From butter to bytes: recreating Shandon?

Plans to convert Cork city's Butter Exchange building into a tech and job creation hub have been lodged with Cork City Council, but some say the building is better used for tourism or culture.

All butter roads lead to Shandon

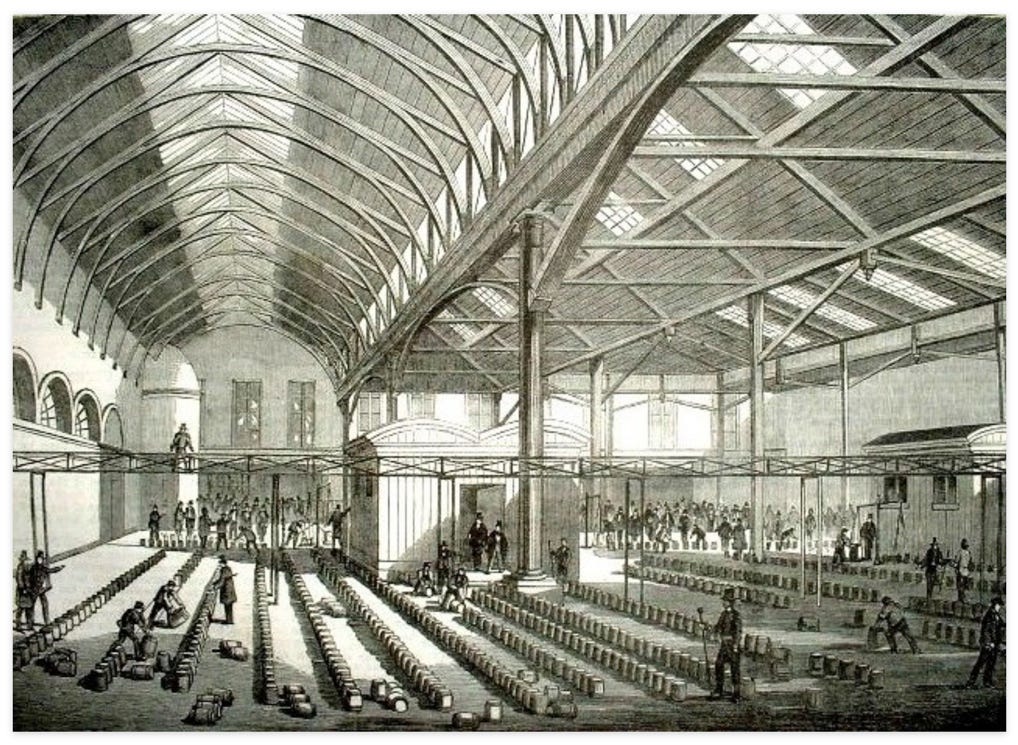

Standing in front of the imposing portico of Cork Butter Exchange in Shandon, it’s tempting to take a moment to imagine stepping back in time 160 years, to the hustle and bustle of trade in the building’s heyday, when it was the largest such enterprise in the world.

428,000 firkins - small barrels - of butter were exported from Cork in 1858. A constant flow of farmers and brokers arrived to the Butter Exchange building both day and night, because it operated 24 hours a day. Each firkin was graded for quality and weighed, and then exported to the four corners of the empire Ireland was then a part of.

Those with butter to sell arrived via the network of Munster butter roads that stretched far beyond Cork county, as far away as Castleisland in Kerry.

The noise and smell would be almost unimaginable to us in our modern, developed-world lives; the Butter Exchange was located in what was also then Ireland’s largest Shambles, or outdoor livestock market. It’s said that at times, the blood from slaughtered animals would run all the way down to the Lee.

Inside the cavernous hall, clerks rushed about marking grades on Firkins with chalk, coins chinked and voices no doubt occasionally raised.

Butter trading at the site actually started in the outdoors in the 1770s, and grew and thrived until, in 1849, the facade familiar to us today was built. It was designed by Sir John Benson, who also designed the Waterworks on the Lee Road, St Patrick’s Bridge and the Prince’s St entrance to the English Market.

On the day of my visit, the building stands in darkness and silence.

