Gone viral and going solo

Tadhg Hickey's hugely popular but polarising video sketches have marked a change of direction for the Cork comedian since his comedy troupe, CCCahoots, called it a day this summer.

It’s a summer morning and it’s raining in the park. Smatterings of fat, heavy drops fall from sodden trees.

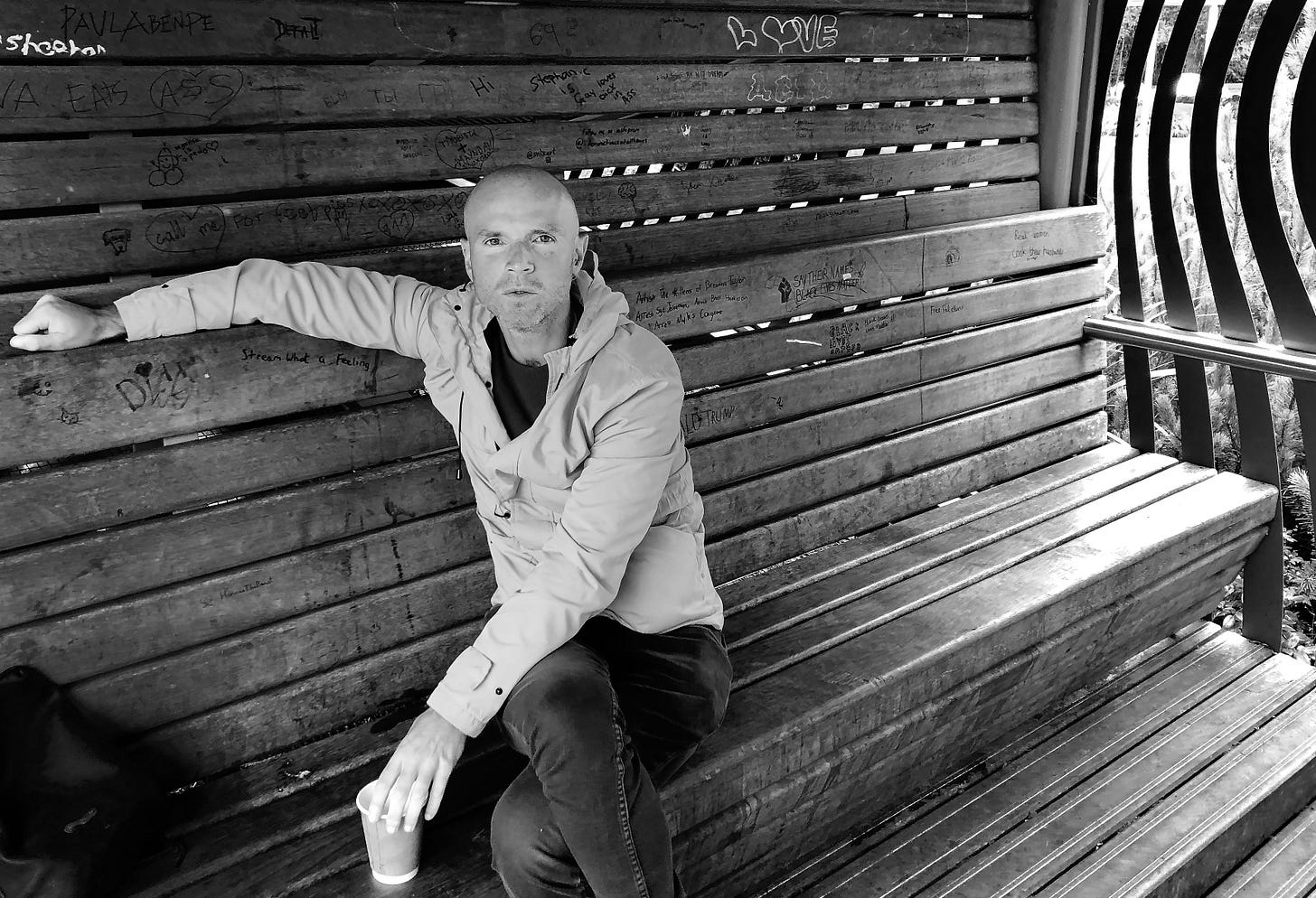

Tadhg Hickey is waiting by the café, his wiry frame protected from the elements in a bright yellow rain jacket. “Fitzies at eleven? Great,” he had messaged, when we were arranging the interview.

