Beasts for the East?

The beaches and beauty spots of East Cork are within easy reach of Cork City, but their future may be under threat from intensive agriculture.

Is East Cork set to become the front line in an ideological battle on the future of Irish agriculture?

With two big environmental disputes related to industrial agribusiness underway in the east of the county, even as the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) offers stark warnings about the impacts of intensifying agriculture on water quality and other environmental markers, East Cork, home to so many beaches beloved of Cork city slickers, seems to be standing at a crossroads.

Near Midleton, locals are pondering whether to contest the industrial waste licence the EPA has granted to a cheese factory to pump four million litres of wastewater per day, laden with 60kg of FOG (Fats, Oils and Greases) into the sluggish waters and mudflats of Cork’s inner harbour.

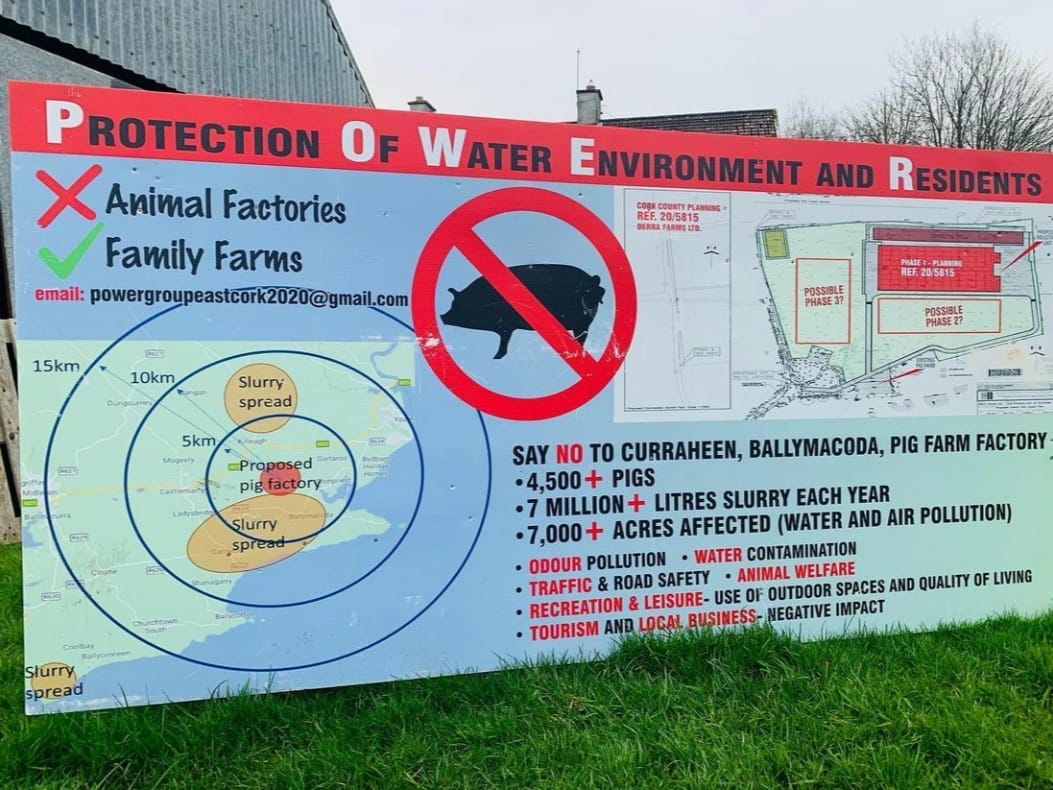

Meanwhile, in Ballymacoda, roughly halfway between Ballycotton and Youghal, the planning consultation process for an industrial piggery of up to 4,500 animals, which would produce seven million litres of pig slurry per year, is about to close.

These local struggles are occurring against a pivotal national backdrop.

Two weeks ago, the only environmental stakeholder at negotiations for Ireland’s Agri-food Strategy to 2030 walked away from the table, blasting the process for its shamelessly tokenistic approach to sustainability and environmental conservation.

A brief glimpse at the make-up of the 32-member committee announced by then-Minister of Agriculture Micheal Creed in November 2019 should leave no confusion as to why, in the words of Karen Cielenski from Environmental Pillar, the draft strategy “did not facilitate any meaningful public participation on the future of Irish land use.”

Directors and CEOs of Glanbia, Dawn Foods, Diageo, Keelings, Carroll’s Meats, Kerry Group, Musgraves, Ulster Bank, catering multinational Sodexo, and for some bizarre reason, Envecon, a digitalization firm that has worked with Microsoft, Oracle and energy companies.

