Make Corcaigh Irish Speaking. Arís.

Can the language we learned at school make a come back on the streets, parks, cafes, pubs and restaurants of Cork?

One day in March 2019, Emmett O’Shaughnessy decided to take his Irish to town.

And so he did, making his way to Gael-Taca on Sullivan’s Quay where upon entering the Irish language centre, which has a fairly pedestrian cafe, he started out by saying “Oscail an doras” (open the door). Closing the door behind him he said “Dún an doras” (close the door).

Over the next two minutes, as he proceeded to order a cupán tae and a coffee before moving on to quotidian subjects such as discussing the day’s weather, O’Shaughnessy probably spoke more Irish publicly than most adults in Cork do in an entire year.

O’Shaughnessy is not a native Irish speaker, he’s not even native Irish - he was born and grew up in Boston, but his mother is from West Cork, and he’s married to a Gaeilgeoir who is a teacher in a gaelscoil in Cork city.

He filmed his Irish language experiment for an ongoing series where O’Shaughnessy sets himself up to try a variety of new things: he’s grilled pears in a George Foreman grill, made a face mask from coffee, and shadowed the firefighters at Cork Airport for a day. So for Seachtain na Gaeilge in 2019, he set himself an Irish language challenge, a language which he is slowly learning, and which is rarely ever heard spoken publicly at length in Cork.

Realistically, you’re more likely to hear Chinese, Polish, French, Spanish, Russian, Urdu, Arabic, indeed any of the languages that make up this multicultural city, than Irish, on the streets or in the shops of Cork. Ask yourself, when was the last time you heard a conversation in Irish outside of a classroom setting in Cork? Similarly, if you wanted to use Irish in Cork, where could you go and what would the reception be?

The thing is though, there are venues and avenues, online and in real life, and passionate speakers - revivalists - who are making a space for the language to remerge in Cork, and while it’s not easy, especially in the midst of a pandemic, they’re committed to the long road to make Corcaigh Irish speaking arís. Or at least pockets of Cork.

Constitutionally speaking, we’re all native speakers. Except…

When we say “Irish is my native language” what we are referring to, as Aidan Doyle a professor of new Irish at University College Cork, points out to me on a sunny but windy afternoon outside the O’Rahilly Building in UCC, is the constitution.

That’s because Article 8 - the article that some love to hate -states:

The Irish language as the national language is the first official language.

The English language is recognised as a second official language.

There’s probably not many countries where the second language is by a country mile and some the most widely spoken language, and the first official language is for the most part absent from and in most conversations. But, that is the state of the Irish language in Ireland in 2021.

Article 8 upsets some people no end, to the point where they will find road signs written in Irish, and go to great lengths describing how such signs are road hazards. This article is probably not for them. However, Article 8 helps inform why we all learn Irish in school, for up to 14 years of our life. Simply put, it’s our native language.

Professor Doyle, author of “A History of the Irish Language”, sees no reason why we couldn’t rewrite the constitution, provided there was enough support for a referendum. He’s also pragmatic enough to allow that this might never happen either, as there are probably more pressing concerns, and it’s unlikely many politicians will die on the proverbial hill on this issue.

With his students, professor Doyle tries to avoid the term native entirely, preferring instead to use the linguistic terms L1 and L2 - L standing for language.

“L1 is the language you grew up speaking, what you spoke at home, what you heard in the community. And then L2 is anything else after that.”

But, as professor Doyle is quick to point out, “Irish is not taught in this country as a second language, there’s kind of an assumption that everybody’s a native speaker, a first language speaker of Irish, and then the education system is built around that which I think creates a lot of problems.”

One of those problems is that there is a much higher expectation of Irish language learners in comparison with a learner studying French says professor Doyle. But then again we don’t study French from the age of 5 all the way through to 18. And so we’re back to square one. Why study it? Because the constitution says so?

