Light pollution: a problem for Cork city and county?

A city hotel uses "statement lighting" to impress, while environmental groups want stricter rules for countywide lighting.

After dark in the city

When new hotel The Dean opened on Horgan’s Quay in Cork city during 2020, the hotel’s design and black-cladded exterior made it instantly stand out.

But after dark, the hotel also stands out thanks to towering lights beamed high into the night sky.

The lights haven’t gone unnoticed by neighbours and those concerned with their potential environmental impact.

Tripe + Drisheen understands at least one Cork-based environmental group has been in contact with The Dean concerning its lights.

A “nuisance”

Thorsten Ohlow lives across the road from the new hotel, on St Patrick’s Terrace, with his young family. To him, the Dean’s lights are “a nuisance.”

“The spotlight in particular is a nuisance,” Thorsten says; sometimes, when he steps outside his house and looks up at the night sky, he mistakes the spotlight for the moon. Thorsten hasn’t complained to the hotel because he doesn’t feel the impact on his family is direct enough.

“It’s obviously not terrible, but I can see from an environmental point of view how it can confuse some of the nocturnal creatures because these are quite powerful,” he says. “They’re not just some dim lights.”

The terrace where Thorsten lives is a close-knit community and he says the lights became the subject of conversation after they were installed: “We were saying, ‘what’s that about?’”

It’s not only The Dean that he is concerned about: other new buildings on Penrose Dock and Horgan’s Quay all keep their lights on at night. With many more large-scale developments planned for the city centre in coming years, how much brighter are the city skies going to get?

Measuring light?

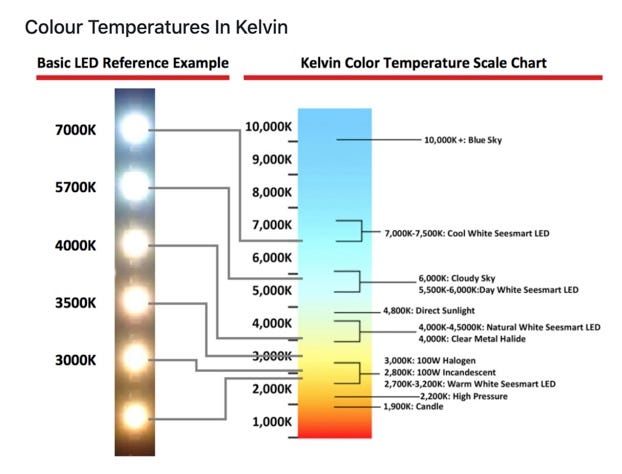

Public fixture lighting should be no more than 3,000 Kelvins, according to the International Dark-Sky Association. The Kelvin scale is a measure of the colour temperature of lights.

When we contacted them, The Dean hotel were unable to tell us the Kelvins of the lighting used on the hotel at night, which can be seen lighting up the night sky from as far away as St Luke’s Cross on the Northside.

To date, other than the environmental group the hotel has not received complaints about the lights, general manager Shane Fitzpatrick tells Tripe + Drisheen; he says he is willing to talk to anyone who has concerns.

“If anyone wants to come in and talk to me about it, there’s no issue whatsoever,” Shane says.

He acknowledges that conversations have taken place with an environmental group, but out of privacy for both sides, he can’t divulge further details, he tells JJ.

As to the purpose of the lights, he says they are part of the building design and they’re also not contravening any planning laws.

Public vs Private

For public lighting, Cork City Council says it operates in line with best practice guidance of a maximum of 3,000 Kelvins for street lighting, although this should be lower, 2,700 Kelvins, in conservation areas.

The Roads and Traffic Management department have an extensive published manual, which they furnished to Green Party councillor Oliver Moran when he asked for details of the lighting policy.

But a council press spokesperson confirmed to Tripe + Drisheen that City Hall is unable to investigate concerns about light pollution from private sources, as “unfortunately there’s currently no legislation in Ireland in relation to light pollution, as there is in the UK.”

Dark Skies Matter

Light pollution may not seem as pressing an issue as air or water pollution, but it is a problem that has been growing globally ever since the introduction of the first public lighting schemes in the 1880s, and it’s having far bigger impacts than you might think, including on human health.

