Memories of Flowers

In Ballydehob, the enormous photographic archive of a London photographer who holidayed in West Cork raises questions about memories and loss; about what we keep, and what we let go.

Where do we start, when something is so vast?

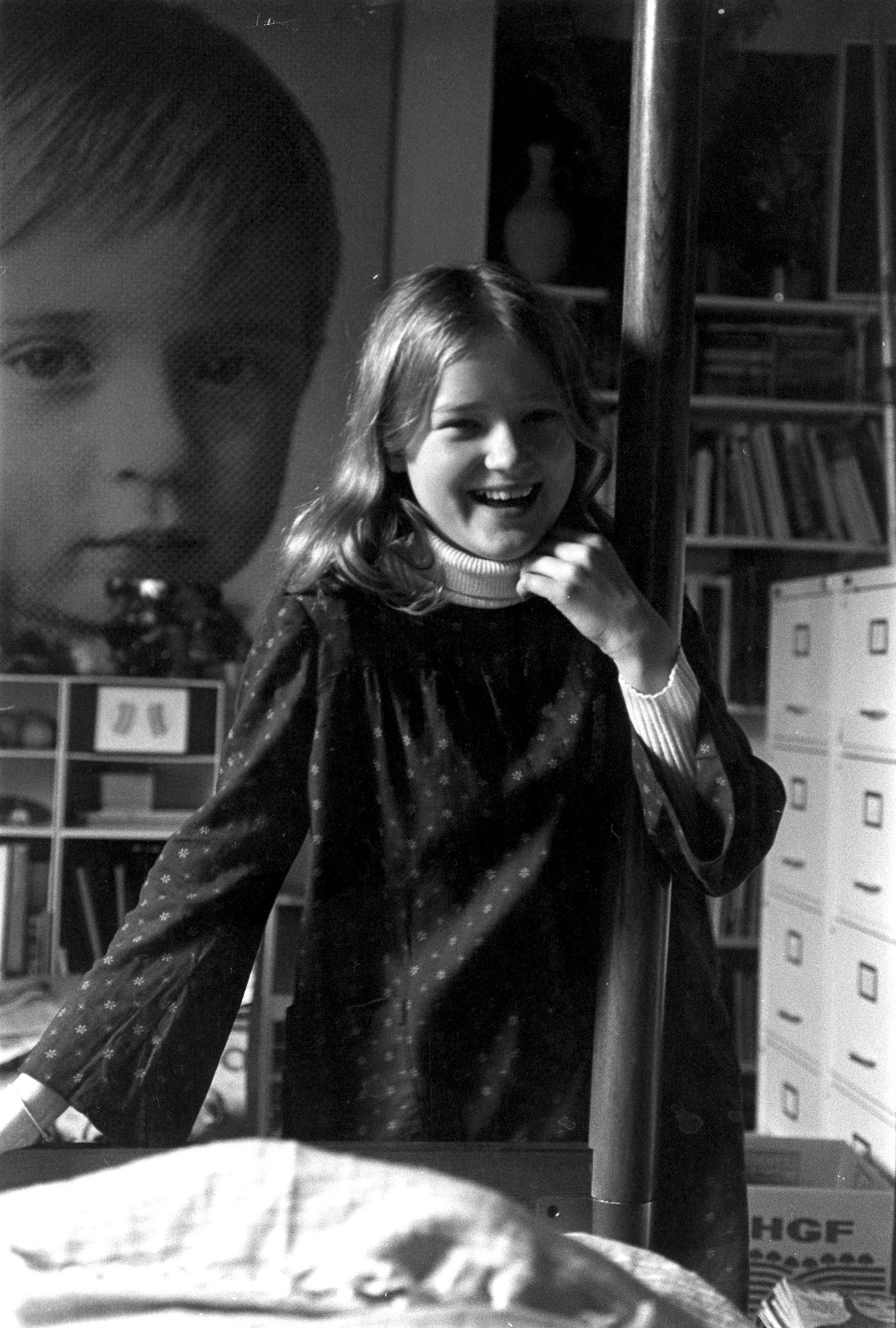

We might as well start with one black and white snapshot of a laughing girl. She’s hanging onto the post of a four-poster bed. Behind her, there’s a portrait of another child. And there’s a set of filing cabinets.

“I’d say I was about ten or eleven there,” Francesca Flowers says, smiling. “I think I was taking pictures of my dad and my step-mum, and then they took a picture of me. That was actually their bedroom.” She pauses. “I look happy enough.”

