprecedented” descriptors in the press, in fact, the late seventies were a time of even greater upheaval, really what looked like the brink of all-out societal collapse.

Energy crises, widespread unemployment, strikes amongst everyone from NHS workers to gravediggers…the Jim Callaghan Labour government that predated Thatcher’s election in 1979 had every bit as much on its hands as Rishi Sunak’s has today. And more.

Young people began to embody the violence, ruthless remnants of Empire-driven capitalism and class warfare that surrounded them, while at the same time revolting against restrictive suburban norms. They would be iconoclasts, ugly, shocking. After the optimistic idealism of the sixties and a brief foray into the gender-bending fantasia of Glam Rock, punk was born, bloody and screaming and ready for a scrap.

In Derek Jarman’s punk film Jubilee, shot in 1977 and released in ‘78, Elizabeth I is brought back to life to witness her nation’s descent into anarchy.

“As long as the music’s loud enough, we won’t hear the world falling apart,” one character says.

Kenny, of course, was working as an assistant on that film.

Both Derek Jarman and John Maybury were friends. Later, he would produce his own arthouse films, but after one year at Camberwell College, in the summer of 1977 he was torn between heading to New York and immersing himself in the Studio 54 scene and staying in London, which he judged to be the more fertile creative land at the time.

Shock tactics

Jubilee certainly adopts punk’s shock tactics in terms of imagery. Some of the lengths to which that generation went to be controversial and confrontational are hard to understand from this remove and would be considered unpalatable or downright taboo today. Like the time Kenny first met Siouxsie Sioux, at the Screen on the Green Cinema in Islington, in August 1977.

The venue is renowned for several punk gigs, including a showcase organised by punk impresario and puppet master Malcolm Maclaren a year earlier, where The Clash and Buzzcocks supported The Sex Pistols.

Kenny clears his throat and reads to me: “The Bromley contingent occupied the front row and Siouxsie stood out, dressed as she was in black fishnet stockings, a black strapless bra and a Swastika armband. Although we didn’t speak, we made eye contact and for one lingering moment I had the undeniable feeling that we were going to do something special together in the not-too-distant future.”

Siouxsie, originally one of the “Bromley contingent” who were Sex Pistols hangers-on, was first catapulted into the nation’s gaze when she appeared in an odious TV interview with presenter Bill Grundy - who openly and casually propositioned her live on air.

That interview was the subject of a great deal of controversy and scaremongering in the red-tops with the result, Kenny says, that casual violence against anyone who was dressed like a punk became common.

“Every Saturday, all these Teddy Boys would arrive at Sloane Square Tube Station and they’d walk all the way down the King’s Road to World’s End,” he says. “God help you if you were a punk-looking thing, and it happened to me a couple of times.”

“There were what we used to call the Plastic Punks, people with Mohawks and all the style but totally illiterate as to the ethos as to what Punk Rock was about. Tourists would pay them money to take their pictures. Then they’d meet in World’s End every Saturday for a huge punch-up. I wanted no part of that, are you kidding?! But that used to happen every single weekend.”

The lengths to which Siouxsie would go to shock and provoke were a step too far for Kenny on many occasions. “She got us in an awful lot of trouble from day one,” he says. “She said, ‘I like getting people’s backs up, it’s like laughing at spastics.’ I’m sorry Siouxsie, but that’s not fucking funny. It’s not necessary, it’s unforgivable.”

Many of the familiar faces from that time had far more dysfunctional backgrounds than Kenny’s largely loving and supportive family home: John Simon Ritchie, AKA Sid Vicious, was given his first heroin as a birthday present from his mother.

And Susan Ballion, or Siouxsie Sioux, also came from struggle: her father was an alcoholic and her mother schizophrenic. As a teen, she had been sexually assaulted, and she would be diagnosed with ulcerative colitis shortly after her father’s early death. She would feign suicide to get her mother’s attention, lying at the bottom of the stairs in the dark and waiting to be found.

Early Banshees songs like Staircase Mystery and Suburban Relapse were based on these experiences, although Kenny says the band never talked about their emotions or personal struggles and he had no idea what was going on for her.

“I was only in her house once, in 1978, before we were signed to Polydor,” he says. “She still lived alone with her mum, who had told her never to invite friends around. The house was surrounded by tall foliage that blocked out any daylight and had the décor of a funeral parlour.”