The gates are bolted and the only sign of movement is from the many pigeons that make the portico their home.

As I take photos, a family group of tourists wanders past. One young woman points towards St Anne’s and the iconic salmon weathervane. Her mother pauses and gestures towards the Butter Exchange. “But I guess this is probably an important building too, huh?” The family gaze at the building briefly, and walk on.

Following the collapse of Cork’s butter trade during the latter years of Ireland’s inclusion in the British Empire, the exchange closed its doors in 1924. It was sold and converted to textiles manufacturing, first to Sunbeam Wolsey and afterwards to O’Gorman and Sons’ hat factory. In 1976, the building burned down, leaving only the portico and exterior walls.

Cork City Council, then Cork Corporation, bought it and rebuilt it, and converted it into a craft centre in 1984. But over time, problems including a persistently leaky roof and an apparent dispute between the tenants and the council led to it being shut for increasingly long periods of time.

In recent years, the only use of the building has been as a temporary lair for the Dragon of Shandon in the lead-up to the night-time parade each Halloween.

From butter to bytes?

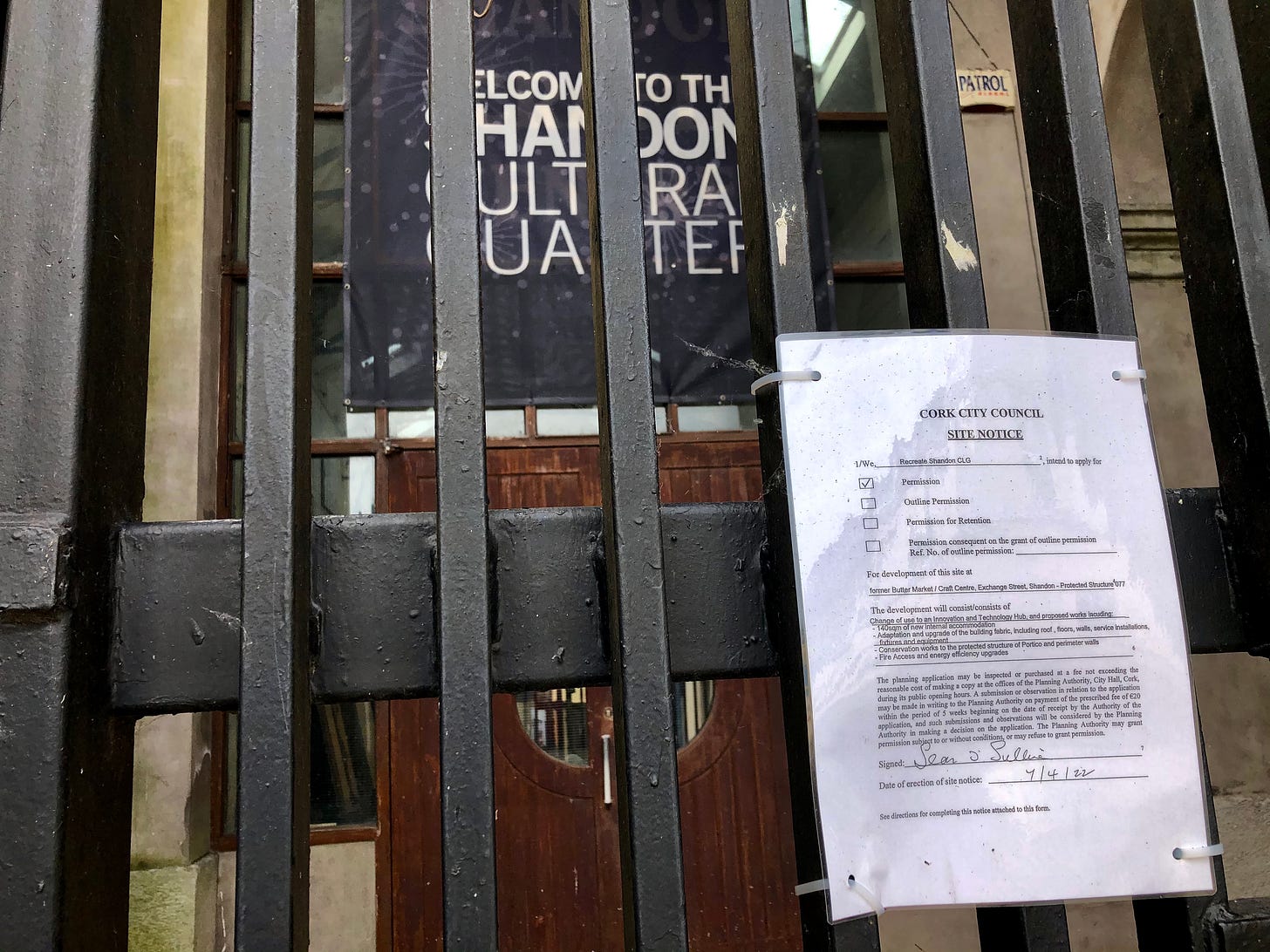

On the gate of the Butter Exchange, there’s a planning notice. A planning application for permission to convert the building into a technology and innovation hub called Shandon Exchange was lodged with Cork City Council this April.

The plan involves minimal disruption to the exterior of the building, but inside, a multimillion euro steel-framed development would see the building home to 13 co-working offices, two meeting rooms, a canteen and a lift to provide access to an upper floor.

The Shandon Exchange website is high in buzz words like growth, innovation and outreach, but low on detail; a funding page contains one paragraph saying that Shandon Exchange is a not-for-profit that will rely on private donations and funding schemes including the Regional Enterprise Development Fund.

€1 per year for 25 years