One reason we study it is because we have to, but also because we think Irish is important. As professor Doyle points out, surveys on attitudes towards Irish consistently reveal that the language is of great import to us.

“Every year people there’s a census on people’s attitudes towards Irish, it’s a firm favourite, and everyone says it’s really important,” says professor Doyle.

But as professor Doyle asks, how do we interpret that word important?

“Does that mean it’s really important that somebody should be speaking it but not me?”

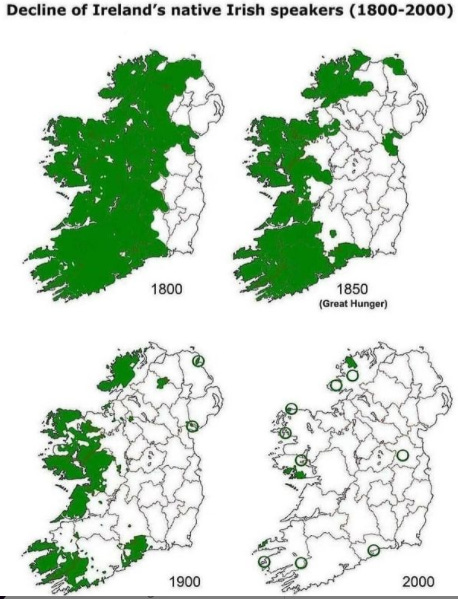

The thing is though, we do have a considerable chunk of of people speaking Irish: according to the 2011 Census, 1.77 million people (41% of the population) defined themselves as Irish speakers and 77,185 people said they spoke Irish on a daily basis outside the education system. There’s no shortage of Irish on TV, on the radio and online. Clearly the State provides and Irish exists, although it has undergone considerable linguistic changes as the population of L1 speakers shrinks. Professor Doyle thinks Irish will continue to exist in these cultural and professional spheres. The question is though can it break through and on to the streets and parks?

Love for the sráid

John Ó Ríordáin is not short of ideas in general, and specifically when it comes to the revival of speaking Irish in Cork. But as well as ideas, he’s a man of action.

He produces Pod Beag, a pithy and helpful podcast with bitesize nuggets of Irish-language lessons narrated in Irish and English, and he also set up Sos Lóin, a lunchtime gathering for anyone who wants to speak Irish, which has moved online since the pandemic put paid to meeting in person.

Originally from Millstreet and now living in the city with a young family, Ó Ríordáin told me that coming from a small town he’s well used to getting up off his arse and organising events.

“My mother was always organising bake sales for this, that and the other in the town,” he says.

One of Ó Ríordáin’s ultimate goals is to have an Irish-speaking street in Cork city; his commitment to this street is so resolute that he’s incorporated the word sráid (street) in his email address.

Ó Ríordáin has a very direct and specific route to getting people in Cork speaking Irish again, and it boils down to one word: craic.

“When you say Irish to people, it means two different things. It’s either the subject in school which everybody hated, myself included, or the language which is just talking to people and having a bit of craic.”

Ó Ríordáin thinks that most people are quite happy and proud of the language part but hate the education part. It follows then in Ó Ríordáin’s theory that they get turned off Irish the language, because they hated Irish the subject.

The first thing that needs to be done is to separate that out, to say “look it’s not education it’s just a bit of craic.” (Professor Doyle told me you can’t really separate the two - to enjoy the activities of a language, you need to learn the language i.e. through education).

Given that craic has such a central place in so much of what goes on in Ireland, Ó Ríordáin thinks that there should be an Irish-language aspect to go along with anything that has a social or playful element to it. By example, he says that the Christmas market on Grand Parade should have a “little section for people who speak Irish so they could go and chat away.”

Ó Ríordáin contends that if people start seeing and hearing Irish outside of the classroom “in places that are great fun” it will spur people on to use Irish more. In this sense, it’s an argument that activists across a wide spectrum use to advance their causes. Just as the cycle lobby contend that the more cyclists that are on the road, the more likely other people are to incorporate cycling into their daily routine, Gaeilgeoirs like Ó Ríordáin, believe that a language that is heard in the routine places we inhabit, then that can only be a good thing for its future health and well being.

