Picketing in the Pandemic

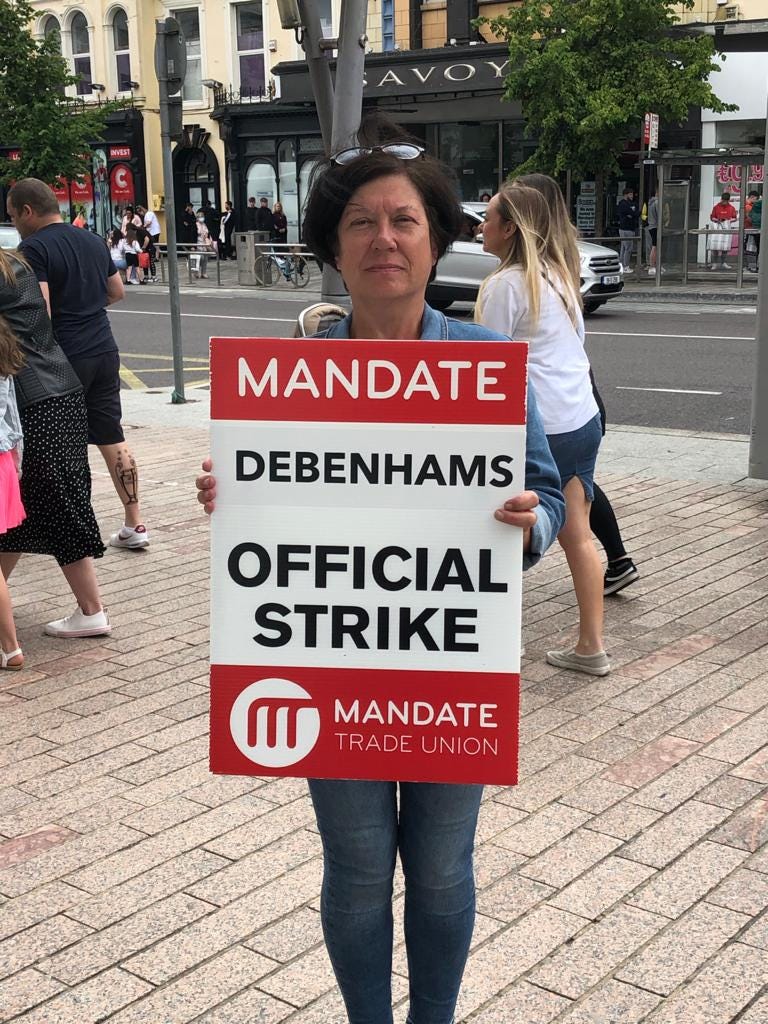

April 9 marks the one year anniversary since Debenhams cut and run from Cork. Valerie Conlon and her colleagues have picketed nearly every week since.

This is it how it ended:

Shortly before midday on Holy Thursday, 2020, in the second week of the first lockdown, Valerie Conlon was on the phone in her car returning home from shopping, her husband at the wheel, when she noticed an email from her employer, Debenhams Retail Ltd.

As Valerie tapped open the email her husband slowed down and pulled up to a Garda checkpoint by Five Mile Inn in Ballinhassig.

“With great sadness,” the email announced, Debenhams was going into liquidation.

“Sweet Jesus Christ,” Valerie remembers saying to her husband and the Garda.

“I’m after losing my job.”

Both of them just looked at her, before the Garda eventually waved them through.

April 9, 2021 marks the first anniversary since Valerie and nearly 2,000 of her Debenhams colleagues across Ireland lost their jobs when the British retailer suddenly pulled the plug on its Irish operation. In the year since the Irish exit, it has also ceased trading in the UK. Over 300 employees lost their jobs at the two Debenhams stores in Cork.

