Blinded by the light

Anonymous artist GUBU Man has been unable to tolerate LED light for the past decade: exiled from the online world as a result, he has a dystopian warning for us about our connected lives.

It might seem like a blessing rather than a curse: the anonymous Dublin artist known as GUBU Man has never laid eyes on a Kardashian.

Although he may foster a hope that one of their famous arses may actually do what they promised to and “break the internet.”

For the past ten years, GUBU Man has suffered from LED sensitivity. LED lighting in computer screens, smartphones, indoor and street lighting make him feel nauseous, dizzy: “Have you ever had concussion?” he asks. “It’s like concussion.”

When he initially began to react to LEDs, he went to his GP, who arranged a battery of tests and scans.

“It all came back fine, so there was no brain anomaly behind it,” he says. “I went to the Mater Hospital and I saw a doctor who explained to me about how LED light flickers.”

LED lights use a system called Pulse Width Modulation to save energy which means they are essentially flickering very quickly all the time. It seems to be this phenomenon that causes some people to experience migraine-like symptoms when exposed to them.

GUBU Man stockpiles old incandescent lightbulbs for his house, but going out can be difficult.

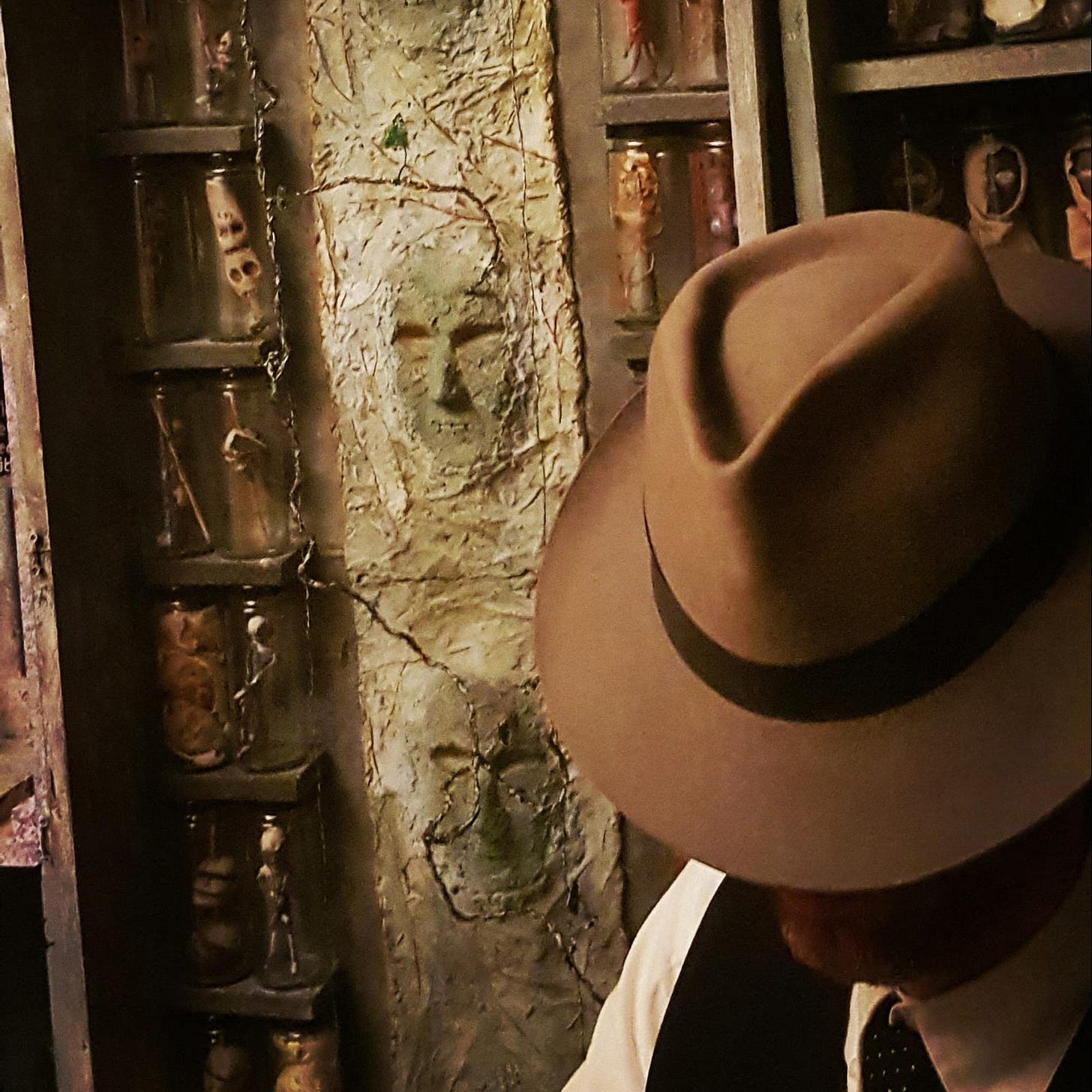

“When I go out, I wear a hat and dark glasses to protect me from street lamps and car headlights,” he says. “LED is everywhere and it’s inescapable. If I have to go in somewhere very bright I’ll actually put on blackout glasses and use a cane and normally staff will help me.”

But of course, LED lighting is increasingly ubiquitous as a low energy source of lighting. A large project is currently underway to replace street lighting throughout Ireland with LED lamps. In Dublin, where GUBU Man lives and works, it’s estimated that the local authority will save €1.5 million in energy costs per year once a four-year project to replace some 40,000 street lights is complete.

GUBU Man and other sufferers of LED sensitivity, however rare they may be, do exist. And on the street lighting issue, they feel like they have been sacrificed on the altar of the common good, without many people noticing.

“We’ve totally overhauled our whole lighting system almost overnight, and without much research,” GUBU Man says. “They knew it would be damaging to some people, but they rolled it out anyway. It’s an extraordinary experiment.”

