Glyphosate: Time to ditch it?

An "absence of policy" at county council level and mounting resistance to its use in the city: is our weed control out of control in Cork city and county?

Ballincollig: the “spray-free” town that just got sprayed

“It’s disheartening, and it’s very disappointing,” Tom Butler says over the phone.

Tom is a member of Ballincollig Tidy Towns. You’d be hard-pressed to find a community group more active than Ballincollig Tidy Towns (BTT); they are the proverbial busy bees when it comes to improving their town for its 20,000 inhabitants. They arrange planting schemes, litter picks and maintenance. They’ve recently helped to arrange the installation of a ‘parklet.’ Each year they enter the national Tidy Towns competition.

One of their proudest achievements has been their Ballincollig Pollinator Corridor, which extends from the Poulavone roundabout right the way through Ballincollig: pollinator-friendly planting schemes and a spray-free policy.

“The idea behind our pollinator corridor is that bees and other insects can go right through Ballincollig, feeding as they go,” Tom explains.

I had called Tom because I wanted to include Ballincollig as something of a gold standard in Cork City and County.

For months I’ve been researching the use of glyphosate by Cork’s local authorities, and many people had pointed out Ballincollig’s enlightened no-spray policy, which they launched in 2020.

Why no spray?

There’s a global biodiversity crisis facing pollinators including bees, butterflies and other insects. In Ireland, 30% of bee species are endangered. Pollinators are necessary for many of the crops we grow for human consumption. In Europe, 84% of the most important 264 crops are animal-pollinated, according to the National Biodiversity Centre.

Already, one of the most worrying phenomena impacting on honey bees in recent years, Colony Collapse Disorder, has been linked to one class of pesticides, neonicotinoids.

Glyphosate, the active ingredient in Round-Up, is the most-used pesticide on the planet. It’s widely used in agriculture (you can listen to my podcast on agricultural glyphosate use here), in private homes and on public land for weed control.

It’s been shown to be toxic to bees in numerous independent studies, with impacts on pollinators’ gut health, navigating abilities and the growth of bee larvae. It has well-documented toxic impacts on aquatic life, and fears that it’s also a carcinogen for humans have been mounting.

In June 2020, Bayer, the giant multinational chemical company that owns Monsanto, Round-Up’s manufacturer, settled an astounding $10 billion in a US class action lawsuit where tens of thousands of groundskeepers, gardeners and farmers said Round-Up caused their non-Hodgkins Lymphoma.

Cork city council sprayed Ballincollig anyway

Cork city council workers, some time within the past two weeks, drove through Ballincollig on a quad and sprayed the verges and the bases of trees with glyphosate.

Tom doesn’t want to appear critical of Cork city council: he’s keen to stress that BTT work in an atmosphere of “mutual respect” with the local authority. The situation is being followed up and keeping good communication going is important, he tells me.

“What’s happened with the spraying is extremely disappointing, but hopefully we can turn this negative into a positive,” Tom says. “It’s a glitch, but hopefully we can get it sorted and hopefully it will never be repeated.”

Still, his frustration is palpable.

“We submitted our application for National Tidy Towns last week, and now we have to write to the adjudicators and say, look, a lot of what we said in our application has been undermined,” he says. “We have to make them aware in case they did come out to us, because we’d look like liars.”

To Tom, even on aesthetic grounds, glyphosate use for weed control doesn’t make sense. The tell-tale dead brown foliage along kerbsides, around lamp posts and park benches is not an improvement on longer growth, he says. It’s a matter of changing mindsets, both within local authorities and in the minds of the general population.

“People really need to wake up,” he says. “We went to Europe for the Entente Florale competition in 2016 and saw 12 other countries and what they were doing. We are so far off the mark in Ireland. We have to start thinking outside the box. Grass doesn’t have to be a croquet lawn all the time.”

Over the other side of Cork city, Independent county councillor Marcia D’Alton has had experiences every bit as frustrating as Tom’s.

A member of Passage West Tidy Towns where she lives, Marcia, a former environmental consultant, recounts to me an incident where the community group had planted boxes of petunias in time for the annual competition.

“They were flowering and the council came along and sprayed the kerb edge; there was a breeze, and it drifted, and it killed the entire flipping lot,” she says. “That was frustrating, but we got over it. What was really bothering us was the excessive spraying, sometimes a foot wide, to control growth onto paths and that kind of thing. We wrote to the area office two years ago, and asked them to stop spraying and got no response, but there’s been no spraying since and we started managing it ourselves.”

