Dreaming big on the Basic Income for the Arts

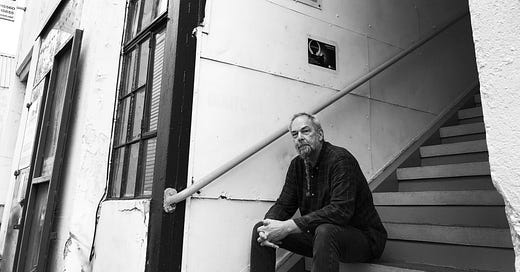

Serge Vanden Berghe is one of 212 artists in County Cork to have been awarded the new Basic Income for the Arts; he tells Tripe + Drisheen what the three-year pilot means for him and his art.

Not quite winning the Lotto, maybe, but when artist Serge Vanden Berghe opened his email whilst working in his studio in Outlaw Studios in early September, he let out a whoop of joy.

“Another artist was in the back working and I got the email and went, ‘YAAAY!’ and ran through and said, ‘I got it!’ and he said, ‘I didn’t.’”

What Serge had received was news that he had been selected for the Basic Income for Arts (BIA), under which 2,000 artists and arts workers in Ireland - 212 in County Cork - have been chosen to receive €325 per week for three years as part of a pilot scheme.

The BIA scheme is intended to serve as a study as well as providing some post-Covid relief for a sector that was hit hard by almost two years of closed galleries, theatres and venues. The scheme, based to an extent on Universal Basic Income models, was introduced by Arts Minister Catherine Martin; it’s not means-tested and there’s no proof of merit required. No-one judges your work: you applied and if you were eligible, your name went into a hat and 2,000 artists were selected, while 6,000 artists were not.

Serge and one other of Outlaw Studios’ 13 resident artists were granted a place on the scheme.

The first payments were made in late October, so Serge hasn’t had time to truly assess how much of an impact it’s going to have on his life and his art.

“I have to do a survey every six months, and it’s started, so we’ve done the first survey,” Serge tells me. “There are questions about income, but there are also questions about mental health and physical health. That process of a twice a year survey will be fascinating, I think.”

But Serge knows this is a game-changer. For years, he has combined part-time casual work, mostly for theatrical and TV set design company Triangle Productions and before that for Dowtcha Puppets, the street theatre and puppetry company, with his own art practice.

Now, he won’t have to take jobs he doesn’t want to do to make ends meet, he says.

“I can organise myself more professionally. I don’t have to go back to paid work every six weeks, because it’s been like that for so long: up and down, up and down. Often I’d just be getting into my process and I’d have to leave to go and work for a few weeks. Then when you come back to the studio, you have to get back into it again. You lose a lot of time. Now I can keep going.”

“The biggest thing, though, is that I have much more self-confidence. In my work as well myself: I can be bolder too, because in the back of my mind, I’ve always had that I have to make things to sell. I feel more free.”

Serge le Belge

Things could have worked out very differently.

Serge is originally from Belgium, and moved to Cork with his wife Veronica in 1992. Serge was a craftsperson and a stay-at-home parent to the couple’s two sons.

“I really enjoyed to be a foreigner here in those early years,” he says. “Irish people are very welcoming, into families and other circumstances, but as a newcomer you don’t know the etiquette. As a foreigner, people forgive your mistakes so I could behave more freely here than I could in my own community in Belgium where I was expected to know the rules.”

Now that their children are adults of 28 and 26, before Covid, Serge had been having his doubts about whether he was actually going to continue living in Ireland at all: in 2019, he spent eight weeks in Belgium. “I was trying to decide if I was going to retire there,” he says.

“But when I go back to Belgium, I go back to a museum, to memories. It’s a different country. It has changed in those 30 years and it’s not the same country I left. I won’t call it home anymore, except when I’m in the forest or the wild.”

While back in Belgium, though, Serge stumbled upon an artwork that has inspired his current solo exhibition, Sacred Earth and Other Stories: a 14th century altar piece by Ardennes sculptor le Maître de Waha.

Reliquaries and the sacred

During the Covid lockdowns, Serge began to make his own versions of tabernacles and religious reliquaries. Made from everyday materials like recycled cardboard tubing, polystyrene and wood and with small doors that require the viewer to open them and peer inside, they don’t contain saints and religious iconography but rather Serge’s own take on the sacred.

“In our society, nothing is sacred except money and I think we need to find our sacredness again,” he says.

One lit piece dominates the centre of the room: inside, some pieces of wood and seaweed.

“In Castlecove in Kerry, there’s an ancient forest, and the sand covering it disappeared in the 1930s,” Serge explains. “About 40 stumps appeared, and they are 4,000 years old. That’s my relic. It’s a bit of bog wood, not a saint’s finger.”

“I’m an agnostic, but I love the Early Middle Ages: it’s a period that is fascinating and the only artistic expression at that time was through the religious. I would like to keep that iconography, with a different content. It’s a period where there were no states in Europe, just small communities trying to organise themselves. It was a time of enormous novelty, in thought and in technology.”

An outlaw and an anarchist

If the idea of a Europe without states is appealing to Serge, it is because he has been an anarchist since he was in his twenties and working for the peace movement in Brussels.

Rather than the tabloid misuse of the word anarchy to describe scenes of violent disorder, anarchism is a philosophy based on peaceful, non-violent actions, Serge is keen to stress.

“In practical terms, it’s about avoiding like the plague any power position,” he says. “You spread the power, give a voice to everyone, respect everyone no matter their circumstances.”

“When I was in the peace movement, I was working for an anarchist organisation and really there were collective anarchists and individual anarchists who live their anarchy in their own lives. I have moved more towards the individual; my political activism now is personal.”

“So I try to find ways to have collective decisions when there are other people involved in my life. It’s not easy. Even in a group studio like this,” he says, gesturing around at the Outlaw Studio space, “even if it’s not said or seen, independent artists’ groups are usually trying to follow that philosophy. It’s not democracy; if someone isn’t happy, we try to sort it out. But it takes time. We talk.”

Serge is most happy exhibiting his art outside of formal gallery spaces.

For the past month, and for one more weekend, Sacred Earth and Other Stories has been on display in Outlaw Studios, the studio space founded in a part of the former Ford Factory in the Marina Business Park in 2005.

Serge, along with painters John Adams and Suzy O’Mullane, was one of the first artists to have a studio there, while most of the building was full to the ceiling with a pile of builder’s rubble that Dowtcha Puppets and Outlaw Studios co-founder Cliff Dolliver emptied by hand.

Serge had met Cliff through working on a Community Employment (CE) scheme; at the time, this was one of the few ways to pick up a basic income in the arts. Unlike the BIA pilot scheme, which is not means tested, and not linked to output or hours worked, CE is a system riddled with hoops to jump through.

“To get the CE scheme I had to be on the dole, so first I had to have a PAYE job for a year,” Serge says. “I was a cabinet-maker’s apprentice for one year and then I went on the dole for another, and then I could apply for the CE scheme.”

Serge first worked with theatre company Corcadorca, who were staging their critically acclaimed production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in Fitzgerald’s Park at the time. Cliff Dolliver was the designer.

“I went from Corcadorca to Cork Community Art Link, and then into Dowtcha Puppets, and puppetry and parades,” Serge says. “It was a three-year process, but it was more useful than a degree.”

Ford

Serge has a special relationship with the old Ford Factory where he has been based for so long: normally only let for industrial uses, Outlaw Studios were the first to utilise the relatively low rents and adaptable warehouse spaces for creative purposes. Now there’s Rebel Reads bookstore, an evangelical church, a paintball range and more.

“I love it,” he says. “It’s a beautiful building and significant in the history of agriculture in Europe. Now it’s being renovated, painted and used for lots of different uses, but when we were first here it was really outside the leisure uses of the city.”

The nearby Marina Market, plus the amenities of Atlantic Pond and Marina Park mean that the area in now in transition from being an industrial location to being “the centre of the leisure side of Cork,” Serge believes.

But he hopes it will serve the artistic community too: while galleries and heritage sites can serve as exhibition and performance spaces, he stresses that artists need practical, adaptable, large spaces too, ones that can be modified at will, or used for storage. He thinks the former Ford buildings should serve as a creative hub into the future of the Docklands Development.

“This Ford Factory has working spaces of all sizes,” he says. ‘The artistic community needs a space like that. If you could have a site for that here, with working spaces, things like storage space for sets, I think that would be great.”

He’d also like to see more exhibitions happening at Outlaw Studios: before, it would open to the public for Culture Night annually, but not really for other things. The security of the €325 per week for three years the BIA will bring is helping Serge to envision and plan for a more secure future.

He’s even invested in a set of gallery lights for Outlaw Studios; he’s using them for his own exhibition but they will also be available for other artists who wish to exhibit in the space in future.

“The BIA is three years, so I can make plans, I can invest,” he says. “But it takes a while to take it all in, because it’s significant.”

Sacred Earth and Other Stories is open for three more days, from 10am to 5pm on Friday, November 18 until Sunday, November 20 at Outlaw Studios, Marina Commercial Park, Cork City. More info here.