To some people who are unaffected by the phenomenon, people like GUBU Man may seem to be experiencing a psychiatric condition rather than a physical state: as is common with so many who experience rare conditions, he has been treated as though it’s all in his mind. But not by doctors or people who work with technology.

“It’s almost an easy answer if someone is acting in a non-normative way to just say, ‘they’re mad’ instead of asking yourself how your behaviour is affecting them, isn’t it?” he says. “It’s not as bad now, but ten years ago people just couldn’t fathom it.”

“Medical people thought in terms of epilepsy and stuff like that, and I had friends who worked with computers who immediately understood that this was a pulse width modulation problem, the way the light is flickering. But a lot of people have just thought I’m a bit mad: in person, I come across as relatively sane, but people who see my art might think it’s a bit crazy.”

An exile from the online world

To read this Tripe + Drisheen article, GUBU Man tells me, he will ask a family member to print it off.

He buys newspapers, and his sole direct connection to the online world is through a smart speaker and Alexa. He can use voice commands to listen to podcasts and audio books. Other than that, he is a exile from the online world.

All around him, people are glued to their devices. “In terms of information, I’m not part of that onslaught of snippets of information that people get with push notifications on their phones,” he says.

But it’s also increasingly difficult to access any State or banking services, any official information, if you can’t use a smartphone.

“It’s very difficult to get around without it,” he says. “I have family and friends to help me out with that sort of thing, but it’s kind of like not being able to read or something.”

He has an Instagram account and a website for his art, administered by family. But his choice to be anonymous when presenting his art is partly informed by this inability to connect online.

“I’m cut off from all of that,” he says. “I can’t function online and that’s very frustrating. If I had people contacting me on the internet I’d find that very frustrating. So I use a pseudonym to protect myself. That way I can step back from it, people can say whatever they want and it’s nothing to do with me. I don’t have to be dragged into it or feel like I have to try to reply or to force myself to use computers.”

A journey into the world of GUBU

In his pre-LED sensitivity life, GUBU Man was a writer, of books and plays. But presenting books to be published without using computers is now a near impossibility. So GUBU Man began to produce what he calls “a novel out of clay.” He turned to sculpture to construct a fantastical, dystopian civilisation.

