Locavore: a month of eating only Irish food

A globalised food supply chain is causing irreparable environmental harms; a month of eating only Irish produce has shown me how.

It’s apple season.

All around us, the bounty drops to the ground and is left, by many, to rot.

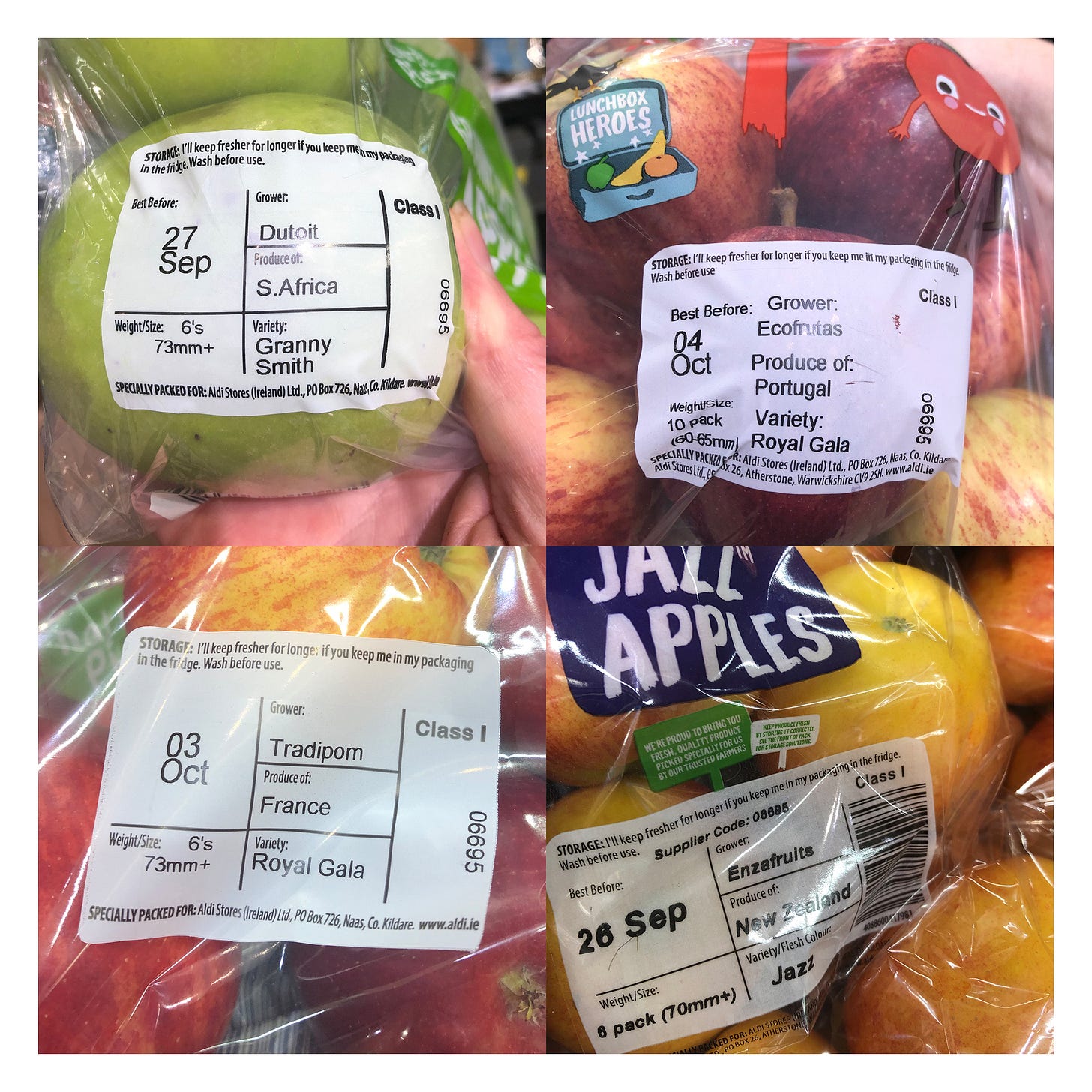

Meanwhile, in the supermarkets, there’s not an Irish apple to be found. In my local Aldi, the food miles on the plastic-wrapped apples are breathtaking: New Zealand, South Africa, Chile, Portugal, France. Only the cookers are Irish.

The same is true in the vast majority of supermarkets.

