Feeding Cork: inside the city's only food bank

Feed Cork is catering to rapidly growing numbers of people but manages to offer a stigma-free, service-with-a-smile way to help feed over 200 struggling people per week.

Hamp Sirmans and Sharon Mullins are sitting in what looks like, at first glance, a trendy down-town café. It’s newly renovated, with wrinkly tin on one wall and tasteful lighting.

But when you look around them, you notice that the family sitting behind them are Ukrainian, with three small, energetic boys charging around while the parents, unspeaking, look around anxiously.

There’s also a near-constant bleep: it’s the sound of an automated queue-handling machine, its digital face reading 67, 68, 69 as the tickets are called.

Wednesday and Thursday mornings, this building opens its doors as Cork city’s only food bank, Feed Cork.

Founded in the Born Again Christian Cork Church on Oliver Plunkett St Lower in 2017, Feed Cork’s growth is, of course, hardly cause for celebration, because of the growing number of people that need to avail of their services.

When the service started, they only opened one morning per week. Now it’s two.

As we reported this week, 2022 will see almost double the number of new registrations for the city service as 2021 had: 917 new people have registered via an anonymised app the charity uses to monitor their numbers so far this year, with the two toughest months yet to come and with fuel costs adding to the crunch for many families in the winter months.

There are 1,843 people registered in Cork city via the app; Feed Cork also has a centre in Drimoleague serving West Cork. Some come every week, while some will come fortnightly or monthly. Volunteer Co-Ordinator Sharon Mullins estimates that they are helping over 200 families per week.

Sometimes, in a dream scenario, people stop coming at all. People’s lives move on: they find work, pay off debt, leave addiction or abusive relationships, begin to manage a mental health condition. They stop needing the service.

“We have people that have come through here that have gone back to education,” Sharon tells me. “We get such a mix in here. It’s a great community. Some of our volunteers are even people who would’ve been clients and I just think that’s amazing.”

Hamp, a Pastor of Cork Church and a founder of Feed Cork, talks me through what happens when you visit Feed Cork: you come in, you get a ticket, and then you have coffee in the friendly, bustling café space while you wait your turn.

When you’re called, you go through to the food hall, where crates of staples, dried goods and chilled and frozen items are laid out, with volunteers on hand to help.

On average, a Feed Cork client will collect between €100 and €140 worth of food in their visit. But most clients are feeding a family with that.

Before Covid, the food was distributed rigidly in the form of a collected pre-packed basket, but now, clients choose their own foods: this can save waste, but it also has another big advantage: it makes a visit feel more like a supermarket trip.

In fact, the entire experience is painstakingly designed to minimise the sense that clients are using a charity.

“We thought a lot: How can we do this in a way where we restore dignity?” Hamp says. “And a lot of the kids that come in don’t even know that this is a food bank. They just think, ‘oh, we’re going to the café and the food hall before we go home.’ We try to do it that way.”

After School Fuel

Last Spring, Feed Cork started another outreach project which sees volunteers delivering meals to children who don’t have enough to eat on weekends.

The charity works with Liaison Officers in schools on the DEIS (Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools) programme to identify children who need additional support and who may be going hungry for a variety of reasons. Hunger then becomes a major risk factor for not completing school.

Catering company Brook Foods donate pre-portioned meals for the 50 children from 13 families, aged right the way from Junior Infants up to Senior Cycle, that are currently signed up to After School Fuel, which positions itself as a health and nutrition scheme but which is arguably quite a lot more.

“So the idea is first of all that the food is nutritious, and secondly that the kids will be able to heat it up themselves,” Hamp says. “We have things like Thai Curry: a variety of options. We went to a school and pulled in the kids from third class and got them to do a taste testing of them, which was fun and it helped us shape a menu that is kid-friendly.”

This scheme is likely to grow in the coming years. ”We need another van,” Hamp says. “The idea is that we get our own kitchen and start making the meals ourselves, but we’re a couple of years away from that.”

The stories he shares are difficult to even hear: a mother of five, two of whose children are autistic, had a double mastectomy following a breast cancer diagnosis, and just stopped being able to cope. “We sent up a volunteer to help get the kids out to school and two of the children, a brother and sister, were sharing a winter coat,” Hamp says.

“We go to houses where there would be windows broken out, where there are experiences of violence and trauma.”

It’s called After School Fuel, but this scheme runs for 52 weeks of the year.

Feed Cork shifts somewhere between six and seven tonnes of food every fortnight. I paid a visit to FoodCloud’s Little Island depot in 2018 for an article for The Echo: the food waste charity counts Feed Cork as its biggest client.

“We also collect food that’s approaching its best before date from shops, so we have a refrigerated truck going around a couple of nights a week,” Hamp says. “We can freeze things down and redistribute it.”