“That visit told me everything I needed to know about her formative years, which had all the tension and drama of a Hitchcock movie. Her mother shuffled into the living room with a tray of tea and biscuits and then disappeared back to the kitchen.”

When Kenny first saw Siouxsie and the Banshees perform, Sid Vicious was on drums, for the first and last time.

“When he came off stage, I said to him that I really liked what he did,” Kenny says. “He kept a really simple beat and kept the cymbals to a minimum. I told him he was like my favourite drummer, Maureen Tucker of the Velvet Underground. He said he’d never played drums before in his life.”

The Flowers of Romance were born: a loose conglomeration including Vicious, Viv Albertine and Palmolive from The Slits, guitarist Marco Pirroni, and Kenny on drums.

Later, when Malcolm Maclaren wanted Sid Vicious for the Sex Pistols, the Flowers would disband, not having recorded anything. Kenny went to audition for Siouxsie and the Banshees. Typical of the extremely makeshift musical approach of those punk bands, he found that they had a gig in two weeks, and a sum total of four songs learned.

“When I turned up for the audition, there was some drum kit there and I was fiddling around trying to figure out how to even set the thing up when Nils Stevenson, the Banshees manager, came up to me: ‘You’re supposed to be a fucking drummer aren’t ya?’ I took an instant dislike to him. But by the end of the audition, we had eight songs.”