The little boy in the portrait behind 11-year-old Francesca is her eldest brother, Adam, she tells me.

“My dad had it blown up really large with a dot-screen filter. I went to visit my brother recently, and he’s got the print hanging in his house. It really is enormous.”

Francesca is the youngest child of photographer Adrian Flowers, who ran a photographic studio in Chelsea for decades, photographing stars of the swinging sixties including Twiggy, Michael Caine, Vanessa Redgrave and Alec Guinness, but also forging a strikingly successful career in advertising work and editorials for magazines including The Observer.

Francesca is standing in front of some filing cabinets while we talk, in the house on Ballydehob’s main street that she’s renovating with her partner, the former director of the Crawford Art Gallery, Peter Murray.

They may even be the same ones as those in the black and white photo we are looking at.

These cabinets, and others, contain an estimated 250,000 negatives, transparencies and prints amassed during her father’s career. And now, it’s Francesca’s self-imposed task to set about ordering this enormous and impressive archive.

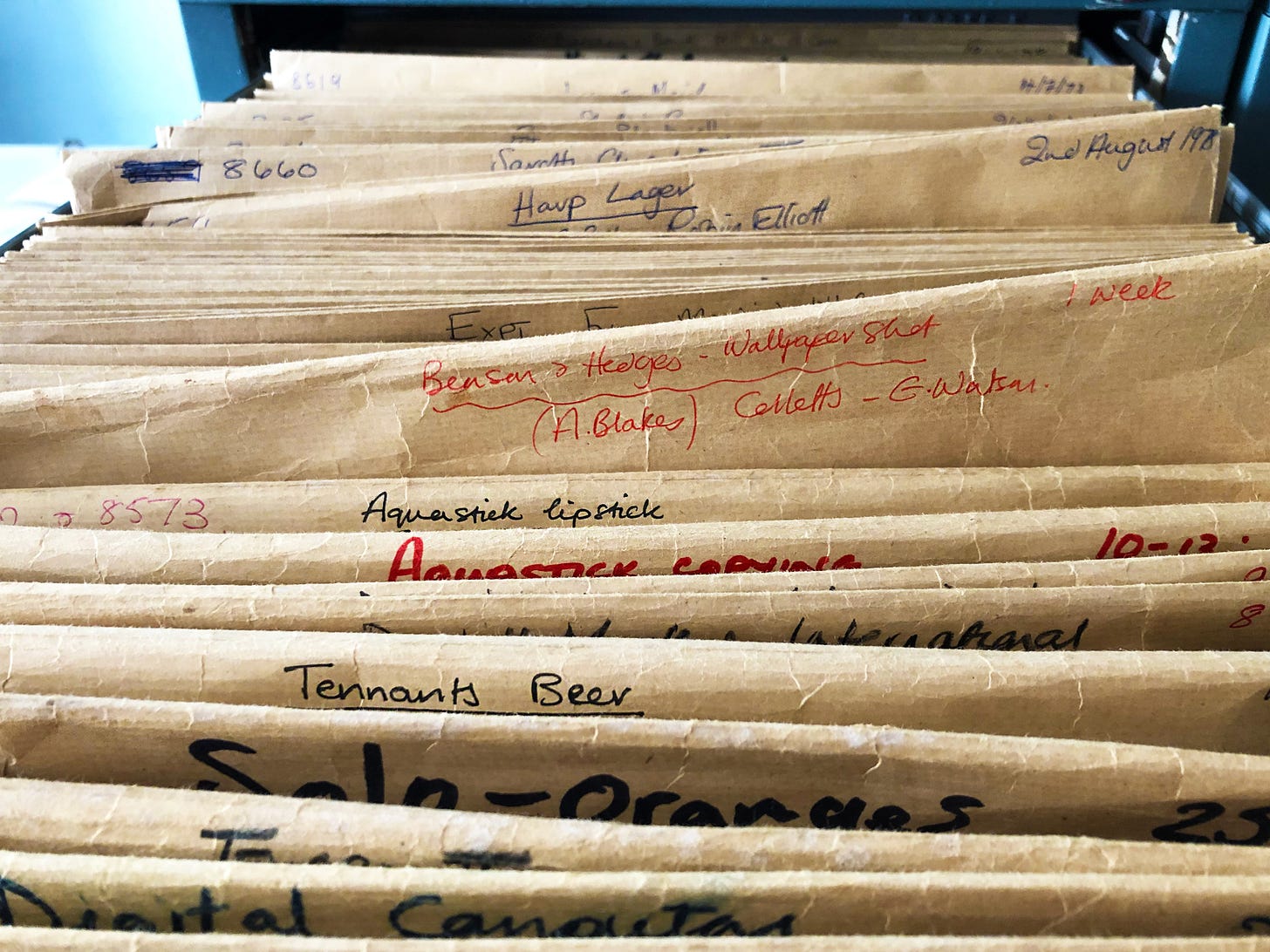

Working from the contents of the filing cabinets, which contain brown A4 envelopes, each one labelled with a “job number” and containing a varying number of negatives or transparencies, sometimes also polaroids of lighting set-ups, as well as yellow “job cards” with a corresponding number and detailed description, Francesca has been making a digital index of the collection on an Excel spreadsheet.

“I get a pile of envelopes and input them into the spreadsheet, and if there’s missing information I have to go to the job cards,” she says. “I try to include as much information as possible: art director, client etcetera. So that’s a very big job in itself.”

“And sometimes I can only find a print and no neg, or worse still I find the envelope is missing. That can be frustrating.”

Francesca estimates that she’s catalogued slightly less than a quarter of the “jobs” so far.

Although they’re called “jobs,” Adrian didn’t only catalogue and number his commercial studio work, but also his own more creative or experimental work, as well as personal photos of family, or his beloved little dog.

He was particularly driven to document and archive and methodically store his work.

“Whether it was what he would call an experimental or non-experimental job, every single one would have a number and it didn’t matter if that was family or personal stuff: it all got a number,” Francesca says. “That’s quite organised.”

Vinegar syndrome

Many of the negatives are now emitting a tell-tale vinegary odour known as vinegar syndrome. If anything, this makes the work of digitising the archive even more urgent: connected to problems with fixing, vinegar syndrome is the release of acetic gas from the acetate film.

