Good riddance to Strategic Housing Developments?

The controversial SHD system for fast-tracking large housing developments is coming to a close, but what has it done for Cork city and county and what will replace it?

Arriving by train into Glounthaune station, you’re struck by just what a treasure the Cork to Cobh train line, founded in 1869, is for the eastern suburbs of Cork.

But it may become a curse as well as a blessing: the easy commuter link to the city has been used as the backbone of an array of planning applications for a quite staggering number of homes.

Glounthaune’s picturesque station house is a low, clapboard building in peeling blue and cream paint. Behind it, the magnificent trees of the Ashbourne estate, once home to brewing magnate Richard Beamish and currently in use as a direct provision centre, are swaying gently in the breeze.

From the tidal estuary waters, the calls of bird life can be heard: all would be peaceful if it weren’t for the ever-present low roar of the N25 to the South and the busy L3004. It’s only about 10 minutes here by train from Kent station.

I step out of the station and Carol Harpur is waiting: she’s a member of Glounthaune Sustainable Development Committee (GSDC) and she wants to give me a tour of the village.

Glounthaune was home to 1,440 people at Census 2016, but it’s a village in the throes of a rapid population growth, thanks in part to a series of Strategic Housing Developments (SHDs) in a variety of different stages of progress.

The building boom here is huge. In just seven years, the number of dwellings in Glounthaune has grown from 506 to 824, and there are more proposed developments on the way.

For Carol and her fellow GSDC members, more than doubling the population of the village in under a decade is a cause for concern if mismanaged. They say the infrastructure and services in the village can’t handle the increase, that new residents will find themselves car-dependent, that the village needs community amenities like cultural and sporting spaces and far else besides.

“We don’t have a master plan, or any sort of framework to get us to where we think our village should be,” Carol says as we set off on foot for a tour of the village. “Where is our vision for the future of our community? Instead, it’s all these individual packets being developed.”

Of particular concern to GSDC is an application for 201 houses and 88 apartments at Lackenroe, perched on the limestone hill to the North of the village. The application was lodged by Bluescape Ltd, registered in Ireland but seemingly a subsidiary of UK property investment firm Westhill, which had advertised a previous round of planning at Lackenroe on their website as a “residential planning opportunity.”

The application for the large development of 289 two, three and four bed units was lodged the day before the Strategic Housing Development fast-track housing scheme, which allowed developers to bypass local authorities and apply direct to An Bord Pleanála, closed.

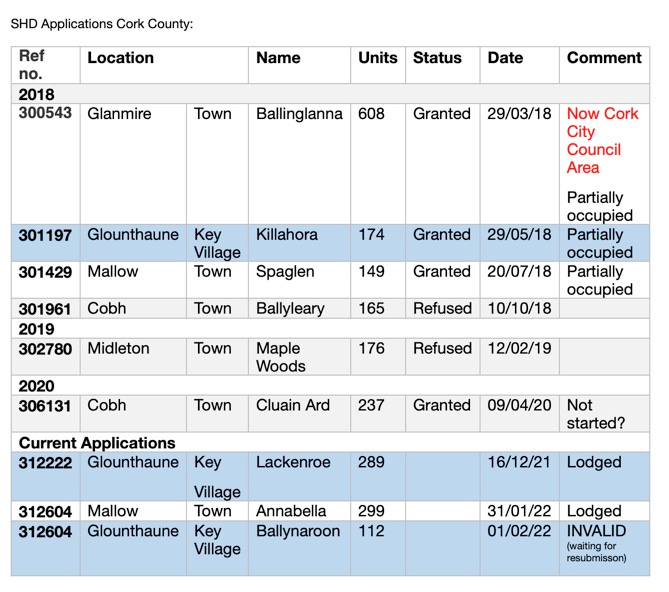

The SHD scheme is due to be replaced and developers were given until December 17 last to apply: in Cork, applications for 1,200 housing units flooded in in the week before the deadline. Lackenroe was one of these applications.