More bean-counter than bean-grower, Creed’s statement as to the overwhelming success of decades of such strategies tells its own tale: “agri-food” is business. Success is measured not in the amount of nutritious foods provided to Irish eaters at a fair price to farmers and other workers (take another look at that list: Carroll’s and Keelings, both of which were involved in two of the biggest food industry scandals of Covid, no less) or the ability of Irish farmers to ensure soil is sustainable for future generations of food producers.

“The success of these strategies is evidenced by a 73% growth in agri-food exports since 2009,” Creed pronounced, before adding a token “and of course environment, blah blah” bit at the end.

Minister Creed appointed umbrella group Environmental Pillar, almost as an afterthought, as the single entity representing environmental concerns, if you discount the presence of Laura Burke from the EPA.

Not that the EPA hasn’t been flip-flopping backwards and forwards between granting emissions licences and issuing dire environmental warnings of its own.

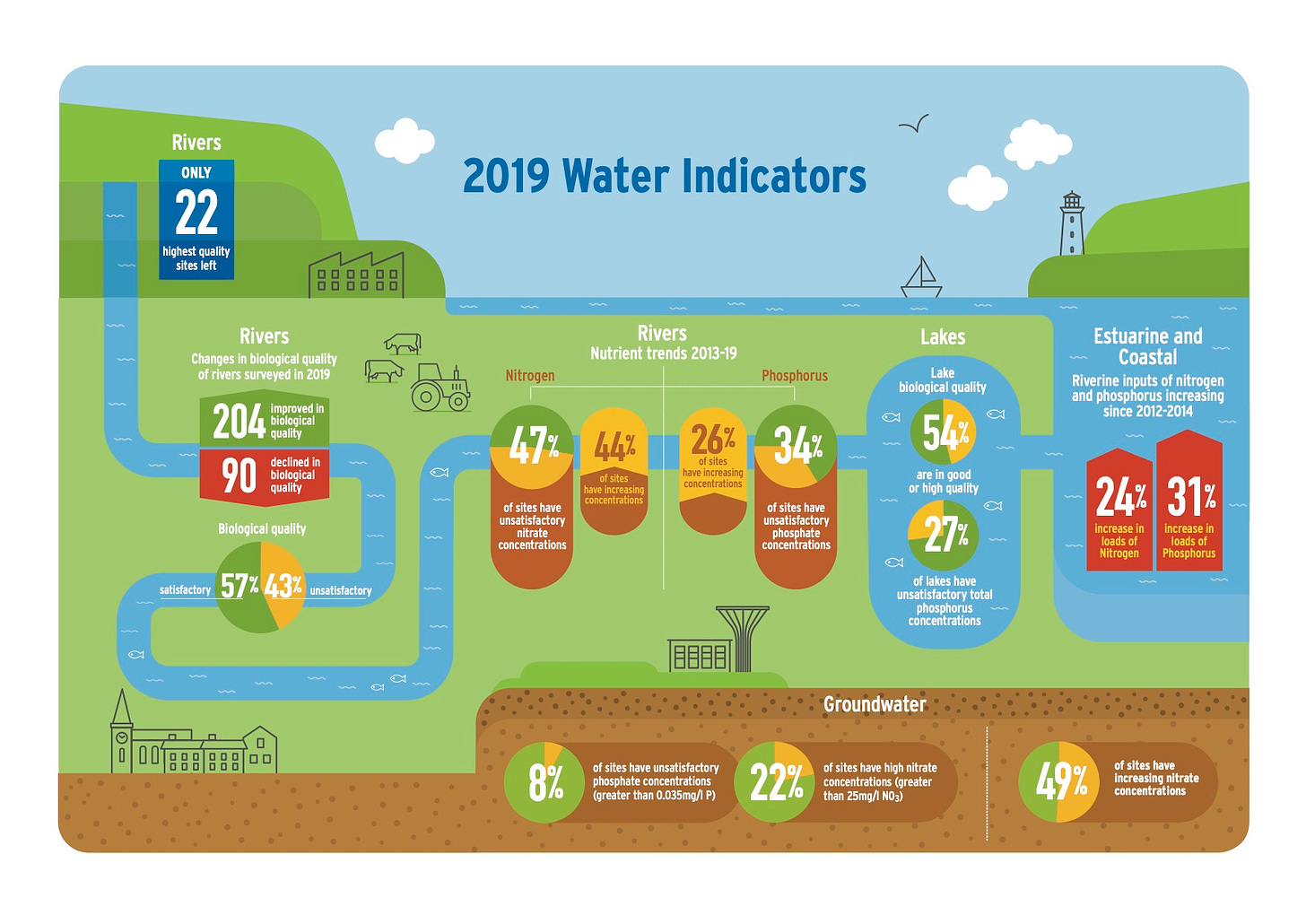

In a press release following the publication of the EPA 2019 Water Quality Indicators Report in December, EPA director Dr Micheál Lehane and programme manager Mary Gurrie were as explicit as employees of a state agency can be in pointing the finger squarely at agriculture. “Urgent action is now needed to reduce nutrient inputs from agriculture,” Ms Gurrie said.

The report revealed a shameful 24% increase in nitrogen loads to coastal waters, and a 31% increase in phosphorus loads, within seven years.

That’s just the sea. When it comes to rivers, the Republic of Ireland now has just 22 pristine watercourses left.

We are in the midst of what journalist Ella McSweeney has termed “a water pollution crisis” – a silent tide that we’re all ignoring. Agricultural intensification policies that put profits in the hands of export giants and commodify our food chain are, make no mistake, a large part of the problem.