For millions of years, humans evolved for periodic darkness; there is strong evidence that artificial light entering our eyes, even through our eyelids as we sleep, disrupts our circadian rhythms, our internal biological clock, by inhibiting our production of the sleep hormone melatonin.

This may be a good bit more serious than just not getting your full eight hours.

Melatonin suppression is even linked to cancers including breast and prostate cancers.

And if Artifical Light At Night, or ALAN, as it’s endearingly abbreviated, is wreaking havoc with human biorhythms, it’s doing the same for a vast array of creatures, from bird life to nocturnal species like bats, moths and hedgehogs, all of which are found in Cork city.

Major population declines in species of moths and bats has also been linked to light pollution; one-third of flying insects attracted to artificial lights die.

Ireland: the darkest skies in Europe, but for how long?

While Ireland has some of the darkest skies in Europe, light levels here have increased dramatically over the past few decades. Between 1992 and 2010 light levels shot up by 60%. Nearly half of Ireland’s population, 45%, now can’t see the Milky Way, according to research by Dr Brian Espey of Trinity College Dublin.

Nationally, Dark Sky Ireland is at the forefront of highlighting the adverse effects of light pollution on both animals and humans.

Cork Sky Friendly Campaign (CSFC) launched in 2017 and has been working in tandem with environmental groups and public bodies including Cork County Council to drive change, especially around the area of retrofitting public street lighting.

They want to preserve what remains of Cork county’s dark skies.

Cork Sky Friendly Campaign member Clair McSweeney, who managed the Blackrock Castle Observatory for 13 years, tells Tripe + Drisheen that light pollution affects night-time pollinators, moths and a variety of insects, “but also astronomers, who are night-time creatures as well.”

Clair says the work CSFC does is about “brining people around” to understanding why dark skies matter, citing the recent tie-in between The River Lee Hotel and Blackrock Castle Observatory: the city centre hotel consulted with the observatory for its pop-up installation at To The Moon at The River Club, and donated €1 from each cocktail sold to Dark Sky Ireland.

When it comes to other hotels like The Dean, “They’re new in town,” Clair says. “They have to show a bit of respect.”

A €53 million LED upgrade: more light, or light well-managed?

Cork Sky Friendly Campaign have responded with caution to January’s news that Cork County Council is heading up a €53 million LED upgrade scheme in the south of Ireland, the so-called Public Lighting Energy Efficiency Project (PLEEP), South West region: Cork, Clare, Kerry, Limerick and Waterford.

This massive project aims for energy efficiency, replacing current lights with 77,163 new Light Emitting Diode (LED) luminaries across 5 Local Authorities and 24 Municipal Districts.

It’s part of a national €150 million scheme to upgrade 220,000 lights, which, Cork County Council’s press office says, will reduce CO2 emissions by 5,000 tonnes annually and save local authorities €5 million in energy and maintenance costs each year.

But while the project objective is to maximise energy savings and increase energy efficiency, what will it do to light pollution in Cork county?

Cork Sky Friendly Campaign say they are disappointed that Kelvin guidelines for the project seem to have been left at the discretion of project contractors: they feel there was an opportunity to impose stringent criteria, especially in areas of environmental sensitivity.

“Light pollution is one of a number of elements that will be considered in the overall design of the luminaire and as such must be considered in the context of the visual environment and public safety with respect to each particular lighting location,” a Cork County Council press spokesperson tells Tripe + Drisheen in an emailed statement.

However, “the contractor will be responsible for designing the luminaire in accordance with the contract specification,” and while lighting in environmentally sensitive areas is recommended to be 2,700K, “it shall be considered on a scheme-by-scheme basis.”

This is an opportunity lost to provide a comprehensive cap to light pollution, according to Cork Sky Friendly Campaign.

“Our main feedback is that the wording seems to allow quite a degree of flexibility and CSFC would be concerned that this could be interpreted to allow more of the higher 4000K,” a CFSC spokesperson says in an email.

“There needs to be stronger adherence to the 3000k and in fact a bit more consultation with the public on areas they wish to have greater sensitivity of lighting 2700k or no lighting e.g. for bat corridors etc.”