Last September, Cork City councillors voted to dispose of the building by lease to Recreate Shandon CLG, the company founded in 2020 by Cork entrepreneur Seán O’Sullivan, for the nominal sum of €1 per year, for 25 years to facilitate the tech hub plans.

Mr O’Sullivan is the Managing Director of Seabrook Technology, a Medtech Company that digitises processes for orthapaedic manufacturers. Seabrook Global is based in both Ireland and in the US in Pendleton, Indiana, and the promise of US funding for the Shandon Exchange project has been mentioned repeatedly.

Other listed members of Recreate Shandon CLG include former Cork University Hospital CEO Tony McNamara, who now runs a business consultancy called Insight Management Consultancy, and William F Plunkett, a New York based attorney and real estate advisor.

The clock is undoubtedly ticking on the Butter Exchange building in terms of state of repair.

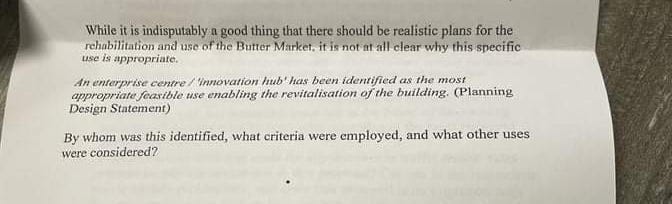

Cork City Council’s executive have represented Recreate Shandon CLG’s tech hub plans as the only viable proposal that can restore the building to its former glory and inject some much-needed vitality into Shandon, an area steeped in the finest of Cork city’s culture and history.

But not everyone agrees. And a tech hub was not the only offer on the table, by any means. Several organisations and individuals had expressed interest in the building.

Shandon’s cultural potential: “The Montmartre of Cork”?

David McCarthy is the current director of the Camden Palace Hotel, the community arts organisation that was housed in the former MacKenzie’s Garden Centre on Camden Quay until 2016. Camden Palace Hotel was a meanwhile use project, and always knew they’d have to leave the ramshackle but palatial environs of the landmark quayside building.

It took until last year for developers to lodge a planning application for an actual hotel on the site of the former arts venue. The Camden Palace artists had moved into a temporary studio on John Redmond Street, which they also had to leave in 2017.

Camden Palace was invited by Cork City Council to make an expression of interest in using Cork Butter Exchange in 2016. David McCarthy was one of the Camden Palace board members who put together the proposal.