As we take shelter in the Sky Garden by the river in Fitzgerald’s Park, where a heron’s spear-like outline stalks the opposite bank, we agree that we are familiar to each other.

“I know your head from around the place, definitely,” he says. It’s a very small-city phenomenon that if you’re from Cork and of a certain era, you’re just…going to know each others’ heads. He’s 38, I’m 41: “We probably saw each other in Henry’s,” he says with a smile.

Of course, Hickey’s shaven head is far more familiar to me.

All year, the comedian’s razor-sharp short video sketches have been doing the rounds on social media. Pot shots at England’s inability to deal with their colonial past, at Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories, Northern Loyalists’ post-Brexit identity crisis: Hickey’s recent no-budget sketches, written in part due to the lockdown-induced hiatus to performers’ lives, have been hitting all kinds of political nerves.

Some of his sketches have well over a million views and are widely commented on, most especially on Twitter, that sparring ground for misanthropes of all persuasions. Death threats and abuse as well as adulation have followed.

Although many of the characters in Hickey’s sketches channel a distinctive, tightly coiled aggression, in person he’s relaxed and genuine, considering each question earnestly, answering with openness.

The week of our interview, he released a non-comedy project. The short film tHE gOOD oLD dAYS, directed by sound designer Cormac O’Connor, is a discomfiting attempt to get inside the mind of a character in the process of being seduced into a far-right nationalist ideology.

It’s over 20 years since Tony Kaye’s American History X made a similar, powerful foray into the world of US neo-Nazism. Like American History X, Hickey and O’Connor’s film is uncomfortable viewing, but unlike Kaye’s tour de force, it has been released in the social media era, where it seems increasingly unacceptable to recognise any humanity in those whose ideas and opinions are abhorrent to us. Where polarisation and division seem to be the outcome of our increasingly iron-clad online filter bubbles.

“Yeah, I just thought it was interesting,” Hickey says. “I don’t understand what happens in a mindset that is to some extent about patriotism and Irishness, but then is also vehemently anti-immigrant as well.

“I wanted to make something that was some attempt at getting inside the mindset of it. I don’t have any hard science to back this up, it’s just my empiricism, but some people I know who have got caught up with those groups seem vulnerable. Like myself, they might have had addiction issues, or they might have had mental health issues. So I was trying to draw a portrait of a mind that’s getting into that sort of stuff.”

It’s a departure for someone whose past creative output has been almost entirely comedy.

Best known as one third of comedy troupe CCCahoots, alongside Laura O’Mahony and Dominic McHale, Hickey wrote, directed and acted with the trio up until this summer, on projects including a 2017 three-part mockumentary for the RTÉ player called The School, and a series called (R)onanism about a man who falls in love with and marries himself.

In Cahoots no more

But CCCahoots are now a thing of the past. Not that the individual comics won’t collaborate any more; McHale is Hickey’s housemate and has been helping him direct and shoot his own videos.

What led to the split?

“The Cahoots stuff was an amazing experience, but I think we ended up trying to please a lot of people,” Hickey says. “That’s the nature of compromise, isn’t it? Our individual interests weren’t being catered for. So as soon as lockdown kicked in, Cahoots kind of finished up.”

Instead, during lockdown, Hickey began shooting his distinctive series of one-man sketches that are very much centred around his own undiluted worldview.

“I did nothing for the first month, and as soon as I pulled my head out of my arse about all my gigs being cancelled, I actually felt good,” he says. “I did more meditation than normal, and did some reading, and then I went, ‘right, now I’m going to do exactly what I want to do, because I don’t have anything now anyway.’

“RTÉ certainly weren’t interested in me: they weren’t even that interested in me when I was playing the game with them, let alone when I left the table.

“There was this kind of scorched earth feel to it, like, ‘is the arts over now really, anyway?’ There was limited support for the arts anyway, and you start to wonder if lockdown is going to be the nail in the coffin.”