Ó Ríordáin’s big idea, as he calls it, would be to turn the length of Cook Street, between St Patrick's Street and Oliver Plunkett Street into a mini-Gaeltacht.

“Take that whole street and say ‘look, any businesses that are going in there now you need to have someone who can speak Irish’”.

Ó Ríordáin’s inner-city Gaeltacht, the sráid, would have pubs, cafes and restaurants and it would be a place open to all, where Irish would be the first language. While Ó Ríordáin recognises this sráid is a fantasy project, he contends there is a significant silent minority out there who have gone to gaelscoileanna, but have nowhere to speak the language.

“It’s amazing how many people speak Irish. The people are there, they’re just kind of hidden.”

“You can have all the gaelscoils in the world, but if you have nowhere to speak it then the language dies.”

If you subscribe to the “build it and they will come” philosophy then Ó Ríordáin’s mini-

Gaeltacht on Cook Street might work, if the cafes and shops were just as good or better than what’s available on other streets. Likewise, even if everything is conducted in Irish, that’s hardly likely to turn punters away, especially if you consider that in regular years half of Cork flocks to non-English speaking countries to spend their money.

Claire Nash, the proprietor of Nash 19 on Pembroke Street, has hosted Irish language and Irish cooking events during Seachtain na Gaeilge, and she told Tripe+Drisheen she would “absolutely love” to do more of these. Likewise, bar owner Benny McCabe said he would be glad to help out in this space also.

“All I did was show up”

There is sometimes a misconception in Ireland that people who speak Irish went to all-Irish schools, or grew up in Irish-speaking families, or had an edge somehow. Ó Ríordáin, who now enjoys speaking Irish everywhere and anywhere, left school hating the language. He’s not from an Irish-speaking background; he got a D in pass Irish in the Leaving Cert.

“I had very little Irish. I hated it. I forgot everything.” In other words, Ó Ríordáin is a stand-in for many of us who have come through the education system in Ireland.

His route back to the Irish language started in earnest about four years ago, prior to the birth of his daughter.

With his change of heart he went back to study at night on his own time and his own dime. One of the classes he joined was geared towards adults and parents who had never studied Irish before, such as immigrants living in Cork whose kids were now learning Irish. Hearing and seeing completely new learners gave him the confidence to keep going.

Not all the classes he attended were great according to Ó Ríordáin, and he chaffed at one former primary school teacher who insisted the class full of adults had to raise their hand anytime they had a question.

The process of learning Irish again forced Ó Ríordáin to reflect on why he was learning the language; why was he really doing it? The answer turned out to be fairly simple: he wanted to speak Irish with his daughter. “So I decided the best way for me to learn is probably just to speak it,” he says.

So with this wisdom, Ó Ríordáin went from the classroom setting to conversation circles, which he found to be more suited to the way he wanted to learn and speak the language, in a less artificial surrounding.

This setting became the basis for setting up Sos Lóin, an informal gathering for anyone who wanted to turn up and speak Irish during lunchtime. As Ó Ríordáin points out, incorporating an Irish conversation activity into the working day is more amenable for anyone who has duties to carry out at home after work.

“I fired it up (Sos Lóin) on Instagram and Twitter to see who’d come along, and a few people came along and just chatted away.”

“That’s literally all I did: put up a post on social media asking if anyone wants to speak Irish with me at lunchtime on Tuesday and a few people turned up.”

The media also took notice; Newstalk, Radio na Gaetachta and local media outlets were quick to interview Ó Ríordáin about his initiative.

“There’s so few outlets for people to speak Irish in a social, non-education way, that my little thing is on national radio. It’s sad actually in one way.”

