Car-free in Cork: week three

A week of two halves, from cooped up working from home to the wilds of the Burren....but how can rural Ireland go car free with transport links that are sketchy at best, and can we bring back rail?

Freelance life is full of insecurity and stress but it’s also got its perks: I’m writing this morning from Doolin in Co Clare, where I’ve been since Thursday evening.

I was a plus one while my partner worked at a very pleasant little winter festival called Hedge School, which combines workshops aimed at musicians, in things like synthesiser and pedal manufacture, with a diverse array of other musical and literary offerings, interspersed with musical and theatrical performances and banging tunes at night.

Of course I have my laptop on hand and have to periodically attend to work but after a start to the week where car-free was really beginning to feel restrictive and arduous, I jumped at the opportunity to get the hell out of Dodge for a few days.

It’s also a good way to take a look at how rural transport is working, or not working. Transport horror stories are rife amongst the festival chat: I speak to a film director who describes his epic carless voyage from the Inishowen peninsula in Donegal to attend the festival….via Dublin. A friend from West Cork who was attending had to get a bus from Clonakilty to Cork city, another from Cork to Ennis, and a further bus from Ennis to Doolin.

Dublin is of course a transport hub, but connecting via Dublin for trips on the West coast is insanity.

I once booked a train ticket from Cork to Mayo and arrived in the station to discover that the journey was going to take nearly nine hours because it was going via Dublin.

Connectivity

When it comes to rural Ireland, it’s very hard to see how a transition away from some form of personalised motor transport is possible at present, with such a small population scattered over such big distances.

You just can’t provide a door-to-door transport service in many remote places without incredible cost: it would be like running a taxi service.

Are Electric Vehicles the solution? There’s an idea for continuing a grant scheme for EVs in rural locations, but very sketchy detail as to how this would be administered. Farming families that have trialled EVs have pointed to the lack of charging points as a major barrier, but there’s a plan to invest €100 million in charging points in the next three years.