If it seems a trifle deranged that I’ve been standing in supermarkets muttering to myself and photographing the fruit, be forgiving: this year, for the second time, I’ve attempted something which seems like it should be simple, but in reality is scarily difficult.

I’ve spent the month of September eating only foods produced and grown on the island of Ireland.

Last year I did it too: inspired by Kerry farmer and artist Lisa Fingleton, who I had interviewed for my Irish food sustainability podcast, I took on her 30-day Local Food Challenge.

This does not mean eating things labelled as Irish, because after all, this is no guarantee of provenance: freshly squeezed orange juice can pick up a Blas na hÉireann award. There’s sushi labelled as Irish. More Irish chocolate than you can shake a diabetes test stick at.

That’s because there’s a law that permits you to label a food as Irish, or even as “Made in Cork,” as long as it has gone through a “substantially transformative process” here.

The problem with all of this labelling of imports is that it is currently giving us a misleading idea of where we stand with actual food security.

Go into a Dunnes or an Aldi or a Supervalu and the bulk of the processed foods that you will find labelled as Irish will only be partially made with ingredients grown here, at best.

It’s not a bizarre paranoia to have concerns about food security. Our closest neighbours are currently experiencing empty shelves, largely related to the political ramifications of having left the EU, and they are inadvertently shedding a light on the uneasy fact that a globalised food production and distribution system concentrated in the hands of a few giant retailers, reliant on cheap migrant labour and the petrochemical industry, is always just a few links in the chain away from collapse.

1% of Irish agricultural land is horticulture

I don’t take on the 30-day Local Food Challenge because I believe that everyone should be immediately switching to an all-Irish diet, despite the environmental and nutritional benefits it would bring.

Eating only Irish can be expensive and difficult, and the way things currently stand, despite some supposedly impressive metrics around Irish food security, once you look outside of tonnage, it’s clear that we are not growing the necessary diversity of produce to feed our population, unless we were all to get scurvy by subsisting entirely on our overinflated, export-driven meat and dairy sectors.

Lisa once told me that only 1% of Ireland’s 4.9 million hectares of farmland is horticulture.

This seems insane, but according to CSO figures from 2016 it may even be an overestimation; just 71,000 hectares, or 1.44%, is devoted to “other crops, fruit and horticulture.” But this includes biofuel crops like oilseed rape, as well as fodder crops like maize.

And these figures were compiled just one year after the abolition of milk quotas, and the attendant and continuing focus on intensifying Irish dairy ever since.

So if anything, Lisa’s 1% figure may be an overestimation.

An absolute mania for living experiments

I do the 30-day Local Food Challenge because I’m a firm believer in learning through doing and I have an absolute mania for living experiments as a result.

From interviewing naturists nude in a jacuzzi to sitting a Mensa test, from living without buying any single-use plastics for a month, to eating out-of-date food for a month, to signing up to ride for Deliveroo, I’ve taken on a lot of strange things in the name of learning.

So far, the 30-day Local Food Challenge is the one that has brought about the most profound change in my life.

In the past year, I have worked on an Irish Food Sustainability Podcast exploring the questions raised by my locavore experiment: why was Ireland’s indigenous sugar industry dismantled? Can you run a Michelin-starred restaurant without olive oil, lemons or pepper? And why does Ireland import 260,000 tonnes of wheat each year while feeding the bulk of our homegrown grain to livestock?

Inspired by the drive to grow more of the food we eat, I worked on raised beds for our veg garden and even installed a polytunnel in a bid to extend our growing season and diversify what we can grow.

This year’s challenge

Because of the tunnel, I was eagerly anticipating this second year of the local food challenge. I had chillis, and an almost foolhardy quantity of tomatoes, edamame beans, peppers.

Pride comes before a fall, they say.

I got blight.

Weeks out from the challenge, my tunnel tomatoes withered and died on the vine. I still had eight plants in my mum’s small greenhouse, but the bulk of my beautiful varieties pulled a full-on Black ‘47 on me. A valuable lesson in the cruel uncertainty of growing veg, in the vagaries of my own slap-dash horticultural technique.

September got off to an even more rocky start when I tried to order a sack of Oak Forest Mills’ peerless white spelt flour only to discover they couldn’t supply it.

It’s amazing how much Italian food is possible on the locavore diet if only you have flour: pizza, foccacia, fresh pasta all compliment the garden veggies brilliantly, and a caprese salad only requires substituting rapeseed oil for olive oil.