As the gas is released, over time, the emulsion layer of the film, the part that holds the image, will decay and the image will be lost. It will fade from memory.

The stuff merchant

Adrian Flowers died in 2016, at 89 years of age. He had suffered from Alzheimer's towards the end, and had been in a care home for the final year of his life.

He moved to Lot-et-Garonne in South-western France in the nineties, where a vast barn alongside the house he shared with his second wife, Françoise, contained what he referred to as his “stuff:” not only his negatives and paperwork, but a vast array of props and knick-knacks.

“It’s such a contradiction, but he was quite fanatical about keeping things, and could also be quite disorganised,” Francesca says. “The essence of this archive of 12 filing cabinets was just a speck compared to this enormous barn where he kept everything: all his props, everything from his studio.”

Adrian’s amassing of stuff went beyond just absent-mindedly hanging on to things: he would often photocopy his own part of a correspondence before sending a letter, meaning he retained a full record of an exchange.

“I think he had a fear of losing stuff,” Francesca says. “He would copy everything, even sometimes copy prints onto photocopier paper which was then glossy finish, like fax paper.”

“In the barn, there were these containers everywhere, like as though you could put things in a box, control what was happening to them. As though they could contain all your thoughts.”

“He always had notebooks in his pocket and of course that was a memory aid as well. He wasn’t diagnosed with Alzheimer’s until quite late on, but he could have had it for some time.”

On owning the moment, and on memory

Is it a terrible irony that Adrian Flowers would lose his memory at the end of his life, or was his drive to document everything so completely a touch of prescience?

Either way, metaphors abound surrounding memory loss and his archive: fading negatives, fading memories. Filing cabinets with some contents missing. The erasure of vinegar syndrome.

“He was getting bad around 2012, and by bad, I mean he was just doing strange things and starting to be forgetful,” Francesca says.

Francesca did a Masters at Canterbury Christ Church University in 2018, two years after her father’s death: its title was My Father, My Self: A Reflection on the Photography Archive of Adrian Flowers. It was a catharsis, she says: a way of confronting her father’s death but also some very strong themes.

“It became a much more personal study, really to do with memory, and loss and Alzheimer’s and chaos,” she says.

A childhood in front of the lens

Francesca describes a childhood that wasn’t without its difficulties. Adrian had married her mother, Angela, when Angela was just 19. The couple had four children, three boys and then Francesca, but split when their youngest was seven: while her brothers lived with their father, Francesca lived with her mum and her mum’s new partner.