“We had a fantastic plan for it,” David recalls, “We were going to model our engagement with the local community on Montmartre in Paris. The place is very richly served with artists who live in the area. We were going to double or triple the time that tourists would spend in the Shandon area, because at the moment they just go up, look at the clock, and come back down again.”

“We were going to have a café for visitors, we were going to have a printing press which would produce saleable items like greeting cards and produce marginal income for artists in the area. There was going to be performance space; there was a whole raft of stuff and it was quite an exciting proposal.”

Camden Palace Hotel were also willing to provide a publicly accessible toilet for visitors to the area, something which the area currently doesn’t have, as well as a café in the back of the building.

Having drawn up a detailed proposal and made a presentation to several Cork City Council executives, the Camden Palace hopefuls simply…..never heard back from the council again. Even, David says, when they sent follow-up emails to various council staff asking for feedback and news.

“They said thanks, that’s all very interesting. And then we never heard from them again, not even when we prompted them. We never even got an acknowledgement. It deflated us, and it kind of damaged us a group.”

They found out about the tech hub plans in the local paper.

“It all came to naught in the most mysterious way,” David says with a sigh. “It was like….losing a telephone connection, you know? And it was very disheartening because we had put considerable time into the submission, all voluntary of course.”

By all accounts, there was a fairly serious lack of alignment about the amount of money the renovation of the building would take. Camden Palace were a shoestring organisation with no public funding who prided themselves on their DIY, non-monetised approach. Then-director Bertrand Perennes thought the building could be made safe and usable for €40,000.

“City council came back with a figure of over a million,” David says. “It included the removal of the Asbestos roof. Bertrand was of the opinion that the council was trying to get someone else to do their restoration work for them.”

Camden Palace remain homeless and searching for a permanent home ever since. A large city centre space, open to the public, where creative people can engage in spontaneous cross-pollination, something to replace their original location, is what they still seek. The exciting buzz of an active, inclusive arts community in the city centre is an irreplaceable asset to the city, David believes.

“When you have a centre like that available to creative people, you draw together people who don’t belong to the same creative genre but who feed off each other and collaborate each other and support each others’ work: we had a group of photographers work with a dance school, for example, to produce a photographic exhibition that was itself a work of art. That sort of synergy was so commonplace. All of that happens when there’s a space that allows it to happen and you don’t have to plan for it. Without a place for people to come together, it can’t happen.”

A new City Centre Development Plan

Back in 2017, I was writing about the pattern of closure for arts organisations and venues because a palpable trend was underway.

Sample Studios, Cork Community Printshop, The Camden Palace Community Arts Centre, Mad About Cork, The Kino, The Pavilion: in just over a year, a spate of closures and evictions happened that had a profound impact not only on arts and entertainment workers in the city, but also on the cityscape itself.

Most of these buildings remain empty to this day, bar the former tax office that housed Sample Studios, where 86 artists had studios and where a massively vibrant scene centred around classes, workshops had been built.

That building was knocked down in 2018 to make way for a planned four-star hotel, but remains a pile of rubble behind hoardings to this day.

Five years later, the impact of this brief period of time can still be felt. The thriving scene that had been developing in the plentiful supply of often semi-derelict city real estate has partially evaporated.

Instead, corporate space is dominating our city. Offices, offices and more offices in just about every key location in the city centre, despite a post-Covid flexible labour market that now no longer requires offices. Despite an absence of homes for all these putative new workers we seem to be planning for.

But a new draft City Centre Revitalisation Plan, drawn up by accountants KPMG, was presented to Cork City Council this week and puts arts, culture and the “night-time economy” very much front and centre.

It recognises that space for arts is a barrier to the city’s development, and even begins to propose the kind of meanwhile use that Camden Palace and others had naturally operated. .

“Proposals to develop a cultural centre and/or creative makers hub could result in a strong uplift in cultural capital and spillover job creation,” part of the report reads. “Such a space would be multi-use, with modular seats/a modular stage, with space for public engagement: performance, multi-media, education and engagement, cultural business, hospitality, creative production.”

“The cultural centre could be located in the City Centre, with spatial linkages to the quays, which has the potential to become a key area for entertainment and restaurants.”