Discussing the EPA water report, EPA Director Dr Micheál Lehane said: “This assessment shows that our water environment remains under considerable pressure from human activities. Of most concern is the continued upward trend of nitrate concentrations. The problem is particularly evident in the south and southeast of the country where the main source is agriculture.”

Yet on February 19, despite more than 60 submissions of objection from groups and private citizens, the EPA granted an Industrial Emissions Licence to Dairygold and TINE Ireland, who will be making Jarlsberg Cheese for export, to discharge four million litres of industrial effluent through 14km of heated pipes into the inner harbour at Rathcoursey.

For local campaigners, the licensing process felt like a sealed deal: Dairygold constructed the 14km pipeline from its €120 million plant at Mogeely to its discharge point at Rathcoursey before being granted their license, as was highlighted in an article by Christy Parker in the Irish Examiner.

Bitterly disappointed with the decision, the group spearheading the campaign, Protect East Ferry Waters, is not talking right now, but is weighing up options for future actions.

On, then - most fittingly for Tripe + Drisheen - to pigs

An industrial piggery of some 4,224 pigs may bring home the bacon for Philip O’Brien of Derra Farms, but it would result in seven million litres of pig slurry per year for East Cork residents.

Planning documents lodged in August 2020 propose demolishing the current 1,000 animal operation at Ballymacoda (actually just 220 sows and their offspring) and replacing it with a far more intensive 4,224, but in some parts of the application 4,500, “finisher” pigs.

Derra Farms Ltd has a further 1,000 animals in Mitchelstown, North Cork. Mr O’Brien has a LinkedIn profile which lists him as an IFA Pig and Pigmeat Committee member.

The potential for water pollution is acknowledged in the planning application. The majestic Blackwater River is close to the site, the Womanagh River, just 800m away. Four designated Special Areas of Conservation lie within 15km, as well as many of East Cork’s most popular amenities and beauty spots.

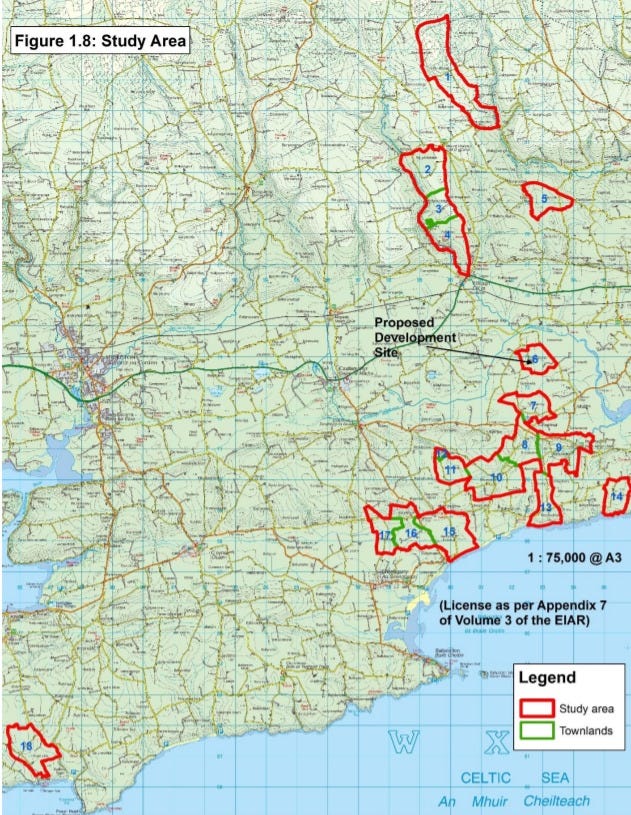

It is proposed that pig slurry from the farm will be spread over fields in 18 townlands, many adjacent to the sea.