Adrian would later marry again, but didn’t have children with his second wife, with whom he stayed until his death. Francesca’s parents were energetic, creative, but frequently career-driven.

“My mother was starting her own art gallery from the time that I was six,” Francesca says. And her father was very hard-working and focussed on his work.

One way that Francesca could ensure she was the focus was to position herself in front of her father’s camera.

“I think the studio represented some sort of stability for me because my parents divorced when I was seven,” she says.

“I don’t remember them together, probably because my dad was at work. I loved the studio. He had this little wooden train that must have been a prop from something and I’d go whizzing around on it. It wasn’t a large studio: it was a converted house, really. He had a very high atrium where he could have his 10-8 camera up on a tower, with a balcony.”

“I really enjoyed being photographed: there are plenty of photos of all of us children but I suppose I was his only daughter and I think he found that quite interesting after three sons. I would just go into his studio and say, ‘I’m here, take photographs of me.’ Any opportunity, to get in the studio and be photographed.”

“I remember I bought this Biba outfit and I was clad from head to foot in purple, and his assistants did my hair and nails and I was like, this is my big moment. Probably because I knew he was photographing models. It sounds very precocious, but really I was quite a shy and painful child. I definitely would have been vying for some attention there.”

Having spent some time in boarding school in her teens, Francesca moved to Australia at 19, returned to London and spent a year working in her father’s studio doing colour processing, worked in TV for a time. Later, at 30, she would attend University to study not photography, but music: a cellist and pianist, she plays with several well-known West Cork musicians including Tess Leak and Susan McManamon.

“The archive is wonderful but it’s kind of tough going, and the music just keeps things balanced,” she says.

Photographs as proof

Photos aren’t proof, Francesca, more than anyone, knows. A photographer chooses their frame and their moment, engineers and orchestrates. But we live in a world where photos are frequently seen as representing truth, as evidence that something has happened.