Originally, Ó Ríordáin and the lunchtime crew used to convene at Gael-Taca but one day while they were locked out on the street waiting for the premise to open up, the owner of O’Sho on Barrack Street sauntered by, and, Cork being Cork, knew one of the participants who explained what was going on, which resulted in an invite up to O’Sho to carry the conversation on.

O’Sho then became the base for Sos Lóin, and the bar even went on to win an award from Gael-Taca for hosting the event.

If anything, Ó Ríordáin, finds the attention, awards and compliments a bit head scratching. As he says, “all I did was show up and ask a few people if they wanted to speak Irish.”

For Irish to be heard on our streets, Ó Ríordáin believes there needs to be a groundswell of individuals doing bits here and there. Individuals such as Cillian Brennan.

ReRá agus Óró

Beginning in 2012 and running all the way to 2019, Brennan ran ReRá a monthly cultural night in the city centre that centered around storytelling and the Irish language. Brennan took the inspiration from a storytelling competition he attended down in Listowel a few years back.

There was a lot else folded a lot into the night: quizzes, storytelling, poetry, stand-up comedy and live music (including appearances from John Spillane) and the evening always unfolded in Irish. Besides ReRá, Brennan also founded and runs Óró, an Irish-Language choir which rehearses and performs exclusively in Irish. The choir rehearses at Gael-Taca - although it’s on a pandemic pause at the moment - and Brennan tries to keep the ship of singers afloat, as numbers go up and down.

As he says the choir is as much a social gathering as it is a musical endeavour.

Brennan’s a hustler and “chief bottle washer” for the Irish language and he knows both the efforts and the rewards that go into creating a space for the language outside the classroom in Cork.

Talking to people who speak Irish on a regular or semi-regular basis, there’s a common thread that often emerges and that gives credence to the “silent minority” theory of Irish speakers.

Brennan remembers nights after finishing up ReRá at the Mardyke cricket grounds and rolling up to The Crane Lane in the city centre, a gang of 20 or so sitting in the bar speaking as Gaeilge, and inevitably the language would attract others in. “I don’t know how many times we’d meet people who were in Gaelcholáiste or gaelscoil who hadn’t spoken Irish in 10 years or since they left school.”

As Brennan explains, that was the drive behind ReRá. “People don’t have the opportunity to speak Irish.”

There’s a kind of a tragic aspect to this; the image of a language, our language, that resides inside so many of us, laying dormant and slowly wilting for the want of company and expression.

With both the choir and the culture nights, Brennan is well placed to answer one of the questions that formed the bones of this piece: how do you get Cork to become an Irish language speaking city?

“The short answer is you probably won’t,” Brennan says. Part of the problem which he identifies is keeping institutions going, maintaining new blood and keeping members coming back so that an event such as ReRá can continue even when he has “to take his foot off the pedal.”

If Brennan sounds downbeat on the possibilities of more widespread usage of Irish in Cork, he’s also a romantic, and he has hopes and dreams for how and where he’d like to see the language used.

While Ó Ríordáin dreams of his mini-Gaeltacht on Cook Street, Brennan has set his stall on an Irish-language GAA club in Cork.

There’s precedence for this, as Brennan points out: Dublin has Na Gaeil Óga founded in 2011, and Galway has Gaeil na Gaillimhe started in 2016. Neither of these clubs take a tokenistic approach to Irish: “It’s 100 per cent through Irish,” Brennan says.

“They started off a club with basically a senior men’s team,” Brennan says of Na Gaeil Óga, “and now they have two football teams, a hurling team, a camogie team, a ladies football team and 400 people playing underage.”

While people might wonder how such a club would work here in Cork, the answer lies in the model used in Dublin, and then Galway. Starting with a senior team, and then working down, setting out schedules for trainers, and “bringing in parents and giving them coaching courses so they could take it on.”

As Brennan points out, there are families where Irish is used at home, either frequently or all the time. He speaks to his two “smallies” all in Irish. And considering that Cork has 30 gaelscoils and at least four Irish-language secondary schools, there “would be a playing populace there.”