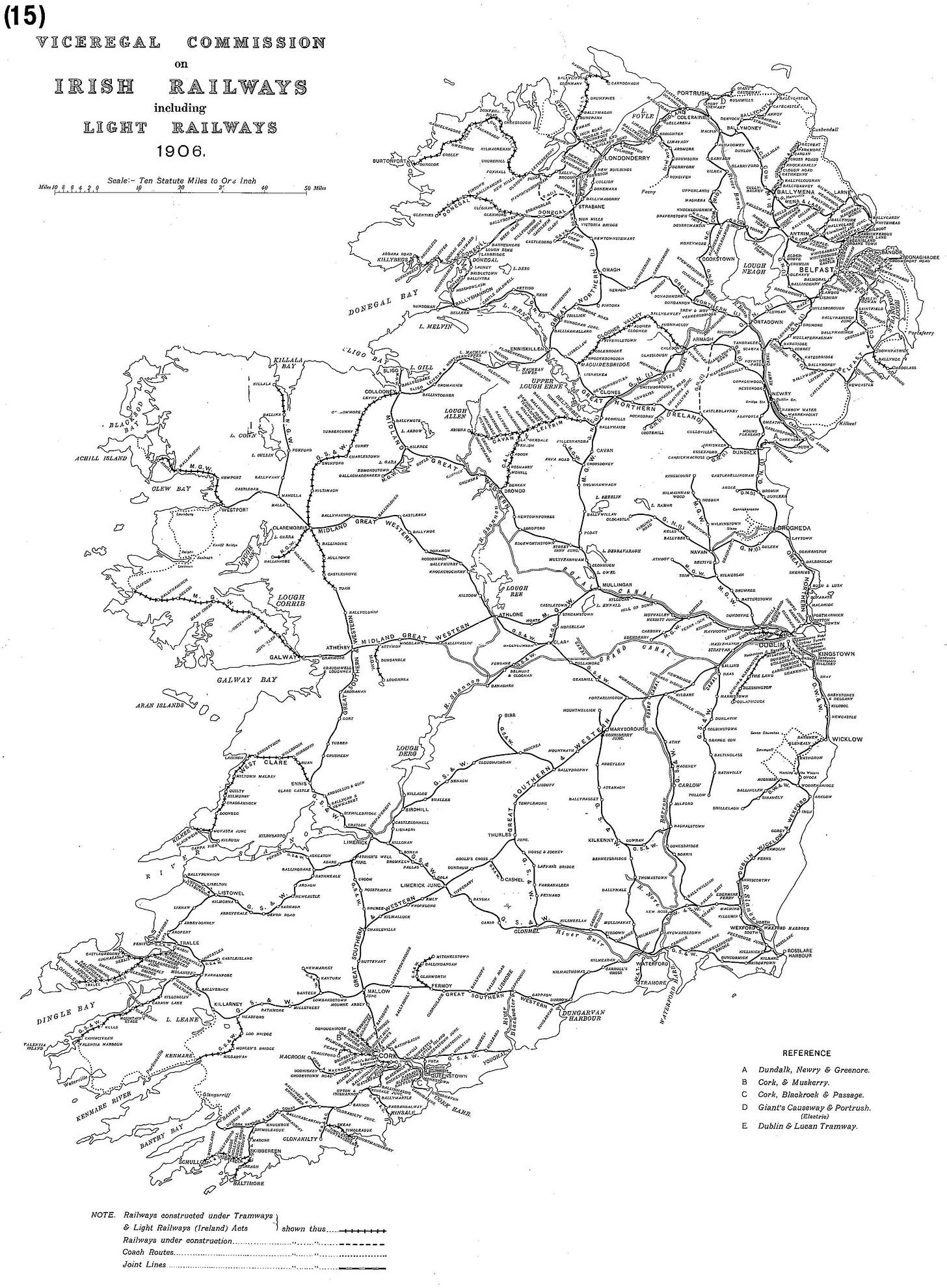

In an ideal world, there would be heavy investment in restoring the rail network that has been so shamefully abandoned, neglected and dismantled by successive Irish governments throughout the history of the state, that a restored rail service would be connected to a Local Link bus service. And, of course, a bike carriage on every train.

It’s pretty crazy to think that the people I spoke to who had such difficult and arduous journeys to Co Clare this weekend would have had been served by a more efficient rail network 118 years ago than they are today, including my newfound friend in Donegal, who now has no rail options at all since the closure of the Great Northern Line 60 years ago.

In fact, a campaign to have a rail service restored in much-neglected Donegal was launched last year.

Rural Ireland, far-flung parts of Cork county included, are battling for investment, to halt and reverse rural decline, to cling on to their hard-won tourism income. And it’s an incredible uphill battle when they’re often not served by any reliable transport links to speak of.

Even this morning in Clare, preparing to leave, a part of the hotel that was supposed to be open and serving breakfast was still locked and in darkness quarter of an hour after they were supposed to start serving, all because staff coming from nearby Lisdoonvarna were waiting on a bus that was late.

Week three

Monday and Tuesday: I only leave the house once, on Monday morning, to cycle the 4km round trip to the nearest shop to get a few necessary groceries. It’s about 8.40 when I’m whizzing down the hill past the bus stop and my heart sinks when I see the enormous queue at the stop and, sure enough, my daughter’s blonde head in there. She set off half an hour ago, but it looks like she’s going to be late for school again. She shrugs helplessly at me as I go past.

Everything seems like a great deal of effort at the start of the week and, to be honest, my mood is low. I have a list of further flung interviews and article ideas that I’m just not getting to and I feel that my freedom is being considerably restricted, that the resource of my time is being eroded beyond what’s sustainable. I do all my interviews online at home, via Zoom: it’s horribly reminiscent of the nightmarish world of 2020 and 2021.