There are already 40 houses under construction at the top of the same site, purchased by Cork developers Citidwell. These are unconnected to the SHD application, whose planning documents are here.

Cork County Council submitted concerns at the SHD consultation stage where they questioned “Whether the level of residential development proposed in the settlement of Glounthaune would benefit from a masterplan led approach to ensure that such development would be sustainable with adequate ancillary social and commercial facilities, schools, shops, employment and community facilities.”

Carol and I set off for Lackenroe, up the steep hill of the Knockraha road, behind the village and under Lackenroe bridge, a protected structure. This is the vehicular access to the entire development: under council concerns about active travel access to the train station, a pedestrian entrance has been included at the front of the site close to the planned apartment blocks, but access to the houses on foot will be uphill via a long walkway of steps or a chicaned winding path for bikes, buggies or wheelchair users.

In GSDC’s submission on the plans, they make reference to the idea of “design for 30-year-old men.” Whether a mother with a double buggy, a wheelchair user or indeed a girl walking home at night will opt to use this walkway from the station, or whether more cars will be on the road running people up and down from the station - already a common phenomenon in Glounthaune - is anyone’s guess.

Radicalised by the school run

Carol, originally from Midleton, has lived in Glounthaune since 2000. As we trudge uphill towards the Lackenroe site entrance, she tells me that it was having kids - she has two boys, nine and 11 - that really brought home to her how planning decisions impact on your daily quality of life.

She’s noticed a similar trend in other Glounthaune Sustainable Development Committee members: GSDC has been on the go since 2017 and contains members from several estates in the area.

“It’s when you start going, hey, why isn’t there a proper footpath for my kids to walk on?” she says. “That’s when you start realising that these things seem like distant decisions, but that they have a huge impact on the quality of your life.”

Was she radicalised by the school run? She laughs. “I do think that’s what happens to people, yes.”

Now, she’s doing a Masters in planning in UCC and, with her husband, who comes from Glounthaune, runs a firm that produces architectural visualisations.

It’s far from an architect’s drawing that the Lackenroe site is currently. The scale of the thing hits you, the number of people who will be making this muddy site their home. They’ll be doing so at prices upwards of €330,000, if guide prices on the already sold 40 homes currently under construction are anything to go by.

Full planning for 289 units would mean an increase of over 800 extra inhabitants for the area from this development alone, and this is by no means the only development in the pipeline. Ashbourne House, at present a direct provision centre, has a planning permission in with Cork County Council for 94 houses, with a decision due for March 3, and there are serious concerns for the status of the large number of venerable trees in its grounds, some of which date back to the 19th century.

On the issue of trees, the Lackenroe application calls for the removal of 47% of the tree cover currently located on the site, including some champion trees listed by the Irish Tree Council: a full assessment of the trees and the plans for their felling are included in the Lackenroe planning documents but GSDC have expressed serious concerns about the management of what many locals feel are one of Glounthaune’s best features; the remnants of the Ashbourne Arboretum include Giant Sequioa and Monterey Pines.

On the growth of the village, though, nearby, another SHD application is that at Ballynaroon, where Ruden Homes Ltd has an application in for 112 housing units.

Carol and other GSDC members say it can’t be left to developers to profit, while the local authority and community organisations posthumously patch-fix the public, ie non-profitable, realm.

“The developers motivation is just to maximise their assets,” Carol says. “Yes, they are building houses and we need them to build houses, but there needs to be a much stronger framework from the ground up.”

Emblematic of this, she says, is the fact that the initial plans lodged for Lackenroe contained no indoor community space at all, just two ground-floor commercial units in the apartment blocks.

“They had nothing in for the community, so the council said they should use one of the commercial units as a community room,” she says. “Communities don’t have the resources to develop spaces themselves in areas like this where the land value is so high. There’s just no way that you’ll get the money to buy a site. So then it’s left to developers to develop community facilities, which is wrong, totally wrong.”