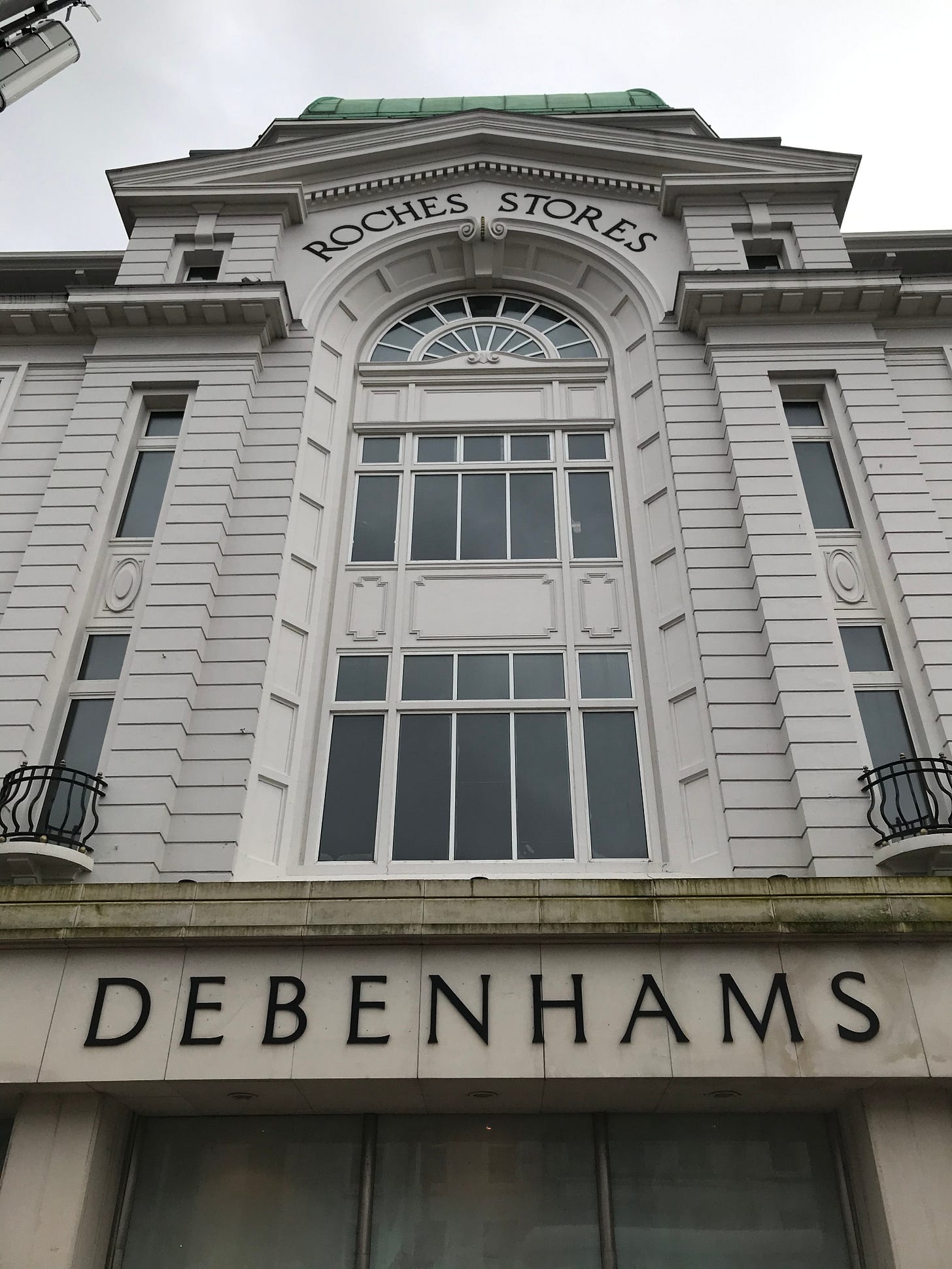

This month will also mark the first anniversary since Valerie and her former colleagues took up their placards and began picketing outside the Debenhams on Patrick’s Street, the site of the old Roches Stores building, fighting against their former employer, which cut and run, and the Irish government which they believe has left them down.

And they’ve continued that protest, organizing pickets and sit-ins through a year-long pandemic, three lockdowns and in “very, very hard times,” Valerie says.

Six degrees of separation

Like many of the others on the picket line at Patrick’s Street, Valerie’s tenure predates Debenhams entry to Ireland in 2006. Before she was made redundant by email, she’d put in 24 years, first at Roches Stores and then at Debenhams when they took over.