Of course, it was during Covid lockdowns that the idea of working from home (WFH) as a carbon-saving measure began to take root in the hive mind. Although we talked a lot about the right to work from home, though, we didn’t talk much about the right not to work from home.

But as someone that has worked from home for a long time, I feel well placed to comment on the downsides of WFH. Digital does not replace real, in the first instance: interviews, classes and meetings via video call are observably more exhausting that the real-life kind, in part because our brains are working harder at threading together communicative cues that are intuitive and unconscious in the real world.

In the second place, for anyone without ample space to be able to have an actual home office, working from home can be a kind of torment, especially in combination with parenting demands.

And in the third place, there are unforeseen consequences of WFH: it may not even be all that much better for the environment, and it’s leading to a massive shift in the pattern of how space is used in our cities: Lisney reports that Cork is expected to soon start experiencing the phenomenon of “Grey Space” - office sub-lets - as multinationals continue to cut costs, or offset them onto their employees, by moving to a blend of WFH and office work.

Wednesday: I need to go into the city centre in the afternoon, but I decide to do it by bus instead of on my bike to see how public transport measures up: I haven’t been using the buses because of their irregularity.

I walk up the road to the 208 stop and am pleasantly surprised that the bus arrives almost immediately. The driver tells me Wednesday afternoons are "mental” because it’s half day for secondary kids. It takes 37 minutes to make it into town, whereas it’s 25 minutes by bike. Once in town, walking between locations and then waiting for a bus home also takes time: in total, I reckon I am an hour down because I bussed instead of cycled.

The verdict is that bike beats bus for speed, anywhere within about a 5 km radius of the city centre. Whether the National Transport Authority’s Bus Connects plan can change that, and how the enormous spend and the carbon footprint of construction projects will eventually be justified and measured is a matter of keen interest to me.

Thursday:

