Aramark and the English Market

The English Market is the jewel in the crown of Cork's foodie culture. So why is it managed by a company notorious for its US prison food and management of direct provision centres in Ireland?

The English Market’s luscious heaps of fresh