Marcia points to the many positive moves that have been made to reduce spraying: Midleton, in the East Cork Municipal District, drew up a local pollinator plan for 2020 with minimising spraying at its core, and Carrigaline has followed suit.

But when councillor Diarmaid Ó Cadhla called for a county-wide ban of glyphosate at a council meeting in March 2019, Marcia found herself weighing up the practicalities of an outright ban.

“I strongly supported that we would have a policy on its use, and that we would minimise the use,'“ she says.

Glyphosate is used to eradicate Japanese Knotweed, a persistent invasive species across Cork county.

Marcia is aware of the complexities of the situation: across both Cork county council and Cork city council, weed management is largely undertaken by contractors, but most housing estates are managed by residents’ associations who arrange their own area upkeep.

“It might be €40 per year for a household to contribute to the residents’ association,” she says. “While I hear a lot of queries about glyphosate and while the public is getting more interested in the issue, sometimes if a residents’ association seeks to maintain their area with manual labour instead of spraying, this can push that contribution up, to as much as €80 per year. That’s the point at which some people lose interest.”

What Marcia wants to see most is a proper, county-wide policy on glyphosate use: detailed record-keeping, she believes, will concentrate the minds of local authority staff and change how they interact with contractors.

In the Freedom of Information request I submitted to Cork county council for this article, the biggest thing I uncovered was arguably precisely this lack of any coherent policy.

Cork county: an “absence of policy.”

Cork county council is the biggest Irish local authority in charge of one geographical area: from the toe-tips of the Beara peninsula to the borders with Tipp and Waterford, it’s a vast administrative area, made up of eight “Municipal Districts” with 21 local roads offices.

I asked to see all communications - internal, and with contractors - for 2019-2021, under AIE (Access to Information on the Environment) legislation. AIE is FOI’s big brother: underpinned by the Aarhus convention, it’s based on the principle that all EU citizens should be able to access information on their environment, for free.

Of eight Municipal Districts (MDs), only three return any information to me. Only one has any detail. When I query the inconsistencies of the return, the AIE officer explains that “in the absence of any policy,” each MD basically operates spraying programmes however they see fit.

Show….me….the….money: €80,000 across Cork county?

The first thing I really wanted to know was the annual spend across the county: I already know Cork county council can’t furnish information on the quantity of glyphosate used managing public land, because it’s largely contractors doing the work.

My return reveals that the roads executive of Cork county council estimates an €80,000 per year spend on “weed control,” and that the Chief Executive is “happy to continue using the product in compliance with safety data sheets.”

According to another document, one contractor is paid €21 per km per application in East Cork Municipal District, with spraying conducted three times annually. A representative of Weed Control Ltd, the contractor, said in an email thread this March that the “season begins shortly.”

But East Cork MD also includes Midleton, where one particular member of council staff has been instrumental in pushing for change on glyphosate use. Emails in a thread seen as part of my return highlight this individual employee’s action on the issue from 2018 onwards. In 2019, the staff member wrote:

“Our extensive use of, and dependency on herbicide/Glyphosate is a major concern to me as we should be protecting our pollinators. Also, an MD using Glyphosate in a Karst limestone region where drinking water is abstracted from aquifers is really troubling. Our current default position of ‘Spray it’ needs to become our absolute last option and not the predetermined action.”

In West Cork, where a separate contractor is hired for spraying, in 2020, the only communication in my return is an email from the contractor to a council staff member reading:

“Spraying at Crookhaven all done weeks ago. I'll send invoice over shortly. Any joy on signs for knotweed? I have also invested in a new quad and spraying boom of 3 mtrs and lance if you have any other areas that need one off or regular treatment.”