“We have credits allotted from an EU programme through the Department of Social Protection and a list of 25 items we can purchase with those: cereals, teas, coffees, sugar, tinned foods, pastas and pasta sauces.”

Feed Cork is, of course, housed in a church: Hamp is a Pastor with Cork Church who arrived in Ireland 11 years ago.

“At that time, my background was in Biblical education and they were building a training centre here, but I had opened a food bank in Greenville County in South Carolina in 2008, when the economy went into downturn. Food poverty was at 20% and there was no government help.”

Greenville County has a population of 1 million. “This was physical poverty,” Hamp says. “The people we were dealing with were at the end of their tether.”

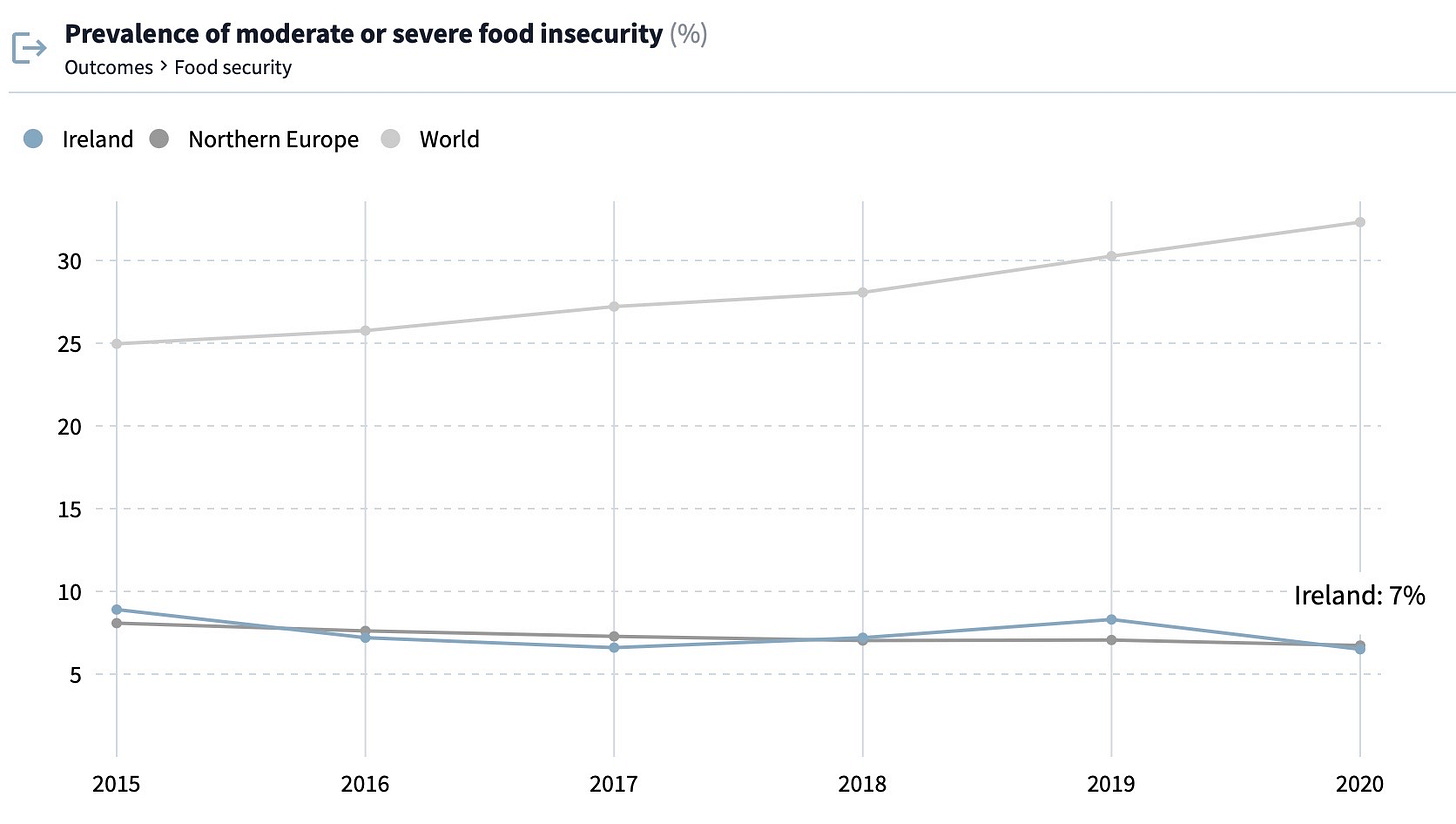

In Ireland, where “moderate or severe” food insecurity is at about 7% but where malnourishment is rare, we have comparatively good social support structures, Hamp says. Compared to the US.

“We’ve watched one of our clients recently going from living in substandard social housing into a brand new house set up just for her and her family. That was a woman who had been through abuse and everything else. That would never happen in the States.”

But the situation is worsening: everyone I talk to at Feed Cork can feel the increase in numbers, can see that the makeup of their client base is changing.

There are Ukrainian people coming in. In fact, there are now some Ukrainian volunteers, including renewable energy engineer Gennadiy Tupin, who arrived with his wife from Odessa in March having witnessed missile launches. He can act as translator for those Ukrainians who have little English.

But more noticeable are the working people: before, pretty nearly all clients were facing mental health or addiction issues, but now, the cost of living crisis is pushing more and more people in work to use their services, and students too.

“That type of client has picked up with the cost of living and inflation happening,” Hamp says. “One of our goals is to prevent homelessness, to free up money so that people can stay in their homes. Because the number of people who are choosing to pay their rent over food is increasing.”

Any such thing as a free lunch?

Although Hamp says his drive towards charity is deeply integrated with his faith, he is adamant that there are no spiritual strings attached to the food donations Feed Cork distribute.

“Yeah, when Sharon first came in to work with us nearly five years ago, she thought we were bible bashers,” he says with a wry grin.

“We have volunteers here who sit and chat with people, and they might offer prayer, but this is by no means a gotcha moment,” he says. “People are vulnerable when they come here. We talk to them, but often it’s about family and stuff like that.”

Hamp brings me for a tour of the food hall. It is agreed that I am not going to try to interview any clients on my visit: they have - no pun intended - enough on their plates without answering prying questions during their visit to Feed Cork.

But I can talk to the volunteers.

The charity operates around a core of about seven or eight key people, and then a wider pool of about 35 volunteers.

Walking around the food hall, what’s remarkable is that almost all of the volunteers have faced hardships in their own lives. Several, including Pat Galvin, the longest-serving volunteer, are widows who feared isolation after the deaths of their husbands. “There’s a great sense of happiness here,” Pat says. “Our customers are lovely and they appreciate everything we do.”

Working alongside her on the chilled and frozen area, where stacks of Marks and Spencer ready meals are joined by mini bottles of Innocent orange juices and a crate of red peppers, is Davina Staunton.

Davina started coming in as a Feed Cork client, she tells me: she was being floored by twin burdens of debt and depression. Now, she volunteers.

“After about two or three months I started coming in volunteering and it’s the best thing I ever did,” Davina says. “You forget about your own problems. I’ve met fabulous people over the years. They’ve been very, very good to me.”

Liam Fitzgerald found himself with time on his hands having stepped back from work to care for his wife, who was ill, and their autistic son. He’s become a real backbone of the Feed Cork operation, one of few who kept the service going right the way through Covid.

“We were trying to look after the logistics of getting food out to people and we even did a drive-through for people to collect." he says. “It was madness, but it kept me sane because I had something to do and somewhere to go. I was even allowed go beyond the 2km because I was providing food to people.”

Liam thinks that facing your own challenges in life might make you more empathetic, more able to see the plight others are facing. Not that he’s holier-than-thou about it: I asked him. Because it can’t be easy, looking after his wife and son. He shrugs it off. Positivity is the key, most especially so when you are dealing with people who could be in the eye of any one of a number of horrendous storms.

Sometimes, he says, clients need more than just food when they come in.

“The clients want to share their experiences and traumas and you have to take that on board, but you want to keep a positive outlook,” he says.

“You could ask them the most casual question and somebody could outpour a lot of stuff. And I might be the only person they will speak to that week, and I’m aware of that. It opens your eyes to the fact that there are a lot of people in the world suffering more than you are.”

Liam, too, has noticed the changing demographic this year. “Oh, yes,” he says, nodding. “There are clients that are absolutely pinned to their collars with rent or mortgages and there’s just not anything left over to feed their families.”

If almost all of the volunteers have faced their own struggles that have led them to this point, what about Pastor Hamp? He grew up in Florida. I ask him if he was always religious, if he was brought up in a Born Again family.

He laughs heartily. “Oh, no. Definitely not. I grew up in a very chaotic, wild situation: that’s a whole other story, but I grew up with a lot of trauma. Gun violence, drugs and addiction, that sort of thing. And poverty.”

He recalls going to school with the same clothes on for weeks on end, and queueing for his lunch with a cruelly conspicuous bright orange lunch ticket.

“The free lunch tickets were orange, so I’d have to queue up with an orange ticket and the other kids would pick on me for it,” he says, shaking his head at the memory.

“So I know what it is to come from that. And I think that’s probably why doing this is such a big thing to me, because I identify so much with those kids.”