A key action identified in the report is to “develop local community-led public arts programmes to grow identities of areas, working with community and creative groups.”

What benefits will a tech hub full of co-working spaces, essentially offices, bring to Shandon? Will tourists and the general public be able to access this historic building and its walled garden?

The planning application’s archaeological survey uses the phrase “rental accommodation for business start-ups” to describe the proposed 13 co-working spaces, which raises another concern: will spaces in the hub be free, as some form of bursary, or will they be rented, in which case, why does Recreate Shandon CLG get the benefit of a free 25-year lease?

And what checks and balances are in place to stop Shandon Exchange from just becoming the most prestigious offices in the city?

I wanted someone to talk me through the benefits of the tech hub plan, and why it has advantages over a cultural or tourism offering.

No-one responded to the generic info email address at Recreate Shandon, so I phoned Seán O’Sullivan to ask him to talk me through the Shandon plans.

But on our first call, he told me that there was no-one available from Recreate Shandon CLG to speak to the press and that he wasn’t willing to be interviewed and that he had an arrangement with Cork City Council that they would handle any press for the application.

I thought this would be highly irregular given that Cork City Council still ostensibly has to act as the local authority and deliberate on the planning application.

I checked with Cork City Council who told me Recreate Shandon “most certainly should talk to the press themselves.” When I contacted Mr O’Sullivan again he was away; he asked if he could respond to my questions by email. He has not done so.

Shandon Area Redevelopment Association (SARA) is an active community group who have come out in favour of the tech hub plans. There’s some crossover between the members of SARA and the board of Recreate Shandon.

Local butcher James Nolan is listed in Recreate Shandon’s companies registration information and is also a member of SARA. I stopped by his Shandon St shop, but he didn’t want to talk, apart from to say the plans were in the early stages and that Recreate Shandon has the full backing of SARA for their plans.

But not everyone in the area is happy. Some have highlighted the lack of transparency around how the tech hub plan was selected. One area resident showed me a part of their submission letter to Cork City Council:

The bottom line

Paul Moynihan is the Director of Corporate Affairs and International Relations with Cork City Council and he’s been involved with the deliberations around the Butter Exchange for years.

The main criterion that got Shandon Exchange over the line was that it was “identified as having a funding stream,” he tells me.

“There would have been a number of expressions of interest over the years: certainly we would have had some from the arts sector, some from commercial and entertainment, and some tourism proposals as well.”

“But realistically, a number of the projects that came our way didn’t have funding streams available. A multi-million euro development would require funding in some form.”

“There was no conclusion to proposals that didn’t have a funding stream because the council wasn’t in a position to put up the three or four million necessary for any given project.”

I ask him why some organisations weren’t formally notified that their proposals hadn’t been accepted. “Maybe there was a misunderstanding,” he says. “But any project that came to us, if it didn’t have an identified viable funding stream, it couldn’t been progressed.”

It’s not possible to see this viable funding stream at present but perhaps Mr O’Sullivan could have enlightened me; all talk has been of applications for government funding and for seeking private backers.

Butter trade, tech trade

To Mr Moynihan, the building having business uses is perfectly aligned with its history as a centre of trade and goes a long way towards attracting international investments for the project.

“There’s been an engagement with interests in the US,” he says. “We were aware of the history of trading and if a form of 21st century trading is to find a home there, we’d be trying to use the history and heritage of the building to create business connectivity and support for it.”

“Creating business connection and support both nationally and internationally, that will be part of the longterm viability of the project anyway.”

I ask him why Cork City Council saw fit to dispose of the building for a euro a year.

“That goes towards viability,” he says. “If you were to burden the development with substantial overheads that would affect the longterm viability of it. And the site value can be taken as a contribution towards the overall development plans.”

So the site value offsets the cost of Recreate Shandon CLG taking on the task of substantial upgrades and restoration of a council-owned building.

When it comes to business use not being as appealing for visitors, not keeping the building as a fully open and accessible public amenity - although there’s been some talk of community use for meetings etc, and the Dragon of Shandon festival have been reassured that their beastie still has his annual home - and no longer making reference to the new vision of the city centre’s use as outlined by KPMG, Mr Moynihan is a pragmatist; the building needs repairs, and it needs a financially solid plan to achieve this.