In the first week, I still had a couple of kilos of this fantastic stoneground flour left, so I could rustle up some Irish pizza.

But by week two, potato fatigue was setting in.

Potato fatigue and digging for your dinner

Eating only Irish foods is incredibly expensive and, as with last year, there were times when I just couldn’t fork out the necessary sums, or didn’t have the time to traipse around the various shops where I know local produce can be sourced. So I wanted to get by on as much of our own garden produce as possible.

Which was heaps. Lettuce, mizuna, kale, courgettes, peppers, carrots, onions, the surviving tomatoes, herbs, parsnips: this year, the extra work really paid off and there were days where most of what I ate came from the garden.

I had a great potato bed too: it, too, had gotten blight but I had spotted it early and taken away all the leaves, leaving a fantastic crop of a second early variety safe in the ground to dig as I needed.

Digging potatoes is one of the most satisfying things in the world, each glorious tuber a hidden white-gold treasure to be unearthed.

But even my potato passion wore thin. Without the convenience of pre-made bread or scones on the menu, I would wake hungry, sigh and start frying spuds. Oats, of course, are about the only other native carb available for human consumption, and there are loads of breakfast options there, even if porridge isn’t your thing: toasted oats or homemade granola with yoghurt, honey and berries is eminently doable.

Big, hearty dinners are easy to rustle up, and plenty of garden veg went into soups and salads at lunchtime. As I knew from the year before, I definitely wasn’t going to starve.

The year’s increase in veg gardening led to more preserving: a glut of cucumbers became cucumber pickle, I bottled jars of homemade tomato sauce and then, because I had chillis and tomatoes to spare, I branched out into experimenting with making homemade hot sauce and ketchup, which were both surprisingly authentic.

“I grew this ketchup!”

I was so excited by the ketchup that I labelled it “I grew this ketchup.”

Apple cider vinegar was a key ingredient in these things and we’re lucky to have a lot of it doing the rounds. I even found an apple balsamic vinegar from Llewellyn’s orchard in Lusk: I interviewed David for my podcast last year and, speaking of imported apples, he shed substantial light on the reasons why many retailers aren’t stocking Irish apples.

A lot are to do with the EU’s ludicrous standards, which list the exact permitted dimensions of apples of different varieties, and include what percentage of the skin surface is allowed to be blemished. These exacting standards are simply unmeetable by the bulk of Irish growers, and the profit margins are too slim.

The animal connection

Of course, Irish dairy is abundant and of phenomenal quality. Gloun Cross milk from Dunmanway comes in glass and is fantastic; if you order it on Neighbourfood you can return the bottles for 50c, bringing the price per litre down to €2.00. Amazing cheese is everywhere, yoghurt too.

Meat and eggs are also easy to come by.

Vegetarian and locavore is eminently possible if you have eggs and cheese in your diet, but I don’t fancy a vegan’s chances on the challenge: Ireland produces no protein crops to speak of. I was vegan for several years, but no longer, and I harbour unfashionably nuanced opinions about the alleged benefits of a plant-based diet for the planet: I think that not all vegan food is good for the planet, and that not all meat and dairy have to be bad for the planet.

I think that intensive, chemical dependent animal rearing for export is a nightmare for Irish soil, water quality and biodiversity. But I don’t think that’s the only picture.

When I asked Sligo organic grass-fed beef man Clive Bright what he makes of veganism, he told me, “I don’t know how you can have an organic system that’s truly sustainable without some animals.” Animals put nutrients back into the land; certainly, you can sow green manure crops, but the delicate balance between grasslands and grazers is not easy to replicate.

So no, I don’t believe that a Tesco vegan burger made with 18 processed ingredients including palm oil from all corners of the earth, shipped to a plant for further processing, packaged excessively and then shipped out to the retail giant’s supply chain can possibly be better for the planet than Ballea lamb raised near Carrigaline, slaughtered on the Northside 30km away and delivered to O’Mahony’s craft butchers in the English Market.

Cheap as chips

Thankfully, in recent years, Irish rapeseed oil has become relatively common. It’s costly (At its cheapest, in Aldi, it’s €2.99 for 500ml) and it has a distinctive flavour that can take getting used to: it’s great for roasting, fantastic in dressings but I tried making mayonnaise and it was absolutely revolting, nowhere near neutral enough in taste.