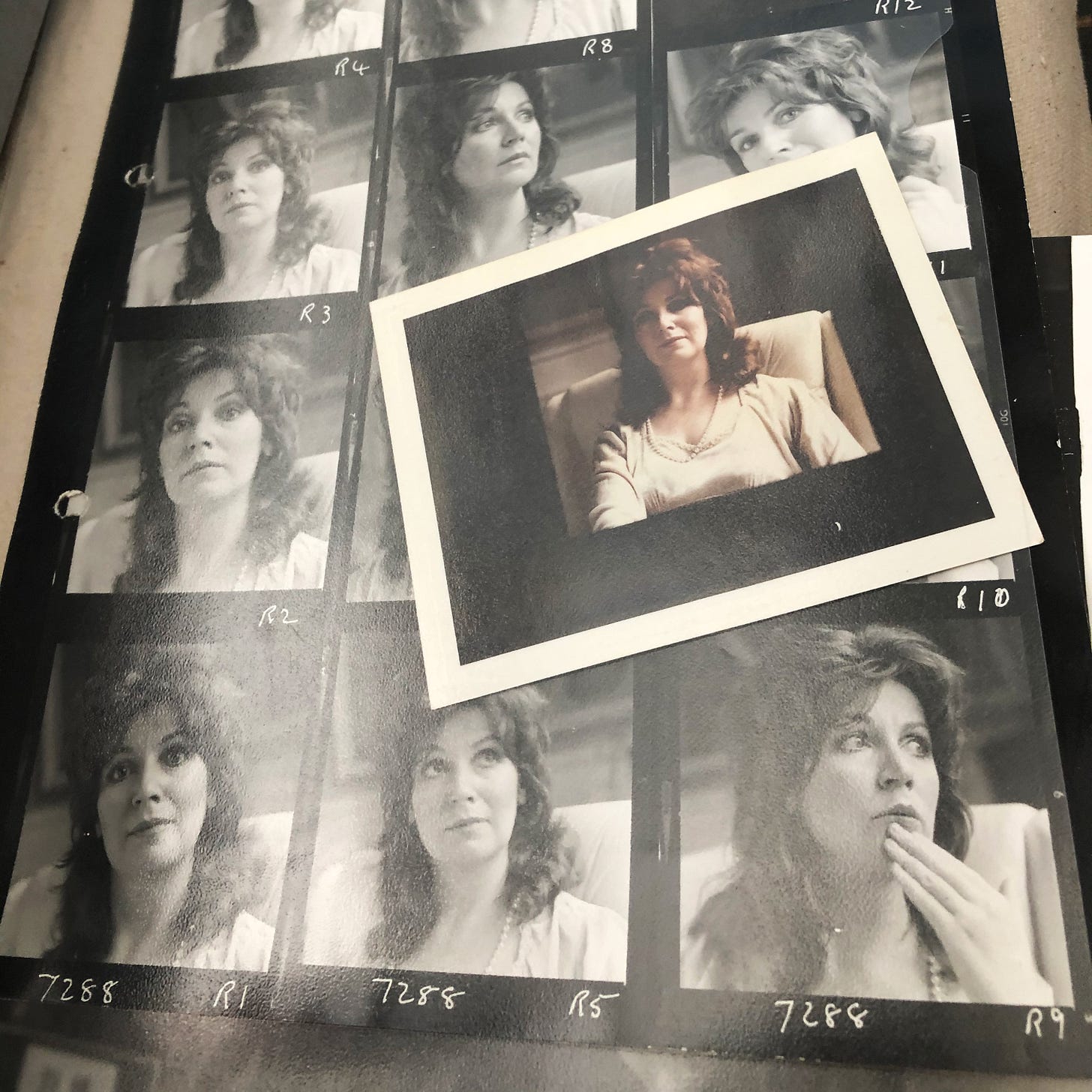

Adrian Flowers was renowned for his technical abilities, pre-Photoshop, to stage elaborate, fantastical set-ups for commercial work: Benson & Hedges ad campaigns, Kit Kat ads, many requiring composite images or large props to achieve. Many of these are far more in the Pictorialist tradition, where photography was seen as a tool to achieve an artistic effect, than an attempt at documenting the real.

“That’s the thing about photographs: they’re proof, and then they’re not,” Francesca says. “You think because they exist, it’s proof that something happened, and that’s really complicated. It’s not only to do with trickery: if someone is smiling in a photo, are they really happy? How do you know?”

Yet digging into her father’s archive and unearthing snapshots of her family intermingled with Adrian’s commercial work has been a revelation. There are echoes of an earlier life she doesn’t recall, not least amongst pictures of the family in Ireland.

Adrian and Francesca’s mum, Angela, acquired a holiday home in Rosscarbery in the fifties and there are many images of West Cork in the Flowers archive.

“I have early memories of being in Ireland,” Francesca says. “We spent every Easter and summer coming over. The family house is still here, and those years were very happy, mostly. I have bitter-sweet memories, mixed memories, but overall very good.”

“I found all these very happy shots of me as a baby, doing things with my mum, all of us laughing together. So I wrote about it in my thesis. A baby can’t pretend to be happy, surely? There was genuine happiness in those photographs.”

“That was a real revelation to me, because I had convinced myself that I had been a bit unhappy and I didn’t have memories of my parents together, but obviously they were together, at that particular moment. There I was with my mum, being photographed by my dad. So that was like proof, even if I’m contradicting myself. But it’s all a constant contradiction, in a way. “

When her father was ill, this curious contradiction surrounding the role photography plays memory and perceptions of reality was driven home.

“Once he had this portrait of his sister and he started telling me, completely lucidly, ‘Hazel drowned recently, and her poor husband must be so upset.’ Of course she hadn’t drowned, but he’d made up this whole story about her life, how she died.”

“I didn’t disagree, because you can really upset someone with Alzheimer’s by contradicting them. So I just went along with it. But I was fascinated by how sure he was: it was like the photograph was giving him the certainty that the story he was constructing was true.”

West Cork photos

The Adrian Flowers archive covers a time period from the 1950s until the 1990s, an extraordinary cultural treasure trove spanning decades of immense societal and technological change.

Open one drawer of the filing cabinet and you find adverts for make-up, lager, cigarette ads in an era when these were glamorous and appealing. There’s food photography, fashion, stunning portraiture, and stranger things too: one envelope contains photos of a woman’s swollen, injured ankle, seemingly as evidence for some kind of court case.

There are endless opportunities for exhibitions on different themes. “I definitely want to do an exhibition of his early West Cork photographs because they are very beautiful,” Francesca says.

“Those are mostly 35mm slides. He was taking pictures all the time when he was here, but no-one ever got to see them: he’d have them processed, pick them up from the lab, bring the box back, and they’d never be seen again. There was never time.”