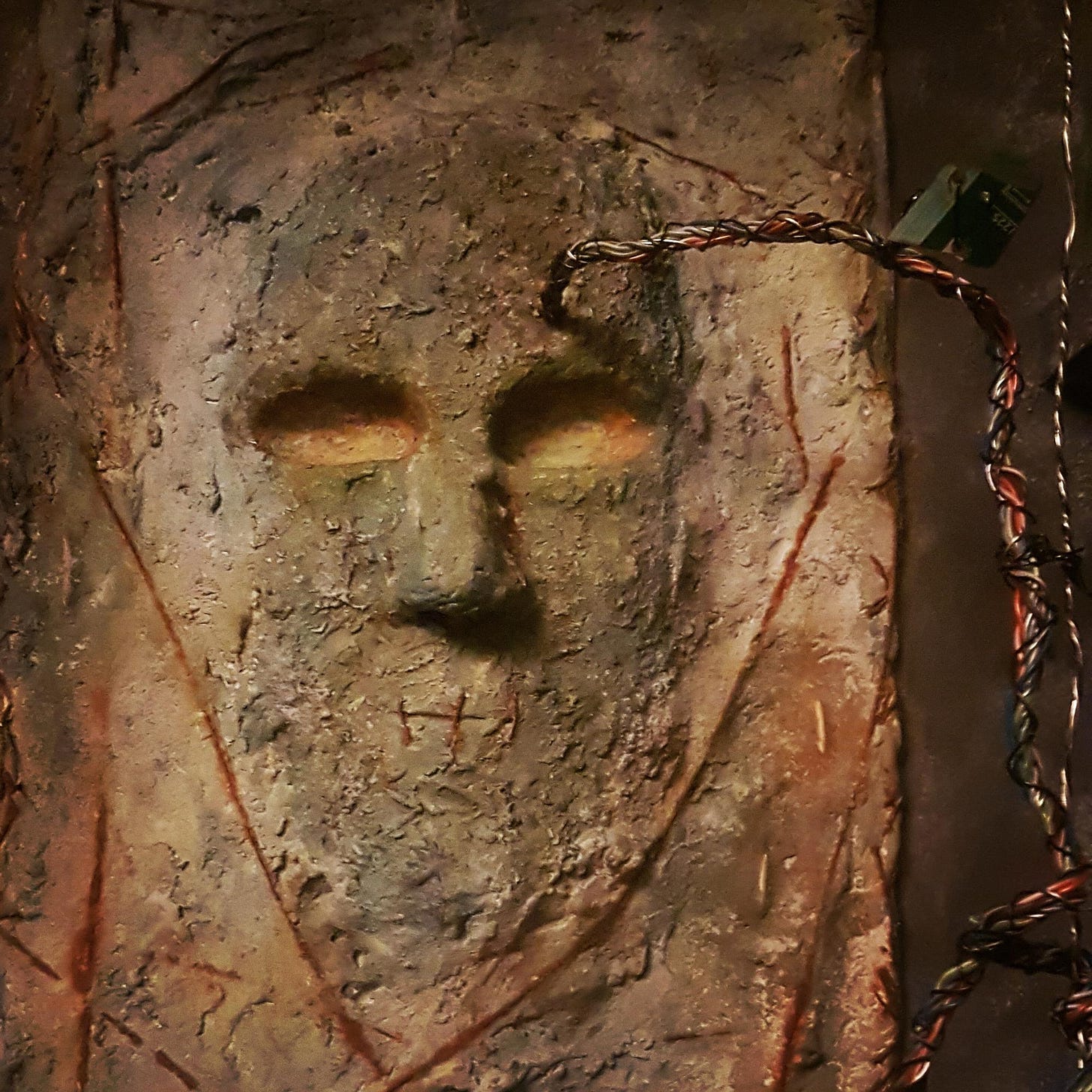

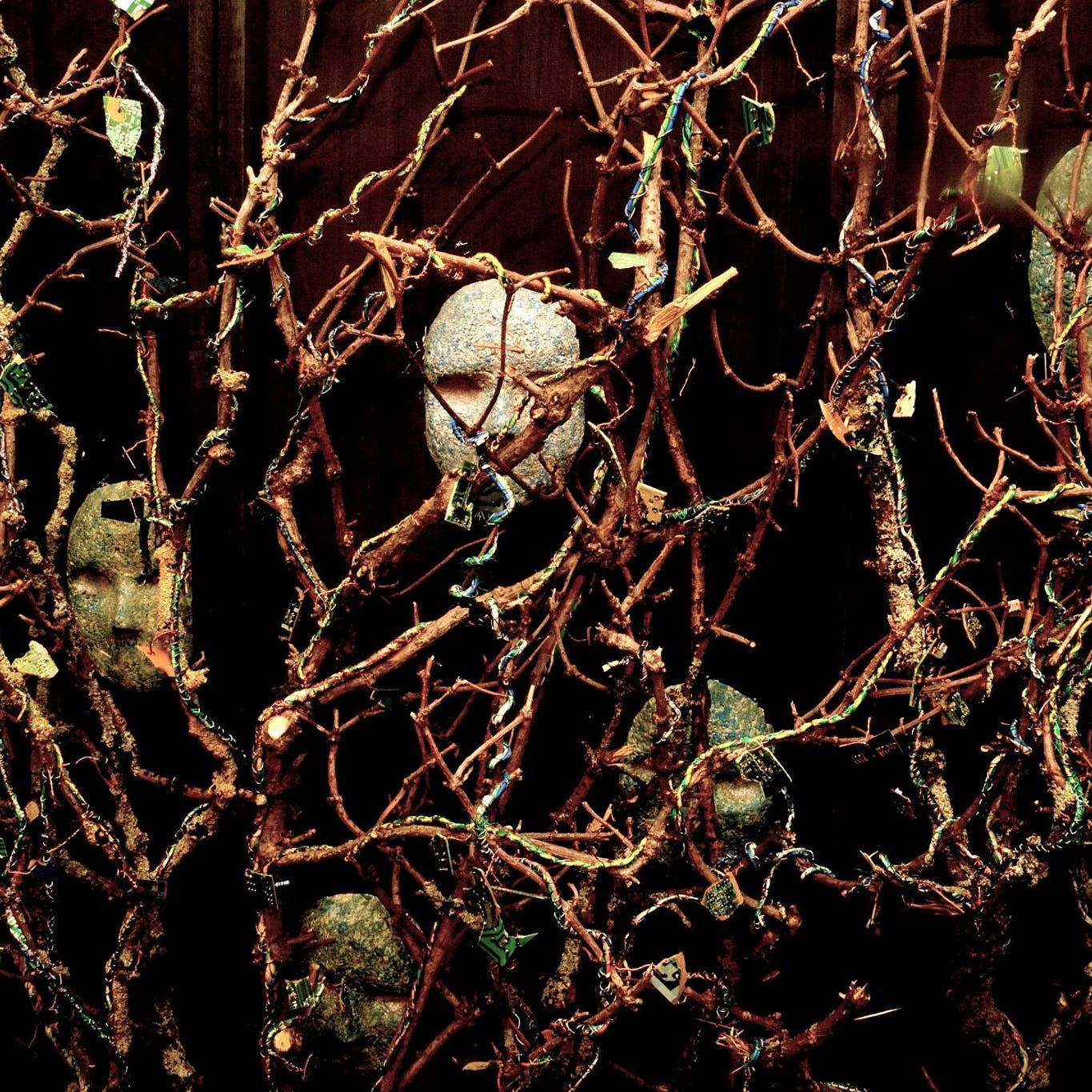

He set about building little dolls, mostly out of found objects and materials and frequently incorporating waste electronic components. Simultaneously, he was constructing a complex narrative surrounding these creatures, which he calls GUBU Dolls after the Irish political term Grotesque, Unusual, Bizarre and Unprecedented.