Throwing caution to the wind with sketches that court controversy has garnered him unprecedented success and a whole new following. Many of his recent videos have between one and two million views, and he has launched a Patreon account where, currently, 260 followers generate him a monthly income that he supplements with commercial voiceover work.

Politics

Hickey’s unabashedly political stance is well known. He’s a Sinn Féin supporter and he has no qualms about using his online platform to encourage others to vote for the party. He’s made videos specifically calling on people to support them, most recently with his drag “Vote Lynn Boylan” video in advance of the recent Dublin Bay South by-election.

He wants it on the record that he’s never been offered a penny by Sinn Féin for his videos or social media posts.

“Yeah, when I did the Lynn Boylan one, it was like, ‘how much are you getting paid?’ I think it’s very revealing of a certain kind of centrist perspective that there has to be cash changing hands.

“That’s the void in the centrist perspective, which is that, surely this guy doesn’t actually care about social housing or a united Ireland? The centrist is always looking for the money, and I think it frightens them that some people on the Left are actually doing things, making decisions about their whole lives and careers, based on issues they actually give a fuck about. I think a lot of them are probably threatened by that.”

Sinn Féin, then, “have never asked me to do anything. I’ve done a couple of things for free for them because I wanted to, quiz nights and stuff.”

His eyes glint suddenly: “And I’d like to put on the record that if Fine Gael come calling, if the price is right, I’ll do it. I’ll make a video for them.”

Emmmm…..really? What’s his price for a Fine Gael promotional video, then?

“No, no, not really,” he says, grinning. “Not unless I could take the piss out of them.”

While his overtly political sketches and videos might be winning him an online fanbase, RTÉ television’s comedic programming tastes are nothing if not conservative: remember that even Father Ted was originally unable to find a home at RTÉ and was first commissioned by Channel 4.

But if Hickey’s political outspokenness has ruined his chances of ever working with the national broadcaster again, he doesn’t seem particularly bothered by this idea.

“In stand-up, there’s this thing where if you’re doing a stand-up show and you don’t really know another comic, you’ll almost certainly bond by talking about some scandal within the comedy community, and the second topic will be his or her experience of being let down by RTÉ.

“When we did a sitcom with RTÉ, I think maybe 70,000-80,000 people saw it the first night it came out. Twitter opens up more views for me. So you’re thinking, well, Twitter can be my unpaid RTÉ until something else comes along.

“I still want to make TV and film. I don’t want to just make sketches online indefinitely, although I still probably would because the idea of just deciding what I want to do that day, and then just going off and writing it and making it is probably the greatest addiction I’ve ever had, and that’s coming from a multiple addict.”

“Ice cream, and looking up at my dad”

Hickey grew up in what he describes as a “working-class family” of five siblings in Turner’s Cross on Cork’s south side, and went to secondary school in Scoil an Spioraid Naoimh in Bishopstown.

His earliest memory is of his dad, and of that blissful feeling familiar to any kid with siblings, of getting your parent to yourself.

“My mam and dad used to go shopping every Saturday, to Dunnes in North Main St,” he says. “My dad used to take me off for an ice cream in this shop by the bottom of Blarney Street. I was obsessed with my dad. I just loved him so much, and any time I might get with him on my own was amazing, because it was a busy family.

“So I just remember ice cream dripping over my hand and looking up at my dad like, ‘yeah. Soak this up. Ice cream, dad, summer’s day – bit of us-time. This is class.’”

Hickey’s father died when he was 18. Hickey was already drinking and partying at that stage. His alcohol and drug abuse would continue for years, eventually spiralling out of control and driving him to seek help.

“I wasn’t allowed see my daughter, I’d lost all my friends, I was close to being homeless and I was suicidal,” he says. “I didn’t realise it, because I thought I was this gregarious, outgoing person, but from 16 onwards, I would have had drink in me to meet girls, or to be funny and fit in with lads.”

Hickey spoke openly about the disastrous impacts of the loss of his dad on him, and on his journey into, and recovery from, addiction in a candid interview on The Two Norries podcast last December.

He’s obviously adopted a policy of talking openly about his addiction, but surely this can’t always be comfortable?