For Carol, the problems she’s seeing play out lie largely but not solely with the undemocratic effects of the SHD system, and she’s glad it’s being replaced.

The pattern, she says, is that local authorities and communities work together to produce area development plans, with lots of consultation and back and forth, and then An Bord Pleanála can force a material contravention of those local plans under the auspices of the strategic need for large housing developments.

To Carol and other members of GSDC, this flies in the face of all the hard work they do, voluntarily, to make their village a liveable, sustainable community instead of a soulless dormitory town for Cork city.

“We’ve submitted to the Regional Spatial Plan,” she says. “We’re on the ground, and we know how decisions taken up high play out on the ground.”

“With the SHDs, the decision is not taken locally: it goes straight to An Bord Pleanala and they can override your development plan. The development plan is what is agreed with the council, where communities don’t always get what they want anyway: it’s a long process of back and forth for the development plan, and then it’s agreed, and that’s like the contract with the council and that’s where you’re trying to go. But An Bord Pleanala can override the development plan and they don’t have to take account of all that hard work by all those parties, and can come in and make a totally contradictory decision.”

These criticisms are not new and are not limited to Cork, and indeed the SHD scheme has now been replaced with a new streamlining system.

Criticisms of the SHD system include the fact that they actually proved counter-productive and resulted in a huge number of costly and time-consuming legal challenges.

273 SHD applications were approved by An Bord Pleanála between 2017 and 2021, and 89 judicial reviews were taken over 74 applications.

Fears that the reform will make it more difficult for local communities to get justice in the planning system fast-tracking because the SHD system leaves the courts the only recourse people actually have.

An Bord Pleanála has put in conditions including contributions from developers, often for infrastructure or other basics. Nearby Harper’s Creek, a development of 174 units that is now in its final phase, was one of the first SHDs in the country to be granted approval, and a cycle way along the L3004, and there is also a planned creche as well as room for a doctor’s surgery.

What about cultural and community spaces, sports facilities and everything else that makes life worth living? Carol is keen to stress that GSDC are not motivated by NIMBYism: they are part of a young, growing community and that’s welcomed, she says. But the quality of life on offer has to be a good one both for existing residents and newcomers.

“You might be putting in houses, but are you building up problems for those new residents? When you can’t get a place in school for your kids? Or when you find you’re absolutely chained to your car all day long because there are no amenities or facilities around?”

Food desert?

“Where’s the closest supermarket?” I ask Carol as we stand gazing in the entrance to the Lackenroe building site. “Carrigtwohill.” “Seriously?” “Yes.” There’s one shop in Glounthaune, Fitzpatrick’s. The Aldi on the outskirts of Carrigtwohill is 4km away. There is absolutely no way that young families will be able to do anything at all other than get in a car to buy food: there is a bus link to Carrigtwohill and there are plans for a new 7.7km pedestrian and cycle route underway, but in practical terms, for many, shopping would be done by car.

Similarly, schools and sporting facilities listed in a survey submitted with the planning application are in a surrounding catchment area that extends to Glanmire, Little Island and Carrigtwohill, mostly accessed by car. And Carol says local primaries already have waiting lists.

Ballinglanna

It might be bye, bye SHDs, but their impacts on land use in Cork will be felt for decades if not centuries to come. A development of 600 homes is likely to house over 1,800 people. I wanted to see what that looked like.

So I got in my car and drove to Ballinglanna in Glanmire, where O’Flynn group are in the process of constructing 608 houses, a development granted permission under the SHD system.

At Ballinglanna, the heady thrum and whirr of building machinery fills the air….or maybe it’s the sound of money? Over 200 of the houses are complete, and moved into, but everywhere you look, you see future phases in construction. Some completed houses lie cheek by jowl alongside semi-built houses. There’s a buzz to it, an optimism, but also an eerie silence.

It’s a breezy midterm break morning, just before noon, but there’s not a soul to be seen. Some cars drive up and down the winding roads: I park up and walk, and meet precisely one other pedestrian, a teen out walking her Irish terrier. There are two cars in over half of the occupied houses’ driveways. A woman swiftly carries a baby in a car seat from car to house and disappears. I keep walking.