More Freedom of Information: 158km of North Cork spray-zones

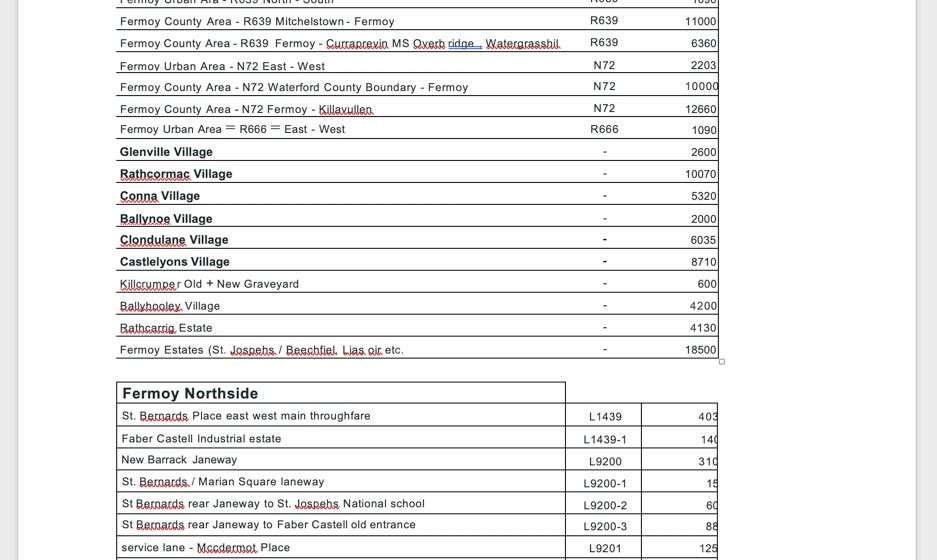

The only detailed records returned are for Fermoy Municipal District, who send a form for a spraying programme for 2021 extending to 158km, including individual listings for estates, secondary roads and villages: 7km of spraying through Kilworth village, 10km in Rathcormac etc. It’s the same contractor as for East Cork: at the same rate, this would mean Fermoy MD is spending just under €10,000 per year on spraying.

If you live in North Cork and want to see if your street or village is listed, I have made the entire document available in my occasional FOI data dump here.

Dr Lucy Weir lives in Kilworth, has a PhD in environmental philosophy, and is a member of environmental group North Cork Forum. I send her the document and then call her: how did she feel when she saw it?

“It’s shocking,” she says. “This is unacceptable; it’s really a dinosaur age approach, with the knowledge that we now have about the impacts of pesticides. I think it’s really wrong-headed and that they need to update their policies urgently.”

“It’s also in direct contravention of Tidy Towns, and the crazy amounts of money being spent to protect biodiversity. It’s like, the right hand doesn’t know what the left hand is doing.”

Why does it matter if we don’t know how much glyphosate is in use?

Local authorities are only one of the entities using glyphosate. They are not the heaviest users. 240,000kgs of glyphosate is used annually on Irish farms, according to an estimate derived from the most recent research from the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine.

Coillte are another large player. Private businesses with a large footprint, such as pharma, are too. As are home gardeners: Round-up is brand leader in large garden centres.

The reason why it matters if we don’t know how much is out there is down to exposure levels, for both animals and humans. For example, Lucy lives in an agricultural area, that’s also in a Municipal District with an extensive spraying programme, and lots of Coillte-managed woodlands around.

Glyphosate, in Round-up or other proprietary applications, comes with a safety data sheet which specifies that glyphosate is toxic to aquatic life-forms with an instruction to “keep out of drains, sewers, ditches and water ways.” Spraying is not recommended in wet or windy weather. But it still ends up in water courses and sometimes, drinking water supplies, both nationally and in Cork city and county.

The Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine began a national survey of Local Authorities to examine the scope of non-agricultural glyphosate use in 2018.

Before I speak to Lucy, she sends me images of Glensheskin wood, close to her home, taken at the weekend, that speak to the complexity of the overlap between different entities that use herbicides.

“It had been raining hard and in the woods, there was a sign warning people not to forage as the area had been sprayed,” she says. “This is within the catchment of the stream that feeds the reservoir. I realise this is Coillte land, and not the council, but the council is responsible for the protection of the reservoir.”

Lucy wants the routine use of glyphosate for roadside maintenance and weed control phased out quickly by the county council.

“I think we need to update policies as a matter of urgency,” she says. “I cannot stress, having done research in the area of biodiversity loss over the last ten years, how scared I am at the current rate of decline. I don’t want to scare people, but when you see something like this from officials who are using my money to essentially fund ecocide, that’s the point at which we really need a slap in the face to wake us up.”

An All-Ireland Pollinator Plan: greenwashing?

Ireland’s first All-Ireland Pollinator Plan 2015-2020 was heralded as a great success, and a new and expanded AIPP 2021-2025 has been launched. Much of the positive action mentioned in this piece derives from the awareness created by the first plan.

But if it allows corporate partners and local authorities alike to trade on a green image by being “pollinator-friendly” without committing to quitting spraying, is it actually a form of greenwashing? Last winter, Cork County Council announced pollinator plans for six Cork towns…including Fermoy, which as we have seen, executes an extensive spraying programme.

What point is a bee hotel or a no-mow strip if you haven’t gotten an organisation to commit to stop spraying a chemical that is sickening pollinators?