This year, I became keenly aware that animal fats were the answer for our ancestors. But I’ve only ever heard horror stories from my dad about the thick layer of grease left on the roof of your mouth by dripping.

An absolute mania for living experiments, I’m telling you.

As it happens, chips double fried in dripping are absolutely incredible, served with Atlantic sea salt from Beara, Ballyhoura Apple Cider Vinegar and the ketchup that I made.

Who would have thought it? Chips make sense. I had them four times during the month and my arteries remain miraculously unclogged. I can’t pretend I’m going to keep this one up though.

What did I miss? Coffee and wine, both of which are bad for me. My partner makes cider, so we drank some cider.

Fatty excesses aside, the 30-day Local Food Challenge is actually incredibly healthy.

The fact that Ireland has no sugar production at all (listen to my podcast episode about the demolition of the sugar industry and you’ll be left scratching your head) means that sweet things are pretty much out of the question apart from honey and fruit.

This doesn’t matter to me: I’m the kind of person that chooses starter and a main over a main course and dessert any day.

But I did get one hankering last week, and whipped up an all-Irish berry cheesecake with a pinhead oatmeal biscuit base.

I had to make my own cream cheese for this, which I did with full-fat milk and a little cider vinegar as an acidic element. All the ingredients were just the very best Irish produce going: eggs from my mum’s hens, Bandon butter, honey from a lady 10km away, Wexford strawberries and raspberries, blackberries from our laneway, Macroom oatmeal, and Glenisk organic cream and creme fraiche. (Here’s wishing Glenisk all the best after their devastating fire this week.)

It was the most delicious dessert.

The end of the month

Tonight is the end of the 30-day Local Food Challenge. I do have designs on a blow-out Indian take-away over the weekend at some stage, but after that, I am going to try to continue most of my affordable locavore habits.

It’s kind of hard to stop once you start, because you check labels automatically.

Will I reintroduce a couple of luxuries like tea, coffee, lemons and olive oil? Yes. And I’ll be buying a lot of sugar, because preserving season is here.

But I don’t want to go back. There’s nothing good about the imported exotic fruit that supermarkets let us believe we can eat year-round on 49c special offers: it’s only harming the planet and its life-forms, not least other humans, who can’t possibly be making anything approaching a living for those prices.

There are many other conversations that need to happen that are for another day: conversations about why good quality local foods are the preserve of the few, while most people are forced towards the most mass-produced and least sustainable options.

Because outside of this personal journey, I’d like to see the movement grow.

I’d like to see chefs, food columnists and magazine recipe writers, restaurant reviewers, home economics teachers, hoteliers and everyone else who works in food to see their responsibility in this too: we need a constant conversation about provenance.

The 30-day Local Food Challenge might last for one month, but it also lasts your lifetime, because it creates a revolution in how you view your diet, and your place in the vast web of farming, growing, supply and sales, cooking and eating of which we are all a part.

As a living experiment, I recommend it.

If you want to be a part of the challenge next year, Lisa’s Local Food Project Facebook page is a good place to start: there is a growing community there of people all supporting each other to get involved.

Now where’s that Indian takeaway menu for tomorrow?!

Heard you with Ryan, brilliant and also read your great article. I too am so sick of asking in Dunnes for an Irish Apple!

As for the 49 cent avocados that never ripen.

We are finished with Avocado which need vast amounts of water to grow and have to come half way round the world to smash on our sourdough bread!!

Keep up the great writing !

Ps when are you doing an article about the massively talented and genuine Artist (from Bishopstown boy!) Conor Harrington??

Terrific article, thank you so much for your experiment, so insightful. We should all be trying this challenge.

Just one thought that came to mind, I’ve been reading a lot about nuts and their value as a protein, carbohydrate and mineral source. maybe consider adding a hazelnut cultivar to your garden or two?

On another note we (Green Spaces for Health, Cork Food Policy Council, Togher Tidy Towns + partners and Bishopstown Tidy Towns + partners) are trying to start two community food gardens, one in Bishopstown Murphy’s Farm and the second at Clashduv Park in Togher. They will be the first of their kind in Cork's public parks. The plan is to have eighteen raised beds in both, and a polytunnel, also an area of fruit and nut trees and fruit bushes. It’s very exciting and the gardens will be for the people living in those areas; young and old to come together to grow local food. Its early days yet but at the moment we are hoping to get the raised beds installed in Bishopstown by mid November and the same in Clashduv.