Photos

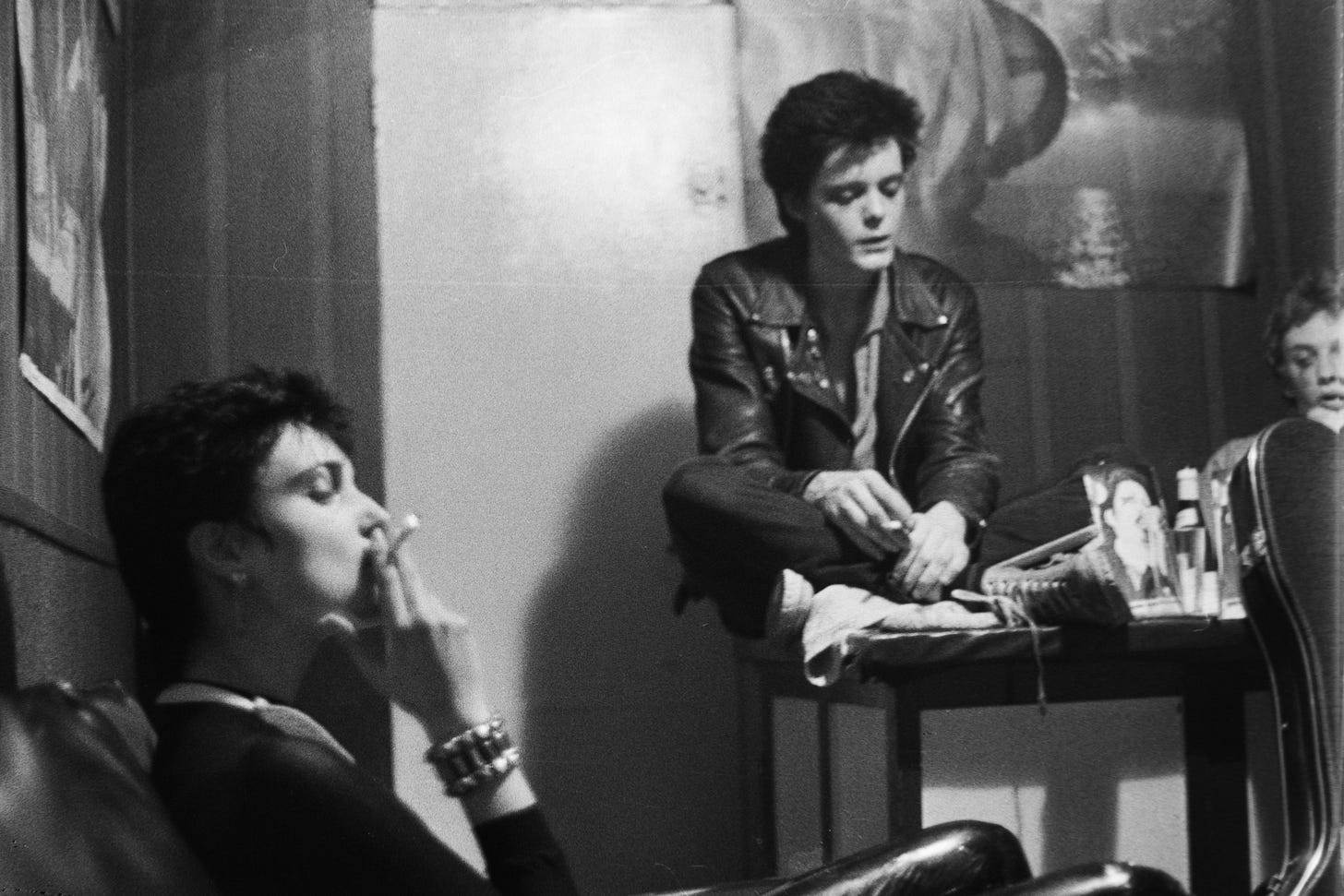

Because he was also an art student and photographer, Kenny is in possession of a truly extraordinary, never before seen, collection of photographs he took of the era in all its breathtaking squalid glamour: A young Viv Albertine sitting in the corner of a flat covered in detritus, Siouxsie at rehearsal, arms folded, looking pensive, smoking a cigarette. A mannequin in bondage gear having its nipple licked.

There’s a pair of passport photos on top of a stack of papers on his fridge, of Kenny as a young man. In one, he is tousle-headed, beautiful and serious. In the other, his head has been cut out. I ask him why he has cut out his face in the second image and he says he doesn’t know, can’t remember. For a collage, maybe?

Interviewing Kenny is a little like this duo of images: sometimes a clear picture of him emerges, but sometimes there’s a curious absence, like there are things he doesn’t want to discuss. When he’s tied for words or can’t remember exact dates, he resorts to reading tracts of his own writing, which I am loath to transcribe and use but which have made their way in to a couple of the quotes in this interview.

Kenny spent just two and a half years with Siouxsie and the Banshees, recording debut album The Scream and it’s follow-up, Join Hands, as well as several successful singles, including Hong Kong Garden.

His unorthodox, self-taught drumming style used almost no cymbals: he would turn his sticks round the better to belt his drum kit as hard as he possibly could. Siouxsie said he was like a marionette seated at his kit.

“I was really physical on the drums,” he says. “When I eventually got my own kit, it had to be practically specially built. I think it was ’78 before I even got that.”

“I had a Pearl Drum Kit with a special indestructible pedal. When most drummers use a ride cymbal, I didn’t want a ride. I’d have my high hat and a crash and an upside down Chinese cymbal. I would play time on the side drum, not the ride. When I got a riser, I made chalk marks where they had to drill holes and attach metal clasps to secure the cymbal stands.”

Kenny’s descriptions of the chaos of those years is hilarious and tragic in equal measure: touring with Siouxsie while she had a severe throat infection from someone spitting into her open mouth while she was on stage; the band’s office, littered with papers, often flooded, with a phone that rang and rang and rang unanswered.

Their manager, Nils Stevenson, had a drug problem. Once, a friend of the band’s apparently found a Siouxsie and the Banshees chequebook on the lid of the toilet in Nils’ house.

Kenny says he dabbled in heroin “a few times, but I never got addicted. I saw what it was doing to people that I knew.”

Despite two well-performing albums and several singles under their belt, Kenny was on just £100 a week, out of which he was covering his rent and other expenses.

He didn’t understand why they could be earning so little. Communications within the band were poor during the recording of Join Hands, and it was during the tour for this album, while in Aberdeen, that the proverbial excrement hit the proverbial fan.

It’s a tale that’s been recounted many times, but Kenny and guitarist John McKay left a record signing following an altercation where Siouxsie punched McKay. They got into a further violent fracas when the rest of the band caught up with them, and fled in a taxi, ditching the tour and the band.

“When we left the record shop, we went outside and went, ‘what are we going to do?’ So we went back to the hotel. Margaret Thatcher was staying there too, so security was everywhere: guys talking into their sleeves.”

They booked a taxi but, fearful of the rest of the band catching up with them, lied to the receptionist and said they were going to the train station when in fact they were headed to the airport.

The band did arrive, just as they were leaving.