The AIPP 2021-2025 is remarkably low-key in its mention of pesticides: of eight actions aimed at local authorities, there is one mention of pesticide reduction: most focuses on branding materials, web resources and awareness campaigns.

Cork City

Back in Cork city, where the council contracts out management of 500km of roadside maintenance, Ballincollig’s spraying debacle is not the only issue this summer.

One resident of the Blackrock/Ballintemple area who wishes to remain nameless has documented glyphosate spraying along the Marina this summer. Trails of dead brown grass, right along the waterfront. In a previous year, this resident objected to Cork city council’s spraying programme in the housing estate in which he lives.

The response he received from a council staff member said “we use specialists who have up to date training and certification from government departments in order to minimise risks. There is no benefit to trained operators spraying where there are no weeds – it is completely ineffective and is a waste of their money. So there is a specific incentive that they only apply treatment to existing weeds.”

The photos captured by others on social media this year don’t exactly speak to dedicated specialist expertise either, to put it as politely as possible:

County council and city council executives make frequent reference to safety measures in defending their contractors’ use of glyphosate, yet waterfront spraying is specifically precluded in the safety data sheet I linked above.

I asked Cork city council for a response to the Marina park spraying, which extended right down to the edge of Atlantic Pond.

“This area was sprayed in error due to a procedural oversight,” a PR spokesperson said in an email. “Strengthened measures have been put in place to ensure that such an error does not recur. Cork City Council policy is not to spray near or adjacent to waterways.”

But the Lough, too, has been sprayed right up to the waterside kerb this year:

Should local authorities prepare for a glyphosate ban?

Both in local authority and agricultural use of glyphosate, the Irish argument is that the pesticide is not replaceable.

At an EU level, in the face of mounting evidence of harms to pollinators and human health, and with the spectre of the precedent set by US workplace exposure lawsuits looming, the appetite for glyphosate is waning.

In 2016, a poll in five EU member states found 66% of respondents wanted a ban on the pesticide. In 2017, when glyphosate’s last licence expired, member states voted not to extend the licence for the customary ten years, but for five, subject to a stringent renewal process that is expected to conclude this September. Several member states, including Luxembourg and France, have already begun to institute partial or full bans.

So why is Ireland dragging its heels? The answer comes partly with our strong farming lobby, but also with difficulties in replacing entrenched mindsets and working practices. As Marcia had pointed out, navigating the terrain of the hard work of others is a sensitive business.

I wanted to conclude this article on a positive note.

In Cork city council, two pilot areas - Fitzgerald’s Park and Shalom Park - are now managed with an organic, vinegar-based herbicide, with a view to phasing out all herbicide use in amenity areas within the next five years.

I wanted to interview the Parks and Rec department on this development, but unfortunately, no-one was available. The PR department sent me the following update:

“Cork City Council is working towards the zero use of herbicides in all our amenity areas within a three to five year period. We have made some significant strides forwards towards this goal in recent years and continue to move this project forward. For example the City Council is presently involved with a body of research with Maynooth University looking at alternative methods to the use of herbicides.”

Policy…and a little opinion

Individual positive moves, and the actions of people with a particular interest in areas like Midleton, Ballincollig and Carrigaline, can make small, incremental steps towards replacing unnecessary glyphosate use.

But unless we know the extent of its use, we clearly can’t even come to grips with managing the actions of private contractors, as we’ve seen with out of control spraying in the city this year, not to mention get a clear picture of how much glyphosate local authorities are adding to the overall volume of this substance in use.

So I’m going to end this article with a little opinion.

Mapping tools now provide a fantastic facility for councils to engage with the public.

Fermoy Municipal District fill out a detailed form of everywhere they are spraying: no matter what we think of the extent of their spraying, their action in recording it is to be lauded. In fact, my big ethical dilemma with this piece was whether publishing their form would actually disincentivise a type of record-keeping that needs to be replicated by every MD.

A county-wide map, accessible to the public, of where spraying programmes are carried out should be built, with each MD responsible for uploading their plan annually.

As Marcia said, this would “focus the mind” of council staff responsible for tendering. It would add to the sense that we all have the right to know what’s happening in our local environment, be that concerned parents in estates, or Tidy Towns groups who have worked long and hard to avoid spraying.

Last but not least, it might incentivise local authorities to prepare for a future free of glyphosate, be that when the EU licence expires, or when a critical mass of people who believe in alternatives is reached.

Detailed and informative article. Really important read for anybody using parks and walkways. The research is thoughtful and in depth, just what we need!