Rate my park Cork - the pandemic edition

Mick O'Sullivan and a small army of volunteers used the third lockdown to take a good hard look at green spaces in Cork city.

On lockdowns

By the time the third lockdown arrived earlier this year, there was, at least, some kind of routine built into it. We knew from experience how constricted our lives had become, even if we didn’t quite know how long restrictions would last for. We knew there was plenty of things we couldn’t do and plenty of places that were off limits. That proverbial oyster was somewhere between two and five kilometres from your front door.

So where do you go in Cork city, when you can’t go very far? The choices had been distilled down to two: you stay home (and go online) or you go outside, to the shops or to that communal space beyond the commercial sphere where nature exists to some extent: the local park, if there is one.

Call and response

There was kind of a pandemic-induced “era feckit I’ll do it now” logic to how Mick P. O’Sullivan ended up - or started out - with his idea to rate every park in Cork city. Certainly, nobody asked him to do it and it wasn’t work related. (Mick works as an architectural draughtsperson with University College Cork’s buildings and estates office).

Like others, he had a bit more time on his hands; his tenor banjo was parked up as sessions were off limits, and since moving to Cork city from Freemount, in north Cork, he’s long had an interest in the parks and the extant hardscrabble green spaces that somehow manage to survive urban encroachment and neglect.

Mick had been involved in restoring the local park on Grattan Hill where he lives with his family on the north side of the city centre. He knew what went into reclaiming a space for nature - and for people - the tidying and planting and fundraising, but above all the effort it takes to establish a community forged around a common idea.

Meanwhile, as the lockdowns wore on Mick could see on social media that people were a lot more entuned with their local environment.

“One thing I noticed was everyone is going around to their park taking pictures of all the trees coming into leaf,” Mick told me over the phone one Friday night this past July.

According to Cork City Council there are 44 parks and green spaces in the city, and Mick wanted to know what those parks were like. Back then, as he says, all he wanted was the data.

“I thought, ‘Look I haven’t a clue what’ll happen here, but if I put a tweet out maybe I’ll get five or six people to go around the city to take a look’”.

As he tells me, his bubble on Twitter - those he follows and who follow him - are “fairly green”.

“I don’t know them but we follow the same things.”

Their interests are biodiversity, nature and sustainability and they were the people who seeded Mick’s call out.

Mick says the interest was “unbelievable” and it led to a huge response, and with it all the headaches that go into communicating with an array of strangers on social media and on email threads, but he got a system going and then a spreadsheet, and that’s when he decided to start a rating system.

Social media can be many things, and many of those things tend to amplify the negative aspects of our increasingly digitised lives, but social media still has the power to connect people, and quickly, gathering them around a common goal. Mick’s call out - essentially a request for locals in Cork to inspect their parks - it went out fast and wide, and it was answered.

“Twitter was absolutely beneficial, it made it happen,” Mick says of reaching volunteer park surveyors. “And of course the lockdowns helped too.”

Cork parks

When you think of cities, parks are often one of the defining features we recall: Phoenix Park, Central Park, Hyde Park. By their definition parks are open and communal; they’re a relief from crowds and commercialisation. And if you live in a city centre, the park is effectively one of your only connections to nature, albeit one that is shaped around the city. And there is still something romantic about the city park, even if many of them don’t get the love they need or deserve.

Cork City Council manages and maintains about 1,500 acres of parks, walkways and open spaces. That includes The Lough, Fitzgerald Park, Tramore Valley Park, Bell’s Fields, Ballincollig Regional Park and many others. For the size and population of the second city, it’s not a massive land mass (1,500 acres is roughly about 800 GAA pitches). By comparison, in Belfast open spaces and parks constitute over 5,700 acres of the city, or about a quarter of the city’s total land mass.

What Mick wanted to arrive at, via the small army of volunteers and their data, was a comprehensive overview of these parks, which essentially belong to us all.

Or, to put it another way, as Mick says: “What makes a field up in Mayfield a park?”

On the face of it, that’s a fairly simple question, but it’s also, for want of a better adjective, an interesting question. As Mick says, what makes one field different to another field. If it’s a park, then what physical and natural characteristics does it have that qualifies it as a park? And in turn, what do we expect from it?

If you or I were asked what makes a park, it’s likely we’d arrive at a reasonably common set of answers: grass, plants, trees, benches, gates, swings, a playground, toilets, bins, paths, flowers, fauna, ponds, a basketball court, an outdoor gym. Perhaps even an enclosed space for dogs to run around.

And yes, perhaps a horsebox that sells tea, coffee and flat whites.

But, overlying all these factors is an essential one: community.

“It’s all down to community. The community needs to get active.” Mick thinks that one of the big reasons why some parks don’t live up to their potential is that they are missing this component, and without it, without them, parks suffer.