“Nils came up to the taxi and reached in through the window, and started trying to strangle me,” Kenny says. “So I wound the window up on his arm. He fell to the floor and he was going, ‘I’ll see you never work again. I’ve invested 45,000 in this tour!’ and John was going, ‘have you? Whose money? Is that our money, Polydor’s money?’ Things had gotten that bad that we didn’t know.”

The aftermath of the split seems like a dark time: back in London, but now without a flat, he moved into John Maybury’s squat near the Albert Hall. Other offers from bands came in, including with Adam and the Ants, but Kenny wanted nothing to do with the music industry.

“I was kind of on the edge of a bit of a black hole,” he says. “But I had a feeling instinctively, underneath it all, that maybe it was meant to be, that the timing was good.”

He would go back to art school, complete a degree and, if filmmaking is an exorcism as much as his writing is, then his debut short film, La Main Morte, seems exactly that: it’s an allegorical account of the Banshees break-up, narrated by Dorothée Lalanne with music by Kenny and pianist Jean-Pierre Baudry.

And then what? He painted, made art films, moved to Ireland to teach art in a Kildare secondary school in 1993, and to Cork in 2010. In part, he says, because he was impressed by the scope of the music and art scenes in such a small city.

He doesn’t have much contact with most of the figures that populated his life in the punk years. Siouxsie and the Banshees went on to record some of their most critically acclaimed records after Kenny left, with drummer Budgie, who eventually became Siouxsie’s partner.

The last time Kenny saw Siouxsie was when she was playing with The Creatures in Dublin, in the late nineties.

“I think it was 1999, and they were playing at a place in Templebar,” he says. “Afterwards, I went backstage and had a good old chat with her: we got on like a house on fire, like nothing had ever happened. But she had come around to see me when I was living in Kensington and had we ironed out our differences.”

The good thing about her volatile behaviour and quick temper, it seems, is that she also doesn’t bear a grudge.

“Once I phoned her up while she was living in France, and I was telling her that we should record a cover together, I think it was a John Lennon song. But then I thought, actually, it would be much better to do Drop Dead,” Kenny says with a little smile. Siouxsie has said that Drop Dead was written about Kenny and John McKay, but she’s also denied it.

Having painted and had occasional exhibitions of his art in Ireland, Kenny is anticipating a renewed interest in all things punk during the plethora of anniversaries that will kick off in 2025, 50 years after the Sex Pistols were formed.

He wants to publish his own memoir in 2026, and is envisaging photography exhibitions too.

Kenny can be quite hesitant in conversation, frequently gathering himself for long intervals before speaking. But there’s no hesitation when I ask him if now, at 66, he still considers himself a punk.

“Yeah.”

“It’s an educated tribal attitude; at best, that’s what punk is. And it’s forever put a dent in the clay of our global DNA.”

So much footage exists of this era, and it’s easy to understand, once you cut through the shock tactics, to see the intent behind these young people’s iconoclastic urges. If you’re living in a world rife with unfairness and rigid class hierarchies and gender boundaries, and you don’t want a part of it, you have to destroy before you can rebuild.

And so the wave of moral panic they created was predictable too: the status quo does not want to surrender.

Kenny sees it as a cyclical condition.

“Usually every ten years something happens in youth culture,” he says. “Look back as far as the 50s: we had Mods and Rockers, and then Prog Rock and Glam Rock. It’s always related to music.”

Punk’s purposeful rudimentary nature, he says, was in part a response to the bedazzling glitz and expensive stagings of the Glam wave that preceded it.

“Most of the groups you might go and see were people like ELO and Rick Wakeman,” he says. “You’d be looking at them and going, ‘ok, what are we going to do?’ To go against it and get them to move over and give us a chance, we were going to have to strip everything back to the bare bones.”

“The whole idea of not needing to play an instrument became very viable. It was more about a kind of atmospheric attitude, something totally different that record companies wouldn’t even recognise. Only young people around my age understood that.”

I ask him if they were misunderstood, those snarling punks with all their posturing, their outer desire to shock, disrupt and destroy.

The answer is as unexpectedly, subtly beautiful as its subject matter. What they were really doing, Kenny says, is celebrating and elevating imperfection. An artistic outlook not without precedent.

“During the Ming dynasty, the master potters would leave an imperfection on each piece to remind us of the importance of humility in the greater scheme of things,” Kenny says.