“Well, I actually think I got the balance slightly wrong in that interview when it came to talking about my family, because it’s nothing to do with them,” he says.

“If I could just talk about me, and it was not connected to my family and the people I’ve hurt, I could chat about it all day. I’ve gone through it all, and I’ve made my amends. Some have been accepted, and some haven’t, and I generally feel ok about myself today.

“So I’ll chat away about myself, but you don’t want to keep fucking bringing it up if, say, you’ve hurt an ex-partner and they’re going, ‘this guy’s fucking using me for material again.’ I don’t want that. it’s very hard to talk about your story and have it not involve other human beings, though.”

Meditation

With the aid of transcendental meditation, Hickey began his recovery process. Now, he says he hasn’t had the desire to drink in about five years.

He meditates twice daily, morning and evening.

“For me, just to stop drinking when it had been my anaesthetic for I don’t know how long? I’m not going into detail with my recovery stuff, but my head was just gone,” he says. “I was in a state of soft panic all the time.

“It was the most grief I’d ever had in my life: it was like, it’s gone; drink was my forever friend and it’s gone. That was the painful stuff. The meditation was not painful at all. It just brought in this stillness. In that stillness, you feel like your mind and body are healing, like you’ve just plugged yourself in. That’s what it’s like: a mechanism to bring yourself into deep rest whenever you want.”

I tell him I’m scared to start meditating, scared of the things it would dredge up if I switched off the “monkey mind” and started looking around inside. Because to be honest, it’s an infrequent occurrence to meet someone who seems as genuinely ok with their baggage as Hickey is, and I’m certainly not.

“Yeah, the monkey mind feels great: you’re writing things and making sketches and battling people on the internet,” he says. “But you don’t actually want to be there. Really, you want to be in a state of deep rest.

"When you’ve been meditating for a while, the idea of going drinking for days on end in a gaff somewhere and missing work just starts to seem like a really bad idea. You just start thinking, ‘Your body’s going to feel like shit, you’re going to be depressed for a few days, and all the people you care about are going to be wondering where the fuck you are.’ You just start to think, no, that would be a bad idea. It doesn’t turn you into a saint, but the things that are contrary to the things that are going to make you feel good about yourself in your spirit just tend to…go.”

The impacts on his creative output have also been profound: his work ethic is partly driven by a desire to make up for the time he lost to addiction, he says. And the life he has built for himself since he began his recovery process is, by all accounts, pretty fulfilling.

“Yeah, in the depths of it I would have thought the life I’m leading now was a fantasy,” he says. “When I first came around and people were saying, ‘oh you’ve a great life ahead of you, without drink your life will be great,’ I was thinking, ‘well, these people are just making the best of what is a horrific life sentence for me now. Which is that I can’t drink. My life is going to be not only boring, but intensely socially awkward.’”

Online threats

Hickey has found himself on the receiving end of some pretty obscene online abuse recently, including sexual threats against his deceased mother.

Inexcusable as such extreme behaviour is, some of Hickey’s own Twitter followers are not averse to a little trolling, and some of his sketches, including his 12th of July sketch in which King Billy comes back from the dead as a flamboyant, gay Republican to set the record straight, are arguably themselves a form of trolling.

Does he ever worry that he’s actually fomenting division? After all, if a 32-county Republic comes to pass in our lifetimes, Ireland will find itself the home to a small, angry minority: shouldn’t we be trying to heal the rift and reassure them that there’s a place for them in a new Ireland?

“I feel the tradition I’m attached to, an Irish Republican tradition, is the minority,” he says. “We are the oppressed in that particular paradigm. And it’s always been the role of the oppressed to use humour like that: slaves used satire to take the piss out of slave owners. We have better control over the satire narrative.”

“Having said that, I’d like to reach out to loyalists and I’d like to find a way to take the piss out of my own side a bit more.”

He admits that the online abuse sometimes gets to him, but that, rather than being an attempt to orchestrate a Twitter pile-on, him retweeting his trolls with humorous commentary is therapeutic, and also a successful way for him to generate online engagement.

“If someone says ‘I’m going to burn your house down,’ and I retweet it saying, ‘joke is on you mate, I live in an apartment,’ I feel like I’m bringing some lightness and levity to a dark situation,” he says.

