Chippy Loves Ya Cork

But does Cork love the tireless tagger back? Tripe + Drisheen goes on a walkabout with Chippy, one of Cork's busiest graffiti artists.

If you’ve ever looked up while walking around the streets of Cork city, you’ve more than likely seen the name "Chippy." Almost always in bright orange, "Chippy" is the tag belonging to a twenty-one-year-old from Mayfield who's one of the most prolific taggers in the city. Chippy is his old Xbox gamertag.

Chippy has tagged some of Cork's most notable buildings and structures, including Roches Stores and the Shakey Bridge, as well as quite a few derelict buildings. Some of his tags are so high up, you wonder how the hell he got up there.

Chippy is quiet and unassuming, and on the night we meet as the Midsummer Festival plays out in the city, it takes a few minutes to break the ice. He's dressed in an orange jumpsuit, and a large stain on the right arm of his jumpsuit is the only thing that suggests he's a tagger. Quickly enough after meeting, he shows me one of his tags as we're walking down Merchant's Quay and explains the process of painting it.

"It’s way in the far back, there," pointing under the Mary Elmes pedestrian bridge which crosses over the River Lee at Merchant's Quay.

"I had to drop under the bridge for that one. You can only get three fingers into the holes under there, so I was holding on with three fingers all the time." He lets out a little chuckle every time he finishes a sentence.

Then he points across the river to the warehouse on Brian Boru Street, showing me one of the biggest tags I've ever seen. "You can see the Y, see the blue bit there," he says. "I spent a good half hour at least, with a bucket of paint and a paintbrush; I ran out of paint at the end."

I’m flabbergasted, wondering how I had never noticed it before. The letters are easily 10 feet or more. Once again, it spells out CHIPPY.

A natural born climber

Chippy has been tagging for the past two and a bit years. But tagging comes secondary to his love of climbing. He began climbing buildings as a teenager, scaling rooftops to hang out.

“Ever since I was like 14, I was climbing up the side of buildings and getting on roofs,” he says, “I wasn’t tagging or painting or anything, I was climbing up there to hang out, listen to music, look at the view or whatever. But I think when I turned 18, I thought, maybe I should tag so people know I got up on the roofs.”

Chippy says he doesn’t tag for any particular reason; he has no art beyond his name to promote, and he says he is definitely not a graffiti artist. He plays music, but his tags aren’t to promote that. He doesn’t have a job. “I just kinda do a lot of random stuff,” he says, “like every day there’s a new thing to do.”

Orange is his colour, a very specific orange. “There’s a shade of orange that I use, and if I can’t find that shade of orange, I usually just won't get an orange unless it’s that specific one,” he says, and it’s rare for him to vary from this.

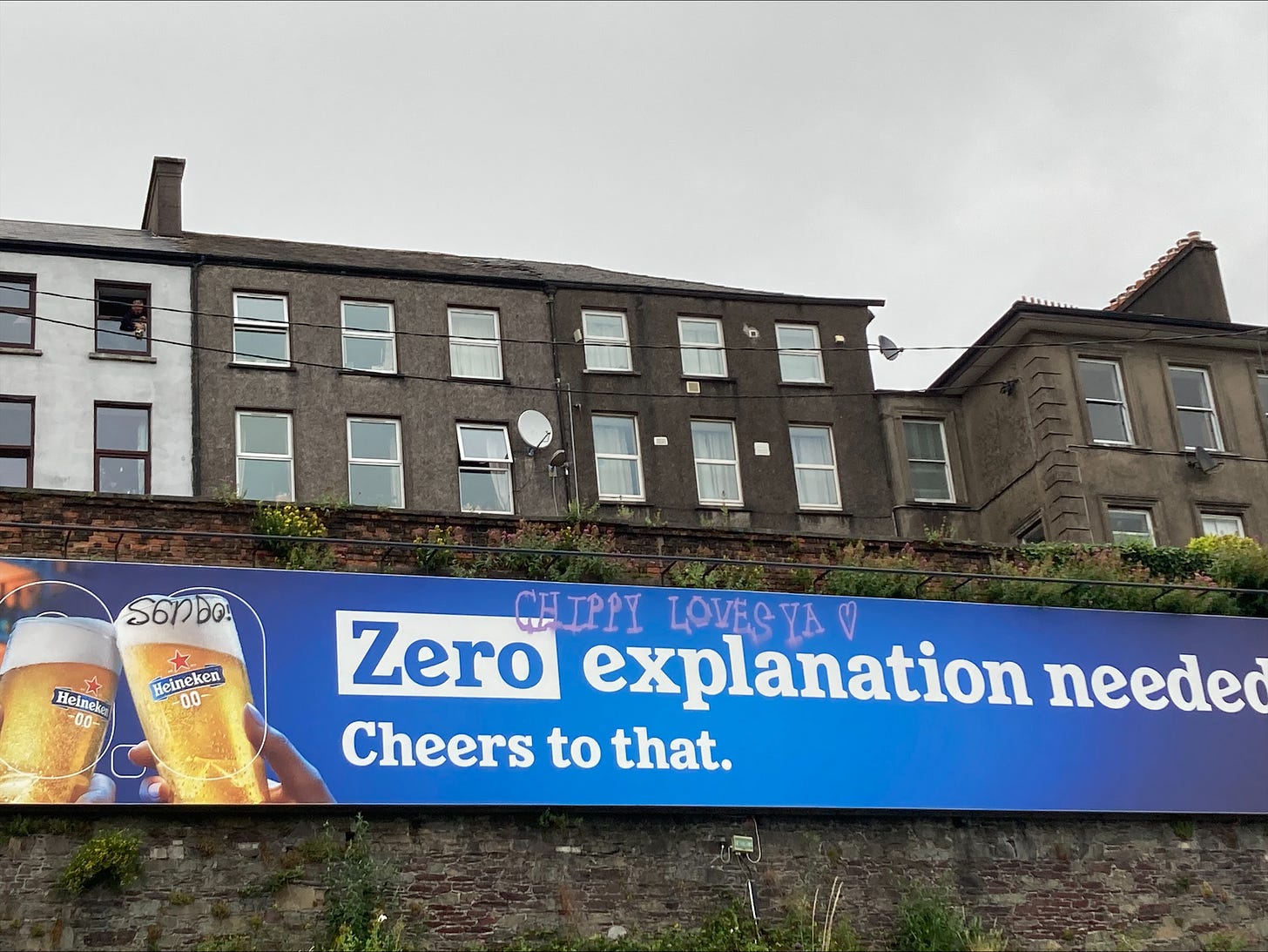

We make our way towards the train station on the Lower Glanmire Road, where he has one of his most visible tags. “Over here, up the hill, is one of my most famous ones, ‘Chippy Loves Ya,’ on the billboard,” he says. “I have that one there because my girlfriend lives here, so she passes it all the time.” Unlike his other tags, it’s in lilac, a color he tried out for a little while. He says it reminds him of his girlfriend.

The Chippy Loves Ya tag is dangerously high up, and it isn’t the only one on the wall. Chippy points out three other tags while explaining the process of getting up there. “You need to go up the steps, and you can hop over the wall,” he says, pointing up at the bridge. “You see over there on the wall itself, I got over there too. I used the bolts; you can grab onto the bolts. It’s just such a nice place, you know what I mean? There are so many rocks, and it’s so layered.

“An eejit and shit”

I ask him if he enjoys the adrenaline rush related to climbing buildings or scaling escarpments like those around the train station. "Somewhat, I feel like I don’t do it entirely for that, but it definitely is an aspect," he says. "When you're on the side of a building, you’re not really thinking of much else; you’re hanging off the side of a building."

From there, we go to the place where it all began for Chippy’s tags: lower Oliver Plunkett Street, the quieter end of the long pedestrianised street that connects Grand Parade to Parnell Place. He points out four tags and shows me his first piece ever.

“I wrote 'Chip'; I was really paranoid because it was one of my first times I was out tagging, and I thought I heard someone, so I left,” he says. “But someone mentioned it to me one day, they were like 'Hey, I saw Chip written. Did you get scared and run away?' and I was like, 'That’s exactly what happened.' So I came back and finished it, two years later.”

Chippy says he has no influences; he was never really interested in tagging culture. He just wanted to prove how high he could climb to the world around him. In the small area between and around the train station and bus station, he has at least twenty tags, including "Chippy Loves Ya" by the train station. He’s definitely left his mark.

He only carries spray paint with him when he goes out with the intention of tagging. Otherwise, he carries emergency paint. He doesn't exclusively tag at night either. His most controversial tag, on Roches Stores, was painted during the day while he was hanging out up there. It, and many of his other tags, received a lot of criticism on a Reddit Cork thread. The poster went straight to the heart of the matter asking: Who is ‘Chippy’ and why??? (They also called him a gobshite and a commenter called his tagging “littering with paint”.)

“It makes me feel proud in a way that people have noticed, you know what I mean, that it caused that much attention. There’s a lot of graffiti artists who are much better than me, you know what I mean, and they just don’t get recognition, and I just put shitty tags up,” he says.

“And then obviously, people calling me an eejit and shit, it's obviously going to happen, you know. That’s the whole point of graffiti. If people liked it, no one would do it. It's fair enough, like, my tags aren’t good. I fully understand that they look awful, I never denied that, but I’m doing it for myself, not doing it for other people.” At times, Chippy seems not grasp that by its nature grafitti is for everyone, even if a large or little percentage of everyone doesn’t want it.

Despite the online criticism, which he understands, he thinks others are supportive of what he does.

“As long as there’s a good balance between people who are complaining and people who like it, like you can complain about it all you want, there are tags in the city I don't like, and I complain about them, so everyone has a right to complain,” he says. “But they shouldn’t complain about me as a person; they should complain about my art.”

I asked him whether he thinks about the heritage of a building before he sprays. “Yeah, I’m always thinking about that,” he says.

Chippy’s code

“But for the Roches Stores dome, it’s a bit of copper, you know what I mean? It’s not even spray paint; it’s wall paint that will wash off so easily. When I was up there, there were people’s names etched in, not with paint but with knives or whatever, they go all the way back to the 80s. So, I was looking at that, and it was like all these people had been tagging their names since the 80s, and you don’t even see it, you know. But theirs is permanently in, mine can be washed off.”

Another tag I ask him about is on the side of Electric on Grand Parade, where he painted near a piece of commissioned artwork. “I’d never paint right next to it, I feel like I left enough space for that one,” he says. “It’s not even a whole wall of artwork; the tag and the artwork are somewhere else.”

Despite this, Chippy says he has a code; he would never tag an active small business or somebody’s house. “If it’s a big corporation, they can afford it; it's nothing to them to pay a couple of hundred. But if I paint on a small business, that actually affects them, so I wouldn’t do that.”

Nor would he tag old heritage structures, he claims, despite tagging Roches Stores and the Shakey Bridge. “The art gallery on Grand Parade, a day ago, two days ago, a guy named Evoke, he tagged it, but I’ve been up there ten times and I never painted it,” he says.

“I’d never paint a school, and that’s a school building, and it’s so pristine and white as well. My tag would just look bad up there, and that would ruin it, you know?”

That said, he does have one tag he regrets, where he tagged a house without realizing it. “I didn’t realize it was a house because it looked like a temporary wooden board, so I painted on that,” he says.

He found out a few weeks after that it was a garage door and says he regretted it since.

"If I could take that back, I would."

Chippy doesn't think he hurts anyone with his tags, and he mostly paints on derelict buildings. In his mind, the buildings are neglected and need to be repaired anyway, so what harm is he doing by painting on them?

“There are a lot of buildings like that; morally, there’s nothing wrong with painting on something like that,” he says. “They’ve been abandoned for years, and you need to repaint them anyways because the paint is coming off. So there’s actually zero harm in painting it.”

In many cities around the world, graffiti and street art are a staple of the urban fabric, and Chippy finds that what he does is not necessarily unique. “If you look at every city in the world, there’s graffiti absolutely everywhere. No building is safe; if you go to Berlin, if you go to London, they’re covered, head to toe,” he says.

“I feel like Cork itself is such a small city, a lot of people notice it. If I went to London, and if I was painting exactly like I am now, I would go completely under the radar.”

We continue our walk down Oliver Plunkett Street, where he takes me to another collection of tags he painted on the top of Roches Stores, alongside a piece of art painted with his friend Nestor. This piece is impressive; Nestor’s three genies watch over Caroline Street, adding character to an already colorful part of town, surrounded by commissioned art.

Chippy doesn’t see the difference between graffiti and commissioned art, but he thinks that graffiti can have a stronger message. “No one is actually asking for it, it just appears. And, a lot of the time, commissioned art has no style; it’s controlled by the business. They don’t want anything offensive.”

He also doesn’t see the difference between graffiti and advertising. “It’s just that advertising has been so normalized that no one actually cares, but in a way it's more harmful,” he says, “They’re getting people to spend money; you could actually get somewhere with an advertisement. With a tag, it’s not harming anyone. Nobody’s tag has ever harmed anyone. Advertisements make the place look ugly.”

On street performers, Banksy and toast

We pass a street performer on Oliver Plunkett Street, which prompts another opinion on public space and art. “If you think about it, isn’t street performance kind of like tagging as well? Where it’s like media that you never ask for it, it’s there,” he says.

“But it takes up space, and it's loud. If you think about it, if there’s a really loud street performer, you mightn’t want to go near there, and then you won’t go to businesses near there, but if there’s paint on a building you’re not going to stop going to that building.”

We return to St. Patrick Street, where he shows me a few more of his tags. These ones are his most recent. One sits on the old Clarks Shoes shop, now derelict, and another in the alley by Penneys says “Chippy La La Loves You,” referencing a Pixies song. There is one, however, that he does find unappealing, even though it doesn’t exactly break his code, in his mind.

“That one’s kind of unappealing to me honestly,” he says, “I don’t think it does (break my code) but it feels like it does. Even to me, it feels like it does, but it is French Connection, so it's not against my principles.” I ask if he’s not damaging old brickwork. “Well, you can remove graffiti from bricks.”

From there, we go over to have a look at Roches Stores. He shows me how he got up and shows me two more tags he has on the buildings beside it. I ask him about how he feels about painting on a building that’s almost 100 years old. “But that’s not that old, there are people who are that old,” he says, “But like, what if in 100 years graffiti becomes a part of our heritage? That happens, like New York graffiti.”

“Even Banksy, when Banksy paints on a building, they don’t even consider it ruining a building. It doesn’t make sense.”

He continues with more equivalents, “this is a bit far out, but a caveman, painting on caves, imagine if that was just a natural cave, back then you could have been like ‘why are you painting on nature’?” he says, “Imagine I tagged a cave right now, that’d be considered really bad. But they did it all those years ago, it might have been considered bad back then. Now we look at it as part of our history, we’re glad that they did it.”

Chippy has been on the roof of Roches Stores many more times than the time he tagged, just hanging out. He even brought a toaster up once. He points up at a window, “That’s where I had my toast, in one of the windows to the left,” he says.

“Inside one of the windows, there’s a socket, so I got an extension cord and I plugged it in.” The window was already open. “I brought a girl on a date up to Roches Stores, and ate toast,” he says. I ask if he got a second date. “Yeah, we’re dating now, she’s my girlfriend. The toast worked.”

There has been word on the street that he’s being searched for by the gardaí, and he hasn’t been out as much as usual. “I heard about it through another graffiti guy, he heard them over, asking where I was,” he says, “Apparently they were down here, and they were pointing up asking random people. They went to the skate park, I think and started asking a bunch of people at the skate park who I was, I’m not even a skater.”

“I’ve toned down the graffiti a lot because they’re looking for me now. I’ve heard that they’re actually properly searching for me. I feel like if people actually care that much, they get pissed off about it, I’ll tone it down,” he says, “But Roches Stores is the only time I’ve really thought about it. Every other building people have actually really liked, even the billboard they really like. Most of them they really like.”

-Kilian McCann

Flower power

Chippy and Kilian had been on their tagging tour for about an hour before I showed up on St. Patrick’s Street, which is also the location where Chippy would love most of all to leave his mark. More about that in a minute.

I don’t know the first time I noticed Chippy: the city is full of shitty tags, and only a few interesting ones. It’s probably worth pointing out that there are category differences in graffiti: tagging might be the purest and most simple form. There’s also lettering, bombing, and pieces, short for big elaborate artworks, or masterpieces.

There’s plenty of each to be seen on the streets around the city, and every year the City Council spends considerable money bringing in big-name artists such as Aches and Cork native Conor Harrington, who have both painted substantial pieces in the city centre as part of the Ardú Street Art Festival. But away from the commissioned pieces, graffiti artists are regularly seen painting on Ferry Walk near the Mardyke and around the walls on the streets around St. Fin Barre’s Cathedral.

Taggers, however, go everywhere and anywhere, and nearly always cross lines.

The first time a Chippy tag stuck with me was when I was over on Lower Glanmire Road by Kent Station reporting on those steps leading to Horgan’s Quay, which BAM and Clarendon Properties refuse to open. Chippy had tagged the gate on Lower Glanmire Road which blocks the entrance to the stairs, and it was a nice big piece. More art than a tag.

For about a month, Kilian and I were talking about Chippy as well as tagging and an article that came out earlier this year in The Financial Times featuring the legendary tagger 10 Foot, who’s likely around twice Chippy’s age and has tagged in some of the most improbable locations across London. His tags are in Cork too. 10 foot refuses to sell out. Or to stop.

By contrast, it’s hard to ascertain what drives Chippy. When we meet, he hasn’t tagged for a few weeks, and you get the impression that when he does stop, it’ll be easy enough to quit.

Chippy wasn’t hard to find in real life, and he doesn't mind being photographed. His scrapes with the police have been few and far between, and his parents know what he does. He says his parents would prefer he stopped.

While we walk the city heading up to Blackpool and back again via Carroll’s Quay, we see about half a dozen more Chippy tags. As tours go, it’s pretty underwhelming: Cork doesn’t have skyscrapers or a bounty of rail bridges for Chippy to scale and leave his mark. Instead, he shows us spots near the Heineken Brewery where he’s reached the other side of the river to leave his tag. 10 foot it is not.

But, the tags were only part of the reason we showed up. It was more to get a sense of why Chippy feels the need to Chipp-ify the city, and in doing so try to get a sense of who he is.

In many ways, Chippy is a character that's as old as urbanism. He’s a flaneur, a drifter walking, always walking, and on the lookout for spots where he can tag or climb or both. He’s also a romantic, at times a hopeless one.

For Valentine’s Day, he hung a hanging basket off a lamppost in the middle of the city and left a love letter to his girlfriend in it.

“But obviously no one could read the love letter hanging from a lamppost. It was in an envelope, sealed,” he tells us.

If that seems pointless, it’s no more pointless than tagging. And there is something sweet about it.

Chippy says he has a code, but like most mortals, it’s a code that he breaks. He says public buildings and private houses are off limits, which leads to a conversation about the Shakey Bridge, where he has a tag on the wall leading up the bridge and on the bridge itself.

At this point, I tell him his code is flexible, and Chippy bristles a little. The way he sees it, there's graffiti and tags all around the bridge, so what’s one more?

“You know what, I feel like Shakey Bridge will always be Shakey bridge, I’m not taking a part of it away. I feel like people are too traditional sometimes.”

Another Chippy tag in Blackpool is on the wall at the end of a public laneway lined with houses. Again it spells Chippy. I ask him what he thinks about residents having to look at his tag every day. The short answer is Chippy hasn’t thought about it much. It’s just a tag.

“Everyone’s nice here”

Sounding very much like a parent (hey, but also a journalist), I ask Chippy about school and what’s coming next.

The conversation on school is short, and you sense that those were far from the best days of his young life, possibly some of the worst. As for what’s next? That’s a blank canvas. For now, there is no grand plan other than doing what he’s been doing. He’s not going to graduate into a graffiti artist; by his own telling he’s not an artist - to which Cord Reddit would no doubt agree.

Like a pop singer being interviewed for every other interview, Chippy’s prone to some rather sweet but empty-sounding pronouncements. He says he’d like to do more romance graffiti, along the lines of Chippy Loves Ya, “because it's true, I love this city and everyone in it. Everyone’s nice here.”

We leave Chippy back on Patrick’s Street near the spot where he would most like to leave his mark. It’s a testament to how much Chippy looks up, or that I don’t, that he’s spotted it. It’s a billboard space that’s been empty for years, and if Chippy ever manages to get up there and tag it without getting caught or falling off and seriously injuring himself, you’ll definitely notice it.

For a few minutes, we talk about the route up to the empty billboard space. Chippy has given it some thought, but it’s very doubtful he’ll leave his mark there; it’s too risky. But if he did, would we even see the unassuming Chippy because, as he says, “Nobody looks up, I look down on them from the roofs, wondering what’s going on in their lives that they don’t look up.”

For the meantime, that’s one space that he can’t leave his message to Cork: Chippy Loves Ya.

-JJ

Tripe+Drisheen meets Conor Harrington

True story: For the title of my final year dissertation I gave it the grandiloquent title “Towards an analysis of public art”. Twenty years on I couldn’t tell you the first thing that’s in there and I pity the poor lecturer who had to suffer through it, but I was mighty…

This tagger has vandalised tens of thousands of euro of public and private property in Cork City making it look tatty and tired. As many of us try to fight against the dereliction in the city this is a desperately depressing article. He even admits his tags are devoid of any artistic merit (as is the majority of graffiti). This is the equivalent of a dog lifting its leg and peeing around the city. I and so many other despise every one of his tags. Why do you need to tell everybody about your 'achievement' when you climb up a building? Film yourself climbing it and put it online instead of trying to destroy our city.

And the BS about not destroying heritage buildings. You put one on the first floor of the beautiful French Connection building on Patrick Street. Absolutely pointless and enraging for those of us who love our city.

Nice to hear from CHIPPY <3