Brennan sees no reason (and every reason) as to why an Irish-language GAA club could not set up in Cork. As he told me, on an individual level GAA people, including passionate Gaeilgors, are all ears and supportive, but then in the next breath they’ll explain how they could never walk away from their own club.

“There’s a weird thing in Cork though I think,” Brennan says. “A lot of the (Irish language) organisations are there and do do a lot of good work, but kind of working independently, ploughing their own furrow and they don’t reach out to each other.”

This is a criticism that I heard quite often in researching this piece, and equally politics is never far behind anything in Ireland.

I asked Brennan if something as crude as wearing a badge showing that you speak or are learning Irish would help with the revival of the language in Cork. There is something analogous on social media where people often (and proudly) declare their Irish language ability, whether they are learners or fluent speakers. Would people be more likely to use Irish if the person behind the bar or on the till at SuperValu, or even in the park bench nearby was wearing a “Tá Gaeilge agam” badge? Would this be a start, as artificial as it sounds, to engendering conversation?

But, as Brennan pointed such an artifact does exist, albeit in a more subtle and stylish form, with the fáinne, a pin that signifies the wearer is willing and able to speak Irish. According to Brennan the fáinne is worn “a good bit in Dublin”. You’re also more likely to hear Irish, and a better standard of Irish in the capital, Brennan says.

If Irish is going to break from beyond the classroom, it’s going to require more of us to speak it, and more of us to go back and learn it. And then to go out and use it, whether at a sports club, a cafe or a choir.

And something we’ll have to face up to is that learning a language takes time and effort. As professor Doyle wrote in an Irish Times op-ed from 2014, we are not born with an Irish language gene:

There is a widespread belief that Irish is somehow encoded in our DNA, and all that is needed is to discover this language gene, and we’ll all start speaking Irish as competently as we speak English.

After leaving my interview with professor Doyle I was driving home past the Lough when an American-accented DJ on the radio paused her mid-evening show for a nuacht bulletin. We have all heard these short Irish-language news bulletins hundreds of times, but on this occasion I tuned in to see how much I could parse together. The short answer is not a lot. Like many (many) others I want to be better at Irish, and I want to speak it. I hear my eldest son use the new words and phrases he picks up at school, around the house, and he does so without any inhibitions in the way kids do. He’s only been learning Irish since we moved back to Ireland, and I’d love one day to be able to sit down and have a conversation with him as Gaeilge, like his mother does when they talk together in Japanese.

There’s something about the language, perhaps because Irish us our language it’s a link to our past, and also like any language it’s a way of connecting to others, to a network, and to another world, which is what happens when you learn another language and discover all the unquantifiable space and culture a language exists in.

And so to finish, I’ll leave you with the words of someone I grew up with, far smarter than me, and who mastered Irish through a fair amount of long nights in the company of old books, and likely too his mother’s prayers. In a piece he wrote for Brainstorm on the RTE website in 2020, Ken Ó Donnchú (my youngest brother, a colleague of professor Doyle’s at UCC), sounded a note of caution to Irish language learners, before offering encouragement.

“Relearning a language is a lesson in humility: you immediately surrender the ability to say whatever you want, whenever you want.

“Those who wish to re-engage with Irish, or any other language, in the new lockdown should not lose faith. Accept that your linguistic freedoms, as your physical movements, will be restricted for a time. Language learning can be slow and tedious, and progress may seem minimal. But the slog earns a great reward. Whether it be understanding a line of a song or a poem in its original, or having a basic conversation in the target tongue, the feeling of achievement is ample reward for the effort.”

Very interesting article with some excellant ideas. It helps to distinguish between the effects of 'school Irish' and conversational Irish and It motivates me to go back and take a fresh look at ways to speak Irish in Cork ( city and county) Sean O Riain, Carrigtuathail