“When the first Loyalism video went out, I was getting a lot of comments that were just off the wall: ‘This is akin to blackface.’ ‘you’re taking the piss out of my culture.’ I was getting all these retorts, and I was getting a kick out of them, and the numbers were going up as I was replying to them: now that’s addictive. That’s fucking seriously addictive. I definitely got hooked, and that’s not sustainable.”

Social media: a new addiction?

Tech developers for social media giants have come clean about the extent to which push notifications such as “like” and “scroll-to-refresh” functions are purposefully designed to be physiologically addictive.

Is he ever worried that he’s swapped out one kind of addiction for another? He looks thoughtful.

“I’m definitely on Twitter too much,” he says. “Without cracking out the violins, it’s stressful enough because people are asking me to do things all the time: I’m ostensibly a hard-ass, but I’m actually really soft and if people are getting on to me asking me to share stuff, I generally do, or I’ll read about what they’re doing. But the numbers got so big so quickly that it’s a lot and it can be quite stressful.

“I’d love to build something where I’m making videos and putting them out once a week, and going online every couple of days to check how they’re doing.”

Back to live gigs

After such a long hiatus, albeit one that has brought him a whole new level of success, Hickey finally has a live gig to look forward to: he’ll be performing his one man show, In One Eye And Out The Other, as part of The Everyman Outdoors, a series of outdoor gigs at Elizabeth Fort, on July 31. And before you ask, yes, it is already sold out.

It’s a show he has performed before: prior to the Covid crisis, he had performed it in Dublin’s Smock Alley and at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival.

Lots of performers are going a bit stir-crazy and are desperate to get back to live audiences, but not so Hickey, he says.

“I wasn’t whiling away my time in lockdown going, ‘I can’t wait to get back out there,’” he says. “I’m not that type of comic that’s got to have an audience in the room, has to get that laugh. If it doesn’t sound too pretentious, I just want to make strong work. That’s always been the dream, and I feel like it’s really just in the last while that I’ve stumbled upon a means of doing it consistently.”

He’s got other plans in the pipeline, including some things he’s not willing to discuss because they are in their infancy, but there are hints at a promising UK conversation. He’s been writing a feature-length film script.

How ambitious is he? He says it’s an uncomfortable question to answer: in Cork, we don’t like admit to too much ambition.

“People are squeamish about ambition here, I think,” he says. “We’ve got a begrudgery thing going on. The key trolls I have on Twitter? They’re all from Cork. I’ve had ‘he’s an embarrassment to Cork’ I don’t know how many times.”

“I don’t feel like I have a massive ego. At least I don’t think I do, but maybe we all think we have it under control. But I’m not going around at home going, ‘I’ve made a great sketch” and high-fiving people.”

He is ambitious, though.

“I just want to make stronger and stronger work,” he says. “My ambition is not about being on telly in particular, it’s just about the quality of work. Now I feel like I can nail down potentially complex ideas into small scripts, so, can I do that in bigger scripts?”

“I think I’ve figured out what I’m able to do, and I’m good at it, and there’s an audience for it, and I’m able to work every hour God sends because I’m a workaholic, on top of everything else.”

Hickey became a father at just 21. Recently, he’s been roping his daughter, now 17, into helping him film his sketches.

At the end of our interview, with the rain still plopping steadily on the surface of the calm, green Lee, before asking him to pose for photographs, I ask him one last question. It’s one that sometimes works and sometimes doesn’t. Some interviewees wriggle in discomfort when asked, some trot out something that sounds like what they think you want to hear.

Rapid fire: what’s the thing in your life that you’re proudest of? Only the merest of pauses.

“I’m proud of the part I’ve played – and mostly that was just surviving – in the person that my daughter has become,” he says.

“She’s just a balanced 17-year-old who is fantastic to be around, and she has an awful lot of empathy. She lives with her mam, and so for some of lockdown I couldn’t see her because she’s just by the book, not like I was at her age at all. And that was really hard.”

“The person she’s become, I feel like I must have done something right, even if the only thing I actually did was just not letting addiction suck me into the ground.”

Love the in depth interview

Such a change from the usual