“The proposal that’s there also has roots in the local community, through representation on the board and consultation with the local community,” he says.

Heaven rest us, there is asbestos

€3-€4 million to renovate the building is a far cry from Camden Palace’s €40,000.

But the mechanical and electrical fit-out alone for Recreate Shandon’s plans comes to €635,000, according to documents lodged with the planning application.

And there’s the little matter of an asbestos roof on the 1984 part of the building, which, while currently stable, would be removed as part of the overhaul. Asbestos removal is expensive so maybe Mr Moynihan’s estimation of three to four million is realistic.

Sample

Former Sample Studios director Aideen Quirke tells me she recalls their proposed figure for restoring the building was €250,000.

Current Sample Studios director Aoibhie McCarthy joined Sample Studios in 2020 and is currently working with Cork City Council to identify a new city location for the artists’ studios; she’s keen to promote a positive message about the studios’ engagement with city council.

“The application was made, and wasn’t successful and we’re since working with Cork City Council to find another location,” she tells me.

I need to make it clear, then, that Aideen Quirke no longer works with Sample Studios, although she was at the helm when they put together their proposal for the Butter Exchange. She says it was a “robust and ambitious” proposal. It was made around the same time the Camden Palace made theirs.

“Dream venue”

“Sample Studios were in the Tax Office and we always knew we’d have to leave, so we were always looking for a more permanent base and the Butter Exchange was our dream venue,” she tells me.

“I could just see it being used as a cultural space. A lot of artists would have seen it as a natural space for art studios. We had a need, and the building was there, so we contacted the city council about putting together a proposal and they told us there were a few things we needed to do.”

Sample Studios conducted a feasibility study, worked with a heritage architect, and put together lists of potential funders including the Heritage Council, “very similar to the funding the tech hub seems to have identified, so we’d scoped all of that out.”

As an organisation that had been a limited company for almost ten years, they were also eligible for a loan, and had plans for how to monetise some of their art output to repay this.

But Aideen says she thinks the council and the local community’s receptiveness to arts use was soured by the failure of the craft centre, which left the impression that no arts business could work there.

“I think that undermined the understanding of how creative and cultural business works,” she says. “Sample Studios took a long time to be taken seriously as a self-sustaining business model that supports cultural activity in Cork.”

Aideen says she doesn’t know what criteria were used to decide that Sample Studios’ proposal was not viable. “We were never given any false hope or guarantee,” she says. “All we did was get it to the stage that it would have been considered, that it would have landed on someone’s desk.”

“I believe the CEO was aware of our aims and we had support from the arts office although this was outside the city plan at the time. It was very tentative and loose and we never thought it was a definite. There wasn’t any elected representative or council executive on board: it was just to bring it to their attention. I don’t even know how far our proposal progressed, if the city architect reviewed it or anything.”

While Aideen believes the most important thing at present is for the Butter Exchange building to be brought back into use and to be protected, she doesn’t understand the rationale behind putting co-working spaces and the kind of innovation hub that could easily be located in any of the city’s peripheral business parks in one of the city’s most important historical buildings.

“What’s the point of having it in a historical building in the city centre?” she asks. “In what context does it support business or technology?”

“In terms of infrastructure and in terms of the use of the building it doesn’t seem to make a huge amount of sense. There are already co-working spaces in the city; are they in full use, has that been scoped out? It feels like some buzz words have been used but that the plan is very vague. I don’t know how it’s going to be a self-sustaining model, or in what capacity it will be supporting businesses.”

In the meantime, there’s that draft City Centre Revitalisation Plan, in which a large accountancy firm has formalised and acknowledged development strategies that artists have been talking about in the city for over a decade. To not have had them acknowledged earlier has led to a missed opportunity, Aideen tells me.

“People are leaving Cork because there’s nowhere to work, not enough venues, not enough spaces to exhibit. That’s the missed opportunity.”

“But there have been other missed opportunities, and it’s led to the current situation, where there are all these crumbling buildings that should be being activated by culture and art.”