Seeing the Milky Way in Allihies

Astronomer Denis Walsh moved from Cork city to Allihies, the picturesque former copper-mining village at the tip of the Beara Peninsula, about 15 years ago. Denis is a scientist who works in science and astronomy outreach with the Allihies Coastal Education Hub. Before moving west, he taught basic astronomy with MTU Blackrock Castle Observatory for twelve years.

He’s also a member of Cork Sky Friendly Campaign.

He says he was “unhappy with the lack of clarity” around how the individual contractors would be working in each area.

Allihies has not begun its lighting upgrade yet, but Denis hopes that the dark skies in the area, some of the darkest in Europe, will be recognised and preserved in the upcoming lighting upgrade.

“They haven’t replaced the lighting fixtures here in the village yet, so it all seems a bit far away at the moment, but we want to get a handle on approaching the council to talk to them about implementing guidelines,” he tells Tripe + Drisheen.

Energy efficiency: electricians left in the dark?

Getting the message across to the public that light pollution is every bit as much a problem as air or water pollution can be difficult, but, Denis says, a mounting energy costs crisis means that energy efficiency is to the fore in people’s minds.

“People are becoming more aware of the waste of energy as the price of electricity is going up,” he says. “They become aware of leaving the lights on and how it affects their own bill, and then if they see streets with a lot of lights on and no-one around, it’s kind of logical to start seeing wastage. They’d think of that before they’d think of any light pollution impact, I think.”

But public lighting, as important as it is, is only half the problem in the county as well as the city, Denis points out. Businesses, farms and private homes are entirely unregulated as to their choice of lighting.

“A lot of people are installing outside lights because they’re cheap and the electricians installing them don’t have any guidelines: they just get the cheapest, brightest ones,” he says. “You have farmers installing street lamps in their yards, and that’s all very well for workplace safety, but there needs to be better guidelines to make the approach a bit more uniform.”

“I feel that electricians are in the dark about the need to install lights that are of a warmer colour to lessen the impact on wildlife.”

Denis has the use of a light meter, the property of Cork Astronomy Club; it doesn’t measure Kelvins but something called the Bortle Scale.

“Kelvin relates to the colour of the lamps, but the Bortle Scale is general light pollution,” he explains. “The simplest scale is called a Bortle Scale, which has nine levels, with nine being the most light pollution and one being totally dark.”

How does Allihies rate?

“It’s two, all around here. Same as the Kerry Dark Sky Reserve. It drops to a one on the Western end of Dursey.” This is about as good as it gets.

“But the big measure is if you’re able to see the Milky Way. The Milky Way can be seen strongest in summer and autumn, but you can still see it any time of the year if there are clear conditions and the sky is dark enough. That’s the real test of a proper dark sky.”

In Allihies, on clear nights, Denis takes astounding photographs of the Milky Way and other celestial bodies.

A Dark Sky Reserve for West Cork?

Ireland has two so-called International Dark Sky Reserves: such is the extent of global light pollution now that truly dark areas are a treasured commodity.

Kerry International Dark Sky Reserve is near Derrynane and Mayo International Dark Sky Park is in Ballycroy and Nephin.

Denis believes that the Beara peninsula is eligible for a dark sky reserve of its own; it is, after all, about the same on the Bortle Scale as the Kerry International Dark Sky Reserve.

It would be a boon, he says, for local tourism as well as for awareness of light pollution and its place in the scheme of things, the importance of preserving what remains of our dark night skies not only for biodiversity and animal populations, but for humans too.

“The sky quality is exceptional here,'“ he says. “I have an idea of conserving this aspect with official recognition from local government, hopefully culminating in a designation from the International Dark-Sky Association. I joined the CEF for this and a number of other reasons, including the recognition of the link between bat and insect populations and pristine habitats.”

“It would bring an awareness to people, and it would be a source of revenue for astro-tourism; people will travel to take a photograph. But above any of that, there is an obvious benefit to having a natural rhythm of light and dark. Light pollution can upset insect and bat populations, but it can affect people’s mood as well. There’s a community of welfare approach that can be taken here.”