It’s hard to overstate how big a role Roches Stores, which was founded in Cork in the early 1900s, played in the fabric of the second city: everybody and their mother went through there, in fact readers of a certain age probably went through there with their mothers, dragged through, in search of socks, curtains, pots, pans, communion, confirmation and wedding rigouts, tights, fruit, vegetables, meat, fish and sundries.

In the era that Roches ruled you could play six degrees of separation (from Roches) and probably find dozens of connections within one or two degrees: people who worked there, or whose mam or uncle worked there, who had a part-time job there, who robbed something from Roches, and those shoppers who “swore by Roches.” This was Cork’s hundred plus years relationship with Roches.

“When I started in Roches I worked in ladies’ and children’s shoes, so I would have been trained to fit children,” Valerie, 56, tells me over the phone. Ironically, children’s shoes have become a flashpoint in the current lockdown as up until this month shoes have only been available to buy online. As many a parent will testify out loud and often, the internet does not make a good shoe-size fitter.

Valerie, a shop steward with the union MANDATE, has fond, but not rose-tinted, memories of working in Roches and Debenhams.

“We all give out about work, we all give out about the fact that we hate going in there. But I actually enjoyed it,” she says.

“You’d go in and meet up with the girls and you’d have a good chat with them and even the customers coming in, you’d have a good chat with them, you’d have a laugh.”

There were other aspects about work that Valerie liked: for the past eight years she worked three days a week. She would park at her mother’s house in Turners Cross, walk in to work, and even at work, all the walking was a way of staying fit.

When Debenhams took over from Roches in 2006, Valerie says they fought hard for their rights and conditions, but they also worked with the new management. There were cosmetic changes: instead of sales assistants they became sales advisors - “What’s the difference? None of us ever knew,” Valerie says - as well significant changes with the new owners. Some of the autonomy they had was dialed back or taken way and the staff canteen was closed.

In 2016, Debenhams was put into examinership and there were renegotiations and lay-offs, but the company came out the other side.

“We were told after that that everything was fine, even though England was having problems,” Valerie says. “We constantly asked them, ‘Are we ok?’”

When the store closed in March 2020, in line with the closure of shops across the country during the first lockdown, Valerie was in constant contact with her own store manager, and “he was always coming back to me saying we were ok.”

Not even 24 hours before the fateful Holy Thursday email, workers were notified on Ash Wednesday to say everything was ok. Clearly, however, everything was as far away from ok as it could possibly be.

Picketing in a pandemic

Strikes are generally won and lost on two fronts: public support and the commitment of the strikers. What makes striking in the pandemic so odd is that there are people who have not been into the city centre for 12 months or more. In fact, there might even be people who have not been into a clothes shop since last year. If they have seen the strikers, it might only have been in a fleeting image online or on TV.

Picketing and protesting is tricky at the best of times, given that there are so many moving parts and so much emotion, but doing it during a pandemic? That was new terrain.

Workers organised online - their WhatsApp group came to be known as “Picket Pals” - and within a week they were on Patrick’s Street doing a socially-distanced protest once a week until they voted to strike.

Up until Christmas Valerie was picketing three days a week. When Level 5 restrictions were reintroduced at the beginning of 2021, she cut back to every Wednesday and Friday.

Before Christmas the strikers were putting in three shifts of five hours each, starting at 6 a.m. Since January they’ve cut the shifts down to three hour slots, with crews organized online to fill in when needed.

Valerie admits that with the reintroduction of the third lockdown the strikers have become even less visible, especially when the city centre is so depleted and empty. There were times I passed the Patrick’s Street entrance in the cold months of January and February and the famous building, constructed after the burning of Cork 100 years ago, was a forlorn and hopeless sight. At times the handful of strikers picket outside an empty building on a virtually empty street.

Still though, Valerie says they have had constant support, such as the man who comes weekly with a Lotto ticket for the strikers.

“We do still have a lot of support. Probably it’s not as strong as it was because people are obviously getting tired and you can’t blame them. They’re getting tired of listening to us, I suppose, especially to me, but I have to say the support is still very strong out there.”

Donnchadh Ó Laoghaire, Sinn Féin TD for Cork South Central, said the “workers deserve enormous credit for their steadfast commitment and determination.”

“They have been inspirational and the people of Cork are right behind them, one year on.”