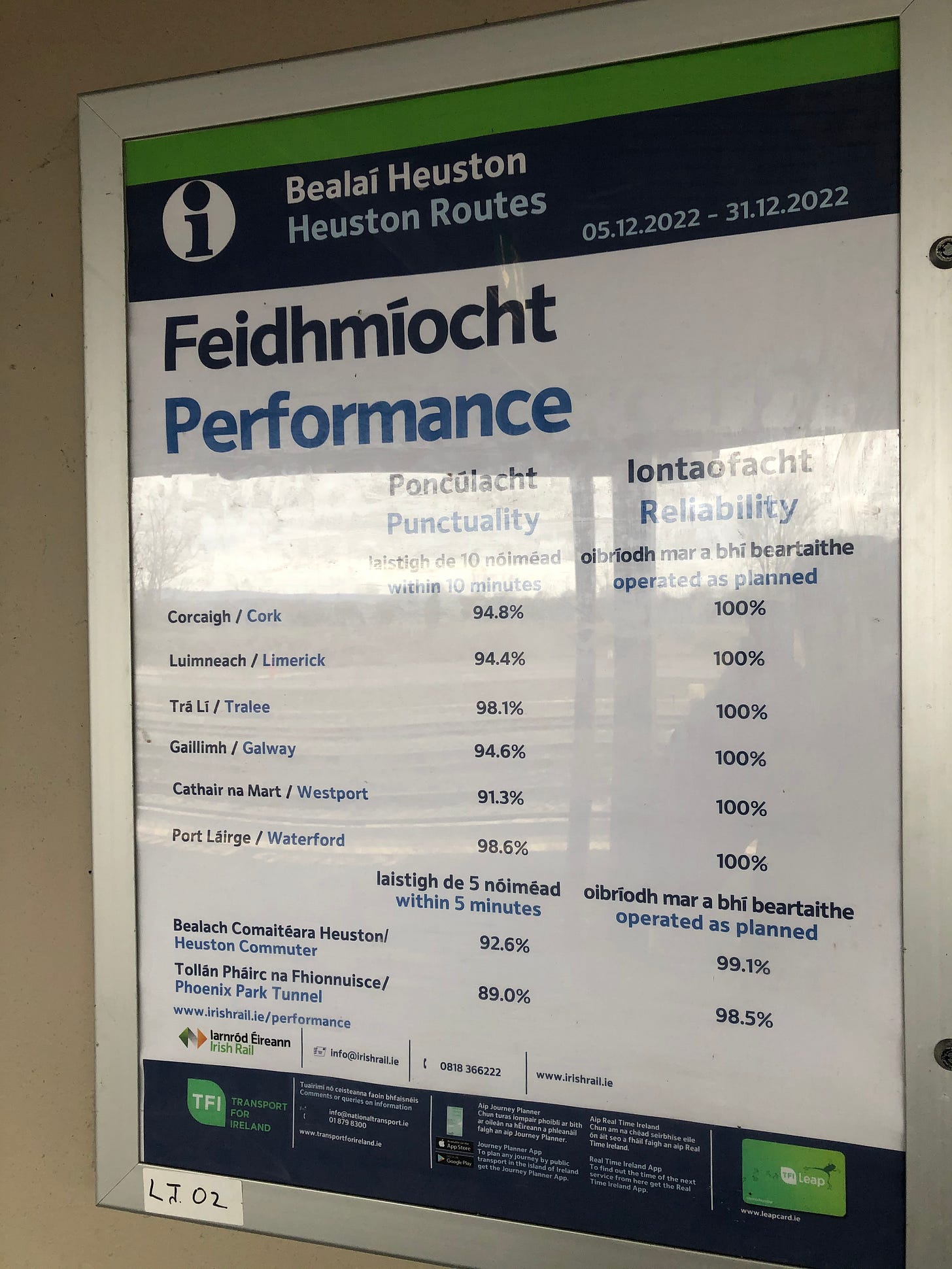

I put my bike on the train from Cork to Limerick Junction at lunchtime. My partner is driving to the festival in Clare from his home in Waterford and so, rather than him having to go out of his way and go to Clare via Cork, I meet him halfway, marvelling both at the fact that Limerick Junction is actually in Co Tipperary and at the poster in the station:

Surely “as planned” would include “on time”? What possible other criteria could there be for the running of a train? The fact that it didn’t derail?

My bike is coming too because we’re planning on making the most of the weekend by getting out and about and enjoying the rugged beauty of the Banner county.