In the Mill View phase, compact, pleasant looking houses completed in 2019, Michael O’Connor is putting his dog in the boot of his car to take her for a walk when I stop him: when did he move in?

Michael and his wife, who have two small children, bought their home off the back of a showroom visit. “We moved in in July, during the heatwave,” he tells me.

Before they moved in, the family were living in an estate on the opposite hillside, from where they could watch the Ballinglanna development progress. “We could see these being built,” Michael says with a grin. “While we were still in the last house, I used to fly my drone over in the evenings to see how it was coming along.”

Michael works in IT in Cork City. He’s excited for the family’s future in Ballinglanna: accessibility will improve as the future phases come on line, he says: a pathway will skirt the entire development, and access will be created through the neighbouring Fernwood Estate, where there is a bus stop.

Are they pretty tied to their car at the moment? He shrugs. “Isn’t everyone with small kids? They need to do more work to the roads, definitely.” I ask him about access to shops, which he says is adequate: there’s a Lidl under 2km away and the Supervalu and Aldi are both 3km.

Michael and his wife paid €345,000 for their three-bed semi detached house, he good-naturedly reveals. But just around the corner, there’s a For Sale sign already: Joe Organ auctioneers are advertising an identical house with an asking price of €365,000.

Cllr Joe Kavanagh is a Fine Gael councillor for the Cork North East ward where Glanmire is located. He’s keen to stress that SHDs have provided much-needed homes to families like the O’Connors.

“Ballinglanna is a good project and we need housing; that’s the bottom line,” he says. “There’s a shortage. We’re going through our city development plan from 2023 to 2028 at the moment, one of three that will bring us up to 2040.”

The Regional Spatial Economic Strategy is to increase the population of Cork city and suburbs population by 55%, from 209,000 to 324,000, by 2040.

Is Joe confident that all the infrastructure and services needed to support Ballinglanna are in place? “Not fully,” he says. “All the roads infrastructure needs reform, public transport too. There’s no point living on top of a mountain outside a village if you can’t move without getting into your car. And it’s not just about infrastructure because people need a life outside of their home in terms of sporting facilities and the like.”

Joe admits that the SHD system has posed challenges for local authorities. “It is a problem and An Bord Pleanála don’t always cover themselves in glory,” he says. “Sometimes you think, how in the name of God did they come to this decision? But more recently, they are tending to go with the local authority over the applicant.”

Early in February, Leo Varadkar claimed that the scheme that will replace the SHDs, is going to be able to bridge the gap, both allaying community or local democracy concerns while also continuing to facilitate a fast-track system for what they now call Large-scale Residential Developments.

But not all parties see eye to eye on this. The recent political narrative around “serial objectors” and nuisance objections standing in the way of progress is highly reminiscent of attitudes expressed during Ireland’s last building boom. But groups like Glounthaune Sustainable Development Committee don’t consider themselves a nuisance: they consider themselves a line of defence against the worst potential outcomes of developer-led planning.

Carol, at times, sounds skeptical: “The power is on the developers side and we’d hope that the council would be the mediators to try to eke out what’s best for the place, because it really is eking it out: you’re just trying to get scraps of improvements here and there.”

However, her skepticism turns to optimism when it comes to the new bill, enacted last autumn, that will see Strategic Housing Developments a thing of the past once this final swathe of applications has been decided on. She believes the new system will weigh back in favour of local development plans.

“The LRD system will bring back decision making to a local level,” she tells me. “The local authority will better understand how well the project fits, not just at a local level, also how it fits into the cumulative development of an area, and the vision for development on a wider scale. Importantly, local authorities cannot contravene their own development plan; that’s only possible through a democratic procedure. So the importance of the development plan will be re-established, with the development plan as the binding, central element of local planning.”

“Time will only tell how this all plays out, though.”