The categories

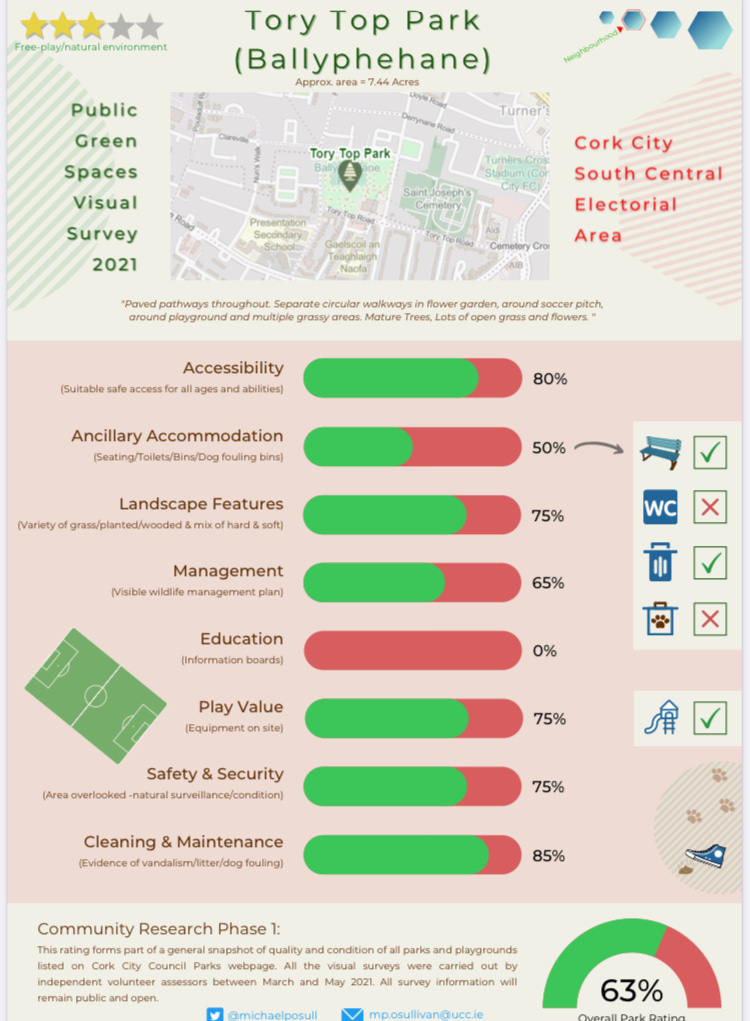

Between March and May of this year the park volunteers flooded into their local parks and armed with a survey Mick had cobbled together based on others he’d seen, they rated their local parks across eight categories that ranged from safety and security to education, play value and landscape features.

As the data trickled back, Mick, leaning on his background in graphics threaded it all together and the result is a detailed PDF that, were he a consultancy, he could charge a tidy sum for. (If you are new to Cork, or even you want to know more about a park in Cork, there is no better or detailed and jargon free park resource than Public Green Spaces, the website on to which Mick drafted all of the data he and the volunteers collected).

The best bits and the worst bits of each park are highlighted, and each park is given an over all rating. This past July, Mick released details of the data via Twitter building to a crescendo of Cork’s best park. I don’t think I’m spoiling it for anyone by telling you Fitzgerald’s Park came out on top scoring 90 per cent.

This is what the Fitzgerald’s Park volunteer had to say about the park:

"One of the City's flagship open public spaces. The park still retains a mix of formality and romance, with trim geometric flower beds contrasting with winding wooded paths - trees slant over a riverbank that is dotted with haphazard plantings of bulbs and herbaceous perennials, while a pristine rose garden is a riot of colour in June and July.''

That summation covers a fair bit of ground in less than a hundred words, but what blossoms in that description is a sense of pride in the park. Here’s someone who’s witnessed Fitzgerald’s Park in all seasons and walked its paths regularly.

The ratings game

In some ways you could argue Mick’s charts, maps and graphs don’t tell us much we didn’t already know. We have some wonderful parks - Ballincollig Regional Park with its wild flower meadows and meditation gardens take a bow - but we also have others that deserve their poor ratings. And our parks often lack important basic facilities.

Take for instance public toilets: from the 44 parks Mick surveyed only two - Fitzgerald’s Park and Tramore Valley Park - have public toilets. (The toilet at Ballincollig Regional Park was and still is at the time of writing out of action).

Also, the overall ratings for the parks on the north side of the city faired poorer in comparison with those for the rest of the city.

But, the power of what Mick has created is that you can’t argue against the data, and more importantly you can act on what that data shows is lacking or missing or where it’s falling down.