From 4,224 pigs, to one…

Colleen Phillips has one pig. She’s called Doris. “Yeah, I’m just not telling Doris about what’s going on,” Colleen jokes on the phone to me.

Colleen and her partner, Fabrizio Vitali, run Inch Hideaway, an ecotourism business that’s taken ten years to build. True to its name, Inch Hideaway is located within easy reach of Inch Beach, a short strand popular with local surfers.

It’s also smack bang in the middle of one of the townlands where it’s proposed that some of the seven million litres of pig slurry generated at the Ballymacoda piggery would be spread.

Colleen and Fabrizio’s yurt glamping business is made up of five units that can comfortably sleep 25, where holistic therapies, pizza nights and guided foraging walks are on offer. It’s also home to their smallholding: vegetables and chickens. Despite the presence of Doris, one can easily imagine that this little idyll would not exactly be enriched by the odour of industrial quantities of pig slurry.

Run-off

The farms surrounding Inch Hideaway do already spread manure and slurry, but most commonly, that’s from cows, Colleen tells me. “Around here, it’s usually what they clean out from the cattle sheds at the end of the winter season,” she says. “It gets ploughed in and they put tillage crops down.”

“I was saying to a neighbour, ‘you know, I don’t really have a problem with slurry and manure,’ and he said, ‘Colleen, have you ever smelled pig slurry? It’s horrific.”

Several streams complete their journey across farmland to the sea at Inch beach. Colleen tells me that in wet weather, these contain clearly visible run-off.

“These fields are so worked that when there’s a deluge, everything runs off them,” she says. “You’ve got those nitrates running across the roads, down into the streams. We’ve even got a stream running across our field, and all those streams run right to Inch.”

“We’re in a bit of a dip, that has always been called the boggy field,” Colleen says. “And it’s called the boggy field because we have run-off from all the land around us. So we’d be fairly affected by it.”

Colleen and Fabrizio have a good relationship with their farming neighbours, who, Colleen is keen to stress, are very accommodating of their business: “They will wait to spread stuff when the wind isn’t blowing into the campsite, or they’ll avoid ploughing late at night when people are sleeping, so we have a really good working relationship with them.”

Pig slurry is a potent source of ammonia and nitrogen, which causes eutrophication: essentially, too many nutrients in the water, leading to deoxygenation, algal blooms and other environmental harms.

But, as Colleen points out, an industrial pig farm of the scale of the one proposed for Ballymacoda will be using large quantities of antibiotics and other veterinary medicines, a risk factor identified nowhere in the Environmental Impact Assessment submitted with Derra Farms’ planning application.

“They feed them antibiotics all the time because they’re in such horrible living conditions,” Colleen says. “The whole idea of that type of farming, I’m just massively against. I think it’s a really horrific way to farm animals.”

Antibiotic resistance

Of course, pigs, like all animals, and like humans, excrete the medicines put into their bodies. Pharmaceutical water pollution is a poorly understood area, but one of growing concern, not least when it comes to the threat posed by antibiotic resistance.

This is all a far cry from the future Colleen would like to see, not only for her, she points out, but for the many others reliant on tourism.

“It’s not just us; there are loads of people who rent out their houses or who use this area as a holiday destination, and not just in the summer,” she says.

“All the beaches are less than an hour away from Cork city and it’s beautiful here. People might have always headed west, but more and more people are coming down here. There’s surfing and kitesurfing here, and a lot more people are using the local natural amenities that we have.”

Colleen notes the hard work from organisations such as SECAD, a local development group, and the East Cork tourism board which has gone into promoting the region as a tourism destination.

“They’ve been putting so much money and effort into promoting tourism in this area that this feels kind of like a step backwards,” she says.

Just busy fools

So what would Colleen consider to be a step forwards, then? “There’s quite a foodie thing going on in East Cork and there’s been quite a lot of awareness about supporting a local, circular economy,” she says.