A permanent exhibition containing at least 500 GUBU dolls is now housed in an installation in Dublin’s Gallery X called The GUBU Saga.

It’s a complex and horrifying world, populated with mythological creatures, religious iconography and a doctor who is experimenting on the minds of his charges by connecting them to a “telepathic internet.”

“I tell the story of the people who have gone through this experiment and are now connected to the telepathic internet all the time,” he says. “I’ve put a lot of thought into the religious aspect of it. I wanted to make a complete culture for them, their own philosophy and religion.”

“I have a tree in there, the Axis Mundi, the tree of life. The roots of the tree reach down into the depths of the earth and the branches reach into the sky so you can connect with the Gods. But my tree has wires wrapped around it representing the Technium, technology. It’s wondering if technology is strangling the tree of life, or is it a branch of the tree of life? It’s almost like tech is becoming a superhighway to the divine; the wires wrapped around the tree of life will connect it.”

Outsider Art

GUBU Man is a self-styled outsider artist, not only because of his exile from the world of the online, but also because GUBU Man is himself a character, a theatrical element to the making of art.

“I don’t know what the cool kids were doing in London six months ago, I don’t know what’s happening on the internet,” he says. “But I thought to myself, I know narrative so that’s what I’ll stick to; I’ll make a book out of physical objects. I get into character and then I make the things that that character would want to make.”

Is the GUBU world a warning, based on his outsider observations of an increasingly connected way of life? “I don’t know if it’s a warning,” he says. “But the rate of tech acceleration in recent years is amazing.”

“My exhibition has attracted some very interesting viewers, people who work in tech and who have been inside the data centres and google research centres and everything. Some of the wild stuff they tell me is just incredible: it’s quasi-mystical, all of that stuff about The Singularity. Like a weird religion.”

The acceleration towards The Singularity

The rate at which technology has advanced in the past decade that GUBU Man has been offline is, for him, a cause for alarm, not least because of the concentration of power in the hands of a few tech billionaires. There are strong resonances here with his own experience of technological change leading to powerlessness.

“There are computers now that you can, in essence, control with the mind,” he tells me. “There’s the Metaverse and everything. Who knows where we’ll be in 20 years time.”

“A handful of billionaires decided this. There was no vote - they never asked the rest of us. You listen to an interview with someone like Elon Musk and he’s talking about how AIs will happen but, yeah, there’s a good chance they could do a lot of damage to humanity. They’re building them anyway, and there’s no say in it.”

“The whole idea of AIs? it’s an order of intelligence that we can’t even calculate. We kind of imagine that they’ll be like Terminator, like a very powerful human, but it could be just something inexplicable that we can’t understand.”

GUBU Man is Dublin-based, but he has had an outpost of his GUBU world on display in Cork for the past two weeks, closing today: the New Reality exhibition of Contemporary Collage in St Peter’s Church has contained a reliquary of his making.

“I often make things in little boxes, where it feels like you’re thrown into someone’s world,'“ he says. “I have time, because I can’t watch television or look at computers, so I spend hours and hours making art, endless hours just working away. With the installation in Gallery X, I probably put 10,000 hours into it, easy.”

In the future, GUBU Man hopes that the problem of LED sensitivity will be solved. “Hopefully it will be fixed, or they’ll come up with some new technology or glasses that will make screens safer,” he says.

In the meantime, like so many other artists, he seeks solace in his work, and even finds healing in it.

“When this hit me, I had this tactile need to make things with my hands. There’s a notion that people with brain injuries or anomalies often turn to arts and crafts and that this could be the brain trying to repair itself, to remake neural pathways.”

“I don’t whether that’s true or not, but I find it a compelling idea.”

One of GUBU Man’s works is on show in Cork, but only until Monday, October 24. He is exhibiting as part of the New Reality Contemporary Collage exhibition on the mezzanine in St Peter’s on North Main St. You can visit his permanent GUBU Saga installation in Dublin’s Gallery X on Hume St.