Mick is blunt in his assessment, and he’s not playing a points scoring game: “Some of the areas have very bad ratings, but they’re super areas to go, they just have no facilities.

“I’m not saying there should be a toilet in every park, but there should definitely be a few more toilets in some of them. I am saying there should be a bin in every park. And I definitely think there should be dog poop facilities in every park, absolutely.”

“Some parks have no benches, loads of parks have no education. There’s nothing to tell you about birds.”

Accessibility is also another massive issue Mick says, highlighting Bell’s Field, which, as the volunteer highlighted has “one of the best green open spaces to enjoy views of the western skyline.”

“It’s a super spot, but like there’s no investment in it. There’s one tree there, there’s a bit of grass, a couple of benches and a couple of gates,” says Mick.

The park rates poorly on accessibility, 35%, and dismal on education 0% (signage). This is all the more tragic when you consider that The Metropole Hotel lists Bell’s Fields as one the seven must-see “Young Offenders” filming locations.

Another problem Mick’s volunteers highlighted was the use of pesticides such as glyphosate, either by the City Council or by subcontractors which Tripe+Drisheen highlighted earlier this year. Play areas for children older than six or seven is an another area that needs to be improved on, according to the data the volunteers collected.

Mick has shared the data with local councillors, TDs and the city council (he’d love to be able to present it in a physical format) and he plans to come back to the project next year and in subsequent years, either by himself or with volunteers to survey the parks, and see what if anything has changed.

“And then in four or five years time it would be great to say, ‘Well, look we have 15 new park groups and hopefully there’ll be a network’”.

Mick’s biggest fear, and this also informs why he has undertaken the project, is that as the city densifies some of these green spaces and parks could be co-opted for commercial reasons.

The way Mick sees it is that if “there’s no park groups to advocate for the open spaces why wouldn’t they build on it?”

His fears are not unfounded: Look at what’s unfolding in the Marina Park where the GAA are seeking to build a car park on Cork City Council land, which is zoned for Open Public Space.

The “10-minute city”

If Mick were Lord Mayor of Cork City, you get the sense that trees and parks would be to the forefront of his agenda. (Cycle lanes too, and toilets).

“Every child, every older person, every disabled person in our community should have access to a green area,” Mick says. Especially if we’re going to have apartment living, “and we should have apartment living.”

“You have to have your parks and you have to have your open spaces.”

The City Council thinks as much, at least on a policy level. This past July it released the draft plan outlining the city’s green and blue infrastructure (GBI), which runs to nearly 400 pages, and describes the interventions Cork city is planning to take in the face of urban growth and the climate crisis.

According to the report:

Green and blue infrastructure (GBI) forms a cornerstone of sustainable development. Increasingly recognised as a ‘must have’ rather than a 'nice to have', it offers multiple economic, social and environmental benefits.

One of those benefits are parks and green spaces, which *jargon alert* the report identifies as “healthy spaces”. (Shops, cafes, restaurants are identified as “economic spaces”).

The plan, and bear in mind this is still only in the draft stage, sets out an idea for Cork to be developed around a network of 10-minute cities. This is even more ambitious than the “15-minute city” which gained a lot of currency during the pandemic, when people were restricted to their localities and their eyes were opened to the full extent of what their local area offered. Or lacked.

Key aspects of the 10-minute city concept are (and this is all via the City Council’s GBI draft plan): more trees and plants; safe and attractive streets; making it easier to walk, cycle and that we become less reliant on cars; ensuring access to parks and green spaces close to your own home.

These are all laudable and “must have” goals, but one of the key challenges is how to get there, especially in a city that frankly sucks when it comes to enforcement (see the so-called Pana ban, dereliction levies, parking on footpaths).

Making a local park

When Mick moved to Grattan Hill in 2012 he wanted a nearby green space that he could bring his young family to.

And there was one - Grattan Hill Park, or Railway Park - just down the hill from his house towards Kent Station (well within ten minutes of his front door). The problem was that over the years it had been neglected, filled with litter, cans and needles, and it was sometimes used by drug users.

Mick and a group of locals banded together and focused their attention on returning the park to the community. There’s a tendency here to give this the Hollywood story arc with shots of smiling kids and parents armed with brushes and shovels, and while there was some of that, there was also countless meetings with the city council, with the police, local TDs and councillors.

In time the neighbourhood restored the park and they fundraised by themselves (Mick says they were some of the best nights they had as a community) and they’ve subsequently planted pear and apple trees around the neighbourhood and that park has become a cornerstone of the community.

“It’s a great place to learn how to cycle a bike along where the old train tracks used to be,” says Mick. Someone else put up a basketball stand and now kids can play with that. “It’s a community park,” he says.

Mick recognises that they haven’t solved the underlying social problems, “I worry we just moved it on.”

“But if we didn’t have that little spot we’d have to go over to Shalom Park, about a twenty-minute walk, or up into the Glen which is another twenty-minute walk and that ain’t easy with a buggy.”

More, not fewer benches

Earlier this week Padraig Rice pointed out on Twitter that benches (likely on most people’s list of what should be in a park of green space) had been removed from Connaught Avenue, calling it “another act of public vandalism” and laying the blame with Cork City Council.

(They did in fact remove the benches at the request of councillors who had been contacted by some local residents who didn’t want to deal with disturbances generated by people gathering there at night).

As with any thing with a whiff on controversy on social media, there was a pile on and sorting out the facts from the indignation, well you know what that’s like.

And so I thought I’d give Mick a call and get his take on it.

“Benches,” he says, “are not the problem.”

“The temptation is always there to remove stuff,” Mick says. “We have a serious problem if we’re taking away benches because of anti-social behaviour."

Mick explained that when they wanted to restore Grattan Hill Park to the community, they as a community went to the Gardaí and asked specifically what they should be doing.

“We met with the Community Guards and we asked them what is our best course of action, how do we stop people coming in here taking heroin?”

The immediate answer was enforcement: and so the Railway Park group agreed that if there were groups congregating in the park, drinking or taking drugs they would call the Gardaí straight away.

“We agreed to deal with it straight away, to not let it go on. And some days were better than others, the cops were down in twenty minutes, and some days they didn’t come at all.”

But you have to be persistent and you have to have a plan Mick says, and the plan is ‘Look, the Gardaí are in charge of law and order, you have to let it to them.”

And the second part of that plan was “to work away at making the park a nicer place.”

Which is why for Connaught Avenue Mick thinks maybe more benches are the solution, and a play area for kids and to make it a place where the community will gather.

Mick also recognises that in resolving one problem, there are still underlying structural problems, pointing out that drug users are out in the open because we don’t have needle clinics.

“We want a park,” Mick says, “but we also want a place for people to recover. It’s a breakdown in services a lot of the time.”

Essentially what Mick O’Sullivan wants to build are communities, lots of them, centred around nature - a place for plants, trees and people.

A volunteer speaks

Marica Cassarino was one of the 31 volunteers who answered Mick’s call out to survey her local park.

“I got involved in Mick’s project early in March 2021 to assess two parks that are very close to my house: Ballybrack Woods (The Mangala) and the Douglas Community Park. I completed the assessment together with my five-year-old boy, who really enjoyed taking photos and getting to do something new during our usual walk through the two parks.

We took part in the project because I felt that it would be a good opportunity to share with others what amazing amenities our local green areas are. Both parks provide a space where to walk and cycle safely, be in contact with nature, meet friends and have fun. They are the go-to place in the community not only for leisure reasons, but also because they provide a beautiful alternative route to access Douglas village from the surrounding areas in an accessible way and away from motor traffic.

They also give you variety: one is wild, giving you a full immersion in nature, while the other is a typical urban park with a playground, exercise facilities and coffee places. When we walk or cycle there, we meet other residents, and we feel part of the community.

During the pandemic, having both parks within our two kilometre radius made a significant difference to us in terms of activities that we could do outside of our home, and contributed to maintain our mental sanity as a family with a small child. The Ballybrack Woods became our “back garden”, full of hidden places to discover and play in. I felt that footfall in the parks increased considerably during lockdown, which speaks to me to the potential that green spaces (or their absence) have to make (or break) the wellbeing of a community.

Taking part in Mick’s project helped us to appreciate even more all the amenities available to us in these two parks, while also highlighting what may be improved from our perspective. Both areas are managed and monitored, accessible, with plenty of opportunities for play (formal and informal). Littering and dog fouling are an ongoing problem, particularly in the Ballybrack Woods, which could do with more bins and tackling of group drinking.

However, the Douglas Park has recently undergone major changes related to the flood scheme, which have brought an increase in number of benches and bins, a beautiful new path and overall an improved atmosphere. In Ballybrack Woods, new information boards were installed a couple of weeks ago, which give you a sense of its history and wildlife; fascinating for kids and grown-ups.

I feel lucky to live near such good examples of urban parks, and I was delighted to contribute to making the public more aware of the beautiful outdoor locations we have in Cork City. The project was also an excellent example of grassroot citizen science initiative, of which I would love to see more in Cork. Hopefully the project will promote a conversation about green spaces in Cork and how important it is to protect and cherish them for the welfare of the community.”

Loved this article, the local parks here were a lifesaver for so many people during lockdown. Great to hear about other parks and green spaces, no matter the size

A great read jj hope it inspires more people to come together and improve their local green area or park and develop a community spirit leading to friendships and a safe and friendly place for their children to play and enjoy