“This is really good arable land, tillage land that could be supplying our local economy. It could be about actually reducing things, slowing them down and keeping things local. Otherwise we’re just busy fools, ruining our really good resources.”

More POWER to you

POWER, the loose affiliation of East Cork residents who have joined forces to fight the piggery planning application, have launched an online petition to raise awareness, but, Karen O’Donohoe tells me, the clock is ticking for anyone interested in lodging a formal objection as part of the planning process.

The deadline for submissions is the 18th of March.

“We’d like people to be informed and to take action,” Karen says, speaking on Zoom with the noisy clatter of her family life in the background. She sits forward earnestly, runs her hands through her hair. “Use your voice! Whether you’re from the area, or visit the area, or share our concerns around animal welfare, whatever: please spend the €20 and take the time to make a submission.”

Karen will be familiar to many as the co-presenter of RTE’s Grow, Cook, Eat show. She’s also a resident of Ballycotton. She works for Waterford-based social enterprise GIY (Grow It Yourself), so issues relating to food policy are things she’s well used to thinking about, but in this instance, she’s keen to stress that she’s talking in a personal capacity.

When it comes to the animal welfare concerns Karen has raised, the Environmental Impact Assessment submitted on behalf of Derra Farms Ltd tells its own tale.

2,250 pigs will be housed in each of two “fattening houses,” each with a footprint of 2455m2: taking into account walkways to access pens, this means around one metre squared of living space per animal. The application lists an anticipated 70 tonnes of carcass waste per year from “normal mortality.”

Presiding over this quantity of pigs, it’s anticipated that the work-force on the site with increase from one employee...to two.

“Two people, looking after 4,200 pigs? That’s not looking after the pigs. That’s looking after business,” Karen says. “Animals can be reared in a regenerative way, in a way that is at least respectful. We don’t feel that what’s proposed here is respectful of people, or the planet, and certainly not the pigs.”

“We had only become aware of the planning application by chance, to be perfectly honest,” said Karen.

“This is quite a significant proposal, but we only became aware of it because a local woman who is in the process of getting planning for a new home went to check on the progress of her application and spotted it.”

“As a community, for lots and lots of different reasons, we’re very concerned. We all have different reasons for objecting. Certainly there’s the animal welfare perspective, there’s the environment, but also let’s just think about the smell. This is a beautiful part of the world and the reality is that bringing in a factory of this scale is of huge concern.”

East Cork’s charms are increasingly apparent both to tourists and denizens of Cork city, but supporting and promoting the east of the county as a place to visit comes at no small cost. Cork County Council have just invested €19.8 million in a new Midleton to Youghal Greenway, which will run just 1.6km away from the proposed pig factory.

“At the moment, we have so much to celebrate here,” Karen says. “It’s a beautiful part of the world and we have amazing food production. People always say Ballymaloe, but it’s not just Ballymaloe that’s operating to the highest standards in food production.”

But that beauty and fertility can’t be taken for granted: set against the backdrop of the dairy-heavy farming already in place, Karen certainly sees the POWER group’s goals as part of a bigger picture. And like Colleen, she believes the future should be focused on quality foods for smaller, closer markets, and a mix of small businesses rooted in the communities of the harbour towns.

“The way East Cork is operating isn’t good enough as it is,” she says. “We feel it would be better to improve the way we live and produce and consume first, before bringing in yet another stressor for the local environment. There’s a climate crisis happening, a biodiversity crisis.”

For Karen, then, East Cork is indeed at that frontline I so dramatically referred at the outset of this piece. If intensive agribusiness, and a future of still more intensification, is what lies ahead for communities all over the country, keeping a close eye on how things unfold for POWER and other community groups motivated to protect their environment is a wise move.

“We’re objecting here in East Cork, but we’re aware of all the other communities who are living with thousands of pigs being intensively reared on their doorstep, and that’s just not sustainable food production,” Karen says.

“What’s happening here for us at the moment is a really good example of the hypocrisy of what people in Government and different state agencies say needs to be done, versus the realities of big agri-food business and the social, environmental and economic disaster that it can be.”

Juri Herteljust now

I'm the neighbour of dump No.5, my name is Juri Hertel.

My postcode is P36YA62, check this yourself via google maps.My lands are the green spot in the agricultural dessert you can see there.

I run a vegetarian organic farm and I don't want to be doused in the shite of this concentration camp. The water from my well is clean so far, according to the map in the article above my drinking water well is just 50 or 60 meters away .... I hope this map is a fake. But then the planning application would be faulty. And who is the faker, who has drawn these lines?!