There’s no denying that the archive reflects an enormous legacy: although Adrian himself didn’t become a household name or “star” photographer, and preferred to refer to himself as a technician rather than as a creative, his studio was prolific and professionally sought after.

Some of his assistants went on to become very well known, not least Brian Duffy, who worked in fashion and is very well known for his Aladdin Sane photograph of David Bowie. Chris Killip, best known for his photographs of working class English communities, was another assistant.

“Dad had such broad interests and his personal work was very important to him as well,” Francesca says. “I’m in awe of how much work he did.”

“He called himself a technician and was not at all keen on being called an artist, which I really respect. I love his creative work but I don’t think it makes him an artist: it’s just as valid to say he’s a craftsperson and that’s what he would say. A craftsperson, a technician.”

Although he never officially retired, Adrian began withdrawing from his commercial work during the advent of digital photography.

“He didn’t like digital, for a variety of reasons,” Francesca says. “He was really good at doing everything in camera, and that was what people went to him for, because he was able to solve really complicated problems and set-ups. I don’t think he thought his brain could manage the transition: I don’t think he thought it would suit him.”

After his death, while his widow was selling the Lot-et-Garonne house, Francesca arranged for his archive to be moved, first to Kent, where she was based at the time, and into storage.

Now that she and her partner are renovating a house in Ballydehob, the archive has found a home of sorts, at least temporarily. She and Peter Murray have been resorting a former shop on the West Cork town’s main street for the past two years, and on the ground floor, there is space for the archive, even for small exhibitions.

Peter, with decades of curatorial experience in the arts world, has been assisting her with a website, The Adrian Flowers Archive, which started as a lockdown project where he writes on various themes and she collates the images.

“Thanks to Peter, we started the blog and he’s done about 40 posts now,” she says. “We didn’t know where to start but he’s done amazing research and very good writing, while I’d collate as many photos as I could. I’m so chuffed about that because it gives the project a value and meaning and structure.”

In the longer term, Francesca knows she will need assistance with her sometimes overwhelming task, and would consider donating it to an educational institute, somewhere with more resources than her own. The preservation and upkeep of the archive is by no means secure, and digitisation raises its own questions.

“The aim is to digitise it, but then do you get rid of the originals, the material?” she says. “That makes me really nervous. Where do you store all that digital material? Digital formats don’t last forever, either.”

A vase of flowers

On the filing cabinet behind Francesca there’s a vase: a metallic vessel, a classical shape like something from a still life. The story behind it belies Adrian Flowers’ representation of himself as a technician rather than an artist.

“This vase, to me, really represents him,” She says. “He designed it himself, and he’d have them made in different materials: a perspex one, a clay one, this one, which is resin with a metallic finish. It was the same design and he’d have it repeated.”

“If he was travelling, he would bring one with him and position it somewhere and photograph it, as though it were himself.”

To Francesca, this impulse is a precursor to today’s selfies and Instagram culture: a clever device, based on her father’s wordplay around his own name - his letterhead also featured a vase - but also quite a lot more.

“I find it quite moving and comforting, because wherever I’m living now, I have one of his vases,” she says. “It’s like he’s here.”

“Burn it”

Although Adrian rigorously, almost obsessively, documented his life’s work, it’s by no means clear that he saw it as forming a legacy beyond his own personal use.

“I always remember him saying, ‘there’s never enough time.’ I think he thought that once he got to France he’d have time to sort it out,” Francesca says. “I think he just thought it was…his.”

“I did ask him once, while he was still lucid. I said, ‘what are you going to do with all this?’ And he said, ‘just burn it.’ I don’t know how serious he was.”

With no will or official road map and just one possibly off-hand comment to go on, and conscious of what an enormous resource and social history the archive is, Francesca does not intend to burn the contents of the filing cabinets. Even when she feels she’s facing a Herculean task.

“The fact remains that he didn't say categorically what he wanted done,” she says. “It’s not as if he left a will that said, ‘this is what I want done with my effects.’ Equally, he left no means to support it, so it’s without resources. But I like to think that eventually, people will get a lot of pleasure out of seeing these.”

“There’s still so much to discover and I’m still seeing pictures I’ve never seen before. Can you image how distracted you can get, when you open one of these drawers? I just want to keep it alive, really.”

You can read more about the Adrian Flowers Archive on the official website, or on the Instagram account.

Really enjoyed this writing - a great bit of journalism, full of empathy and insight.