Just as strikes bring out the best in people, the opposite is equally true: twice the large sign hung across the front entrance of Debenhams that reads “The Taoiseach has left us down badly” has been removed. Valerie reported the theft to the Gardaí.

She recalls the first time they ordered a replacement, the sign-maker told them “not to give in, keep fighting.” He also offered the replacement sign for free.

Words of encouragement like those are a good place to reassess what Valerie and her colleagues are fighting for.

“Debenhams have walked away,” Valerie says, so the fight really is with the Government - hence the sign - and it’s a battle on two fronts.

First, the former workers are demanding they be compensated according to the “2 + 2” agreement. Essentially, this is four weeks’ pay per year of service, made up of two weeks’ statutory plus two weeks as per the understanding between Debenhams and their workers.

When a company goes bust, it becomes a question of who gets what, and also just as importantly, who is prioritised. Valerie and the strikers clearly think it’s not them.

This, from Kitty Holland in the Irish Times is a good summary of the sorry situation:

Under the 2014 Companies Act, when a business goes into liquidation its employees are on a list of creditors coming in after Revenue and the Department of Social Protection. Debenhams is understood to have owed these first creditors €18 million. The workers argued Debenhams Ireland had assets in its stock and fixtures that could be used towards honouring its commitments to staff.

Mick Barry, Solidarity TD for Cork North Central, told Tripe +Drisheen that there are two key issues at stake, one being that the Government should ensure the four weeks of redundancy are paid and that they should “go after Debenhams to fund the extra two weeks.”

“And secondly that the Government would introduce legislation to protect workers’ rights in liquidation situations,” Mick says. “Those are the two key demands that I’m focused on.”

“Five years ago, we were told Clerys workers were the last group of workers who would be affected in this way. Then we were told it was the Debenhams workers and now it’s after happening to the Arcadia workers,” he says.

He’s also calling on trade unions to “step up to the mark and increase the pressure on the Government to legislate now to improve workers rights in a liquidation situation.”

Donnchadh Ó Laoghaire said that the Government should be “doing much more” for the Debenhams workers.

“The legislation is clearly not fit for purpose and is open to abuse by unscrupulous companies, such as has happened often in the past and yet successive governments did not act to prevent this,” Donnchadh told Tripe + Drisheen by email.

“It is still possible for Government to play a role, by reform of the insolvency fund and changes in legislation but they have been inflexible and refused to budge. I think that is not good enough.”

The workers want the €3m the Government has aside for retraining to be converted into cash, a proposal which Mick supports.

“People need to pay their bills and mortgages, and upskilling isn’t going to do that for them,” Valerie says.

Like many of those made redundant Valerie, has already signed on for a training course, in administration, which was offered for free and with a laptop for the duration of a course.

Why not move on with your life?

When I ask Valerie - a question many of us may have asked ourselves - “why keep going?” - she tells me she’s heard the question often.

“It’s very hard to spend nearly a year out fighting for something and just to turn your back on it,” she says. “We’re also fighting for the legislation to come in. Even though people might be giving out about us now doing this, but it’s their children that we are fighting for in the future. We’re too late, but it’s for the people behind us.”

As Valerie points out, she and her colleagues have paid for their redundancy week in, week out with the money that came out of their salary.

“The Government have’t put their hands deep in their pockets and paid our redundancy. We paid for our own redundancy and we’re just asking for it to be topped up like we had for our agreement in 2016,” she says.

In our conversation Valerie generally sounds more resigned than angry. It’s also worth pointing out that in a year when she and her colleagues lost their jobs, they also had the business of getting on with life in the pandemic. Just as everyone else did.

Valerie’s husband lost his job. Her son was diagnosed with cancer, but has thankfully since got the all clear, and her mother died earlier this year in a care home.

As she says, it’s been tough for everyone.

But where Valerie’s anger does come through, it’s directed at the coalition Government.

“Debenhams have walked away,” she says, and such is the story of capitalism, but when it comes to politics, Valerie has power.

“My political stance has really changed,” she says. “I will never vote Fianna Fail, Fine Gael or the Greens in again. I will be looking at my ballot very, very carefully the next time because I am very angry with the Government at the moment.”

“I can’t wait for the next election because I will have my picket sign inside the door and when they knock at my door that’s what I’ll be bringing out.”

Valerie is also critical of politicians from the coalition parties who turned up early on for their “photo op” with the strikers: “We haven’t seen them since they got their positions in Government.”

Whatever you say, say nothing

When Debenhams closed in line with restrictions enacted during the first lockdown, Valerie and her colleagues expected to return to work when shops reopened.

However, apart from a brief spell when they staged a sit-in last September, they have not been allowed back in the store, which means they also haven’t been able to return and collect belongings and personal items from their lockers.

“All my belongings are in there in the locker,” Valerie says, explaining that she also has some sensitive material in there, owing to her position in the union.

Valerie says she was of the understanding that KPMG, who are handling the liquidation, were arranging to have the lockers cleared and belongings placed in plastic bags. But nothing has come of that yet.

Valerie contacted KPMG officials to say she has no problem with being escorted by a Garda to her locker while being monitored, she feels so strongly about it.

I contacted KPMG for information and comment about this point, which is, on the face of it, not the most complex issue to resolve.

KPMG didn’t reply.

So I tried again:

I am writing a story about the former workers of Debenhams in Cork (Patrick’s St branch) and I was wondering if you would be able to tell me when/if the former workers will be able to access their belongings in (their) lockers, and how this might happen?

And this is what KPMG, who have an office on South Mall where they employ 190 people, eventually say:

No comment.

Bear in mind, the KMPG office is about two minutes walk from Debenhams.

So I ask Mick Barry what he thinks of KPMG’s silence.

KPMG's stubborn refusal to allow Debenhams workers at Patrick’s Street reclaim personal belongings from their lockers is mean and petty in the extreme. It's actually a pretty good symbolic example of how they have dealt with a group of working women who have dared to challenge them over the last 12 months.

Donnchadh Ó Laoghaire echoed Mick Barry’s criticism saying that the Debenhams workers have “been extremely badly treated by the liquidator, KPMG.”

They (KPMG) “have been, in my view, deaf to their concerns, and failed to treat their possessions or their entitlements with respect, they should be given access to their lockers, but they should have also made an offer to the workers that properly reflected their time worked and what had been promised to them.

Perhaps officials at KMPG might consider if the shoe was on the other foot, if they were locked out of their workplace for over a year unable to retrieve their belongings, what they would think then. Perhaps that might instill comment.

Contrast the silence from KPMG with the picketers’ relationship with the Gardaí, which Valerie says has been great.

She recounts how one Garda called her frequently to check in and see if they were being treated well; they’ve been understanding too when picketers were passing through checkpoints to and from picket duty.

“I have to say we do have a very good relationship with the Guards” Valerie says.

Life on the picket line

On the picket line, Valerie has come to see different aspects of her former colleagues: “Some of the workers who would have always been the quieter ones have found their voice. You’re seeing different personalities in what you would have seen when you were working with them.”

When Valerie’s mother died in February, co-workers “were just amazing,” she says.

Once a week a rota is made out and shared on their WhatsApp group; it needs to be flexible to accommodate the changing nature of the pandemic and to account for everything from homeschooling children to looking after elderly parents.

The core group of 40 are also supported by ex-Debenham workers who have found employment elsewhere: they come in on their day off and picket to show their solidarity, including staff from the Mahon Point branch which has had all of its stock cleared out.

At the outset I wrote about how the Roches Stores building loomed large over Cork; half the time, if you were on Patrick’s Street, Roches - and then Debenhams - was the reason you were on “Pana”.

For Valerie, picketing outside the building where she worked for 24 years, and where deep down she knows she never will again, is a strange feeling. All the more so because of the sorry state of the building.

“It’s awful to look at,” Valerie says. “You’re on Patrick’s Street and you look up at the building and it's such a beautiful building. And it’s empty.”

“You would wonder: what’s going to go into it?”

“We would like something to open in there. It’s been such a big part of our lives, it would be awful to leave it empty.”

A very honest and heart felt account of an awful year especially for Val. She should be very proud of herself and I was very fortunate to have worked with a great group of people that I am honoured to call my friends ❤❤

Valerie is such an inspiration to everyone that knows her, to show such strength and courage in such a difficult year but to never give up, she makes us all proud to stand beside her on the picket. Well said Val 💪