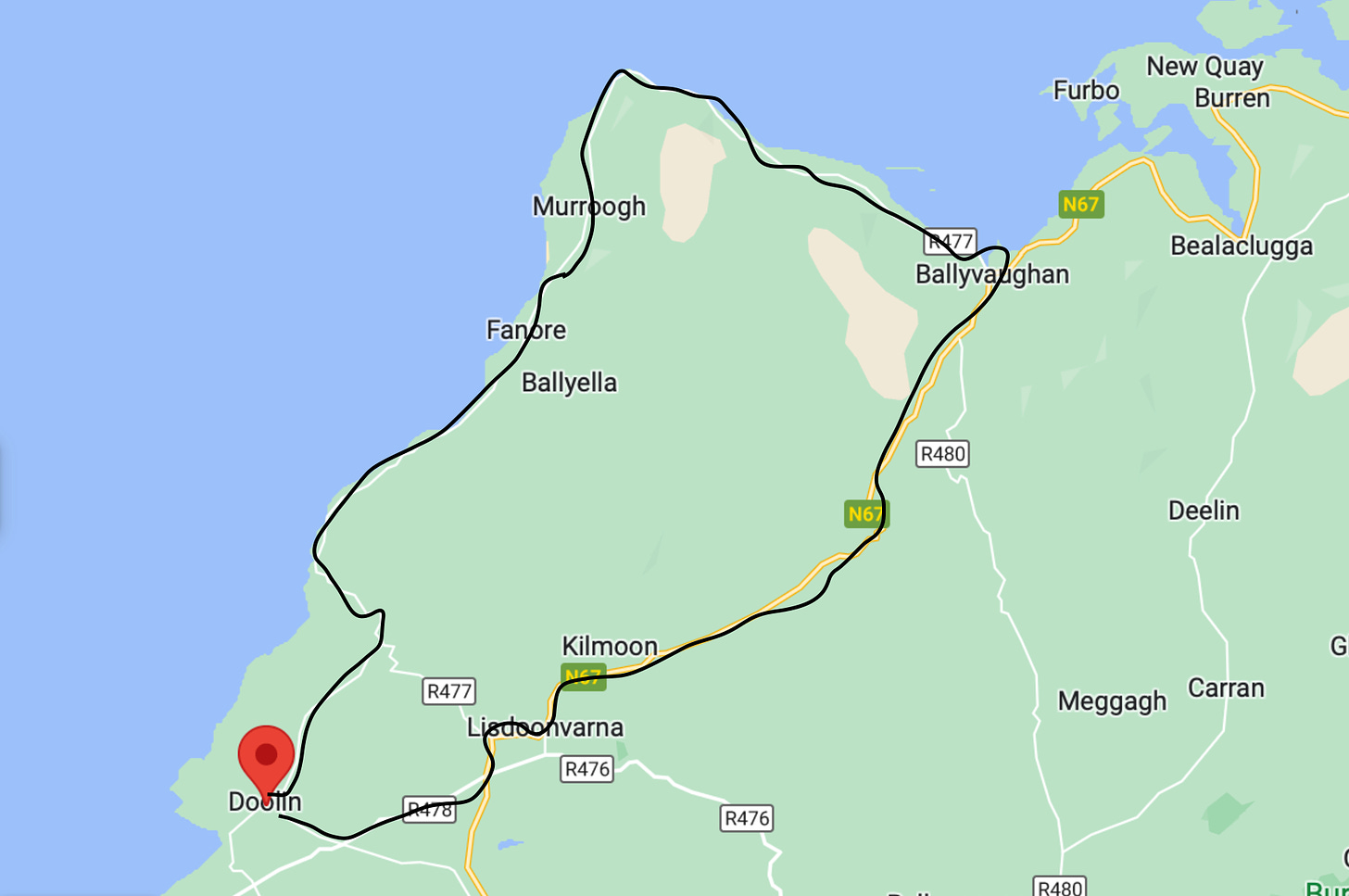

Friday: Before the festival events kick off, we go on a little cycling loop from Doolin through Fanore, Ballyvaghan and Lisdoonvarna. It’s gorgeous, and lovely to be cycling for pleasure, spinning along past the curious faces of little brown cows, the crags and boulders and lichened crevices of one of Ireland’s most magical landscapes.

The loop is just under 60km, with a steep climb up Corkscrew Hill between Ballyvaghan and Lisdoonvarna, and resulting views down over Galway Bay. Bliss. I have a little chuckle to myself: In an afternoon, I’ve cycled more for pleasure than I did all last week for the purposes of getting from A to B.

Saturday and Sunday: We’re festivalling all day Saturday. Sunday morning, we give a lift to a festival guest the 40 mins to Ennis in order for him to get a bus back to Dublin. On the way back, we pick up a hitcher, who is headed to Galway: he says he hitches all the time, but that most people don’t stop any more.

Long before GoCar, hitching was an accepted and very viable form of car-sharing in rural parts, but it’s increasingly uncommon both to see people thumbing and for people to stop and offer lifts. I make an inner resolution that, if I ever go back to car ownership, I will pick up more hitchers.

In the afternoon we ditch the bikes in favour of a walk: there are parts of the Clare coastline you’ll miss even by bike, and we hop like awestruck mountain goats from megalith to megalith along the flaggy shore in the mist and the spray, overlooking the islands and the distant Cliffs of Moher ….sometimes our feet are the only transport we need.

Brilliant article again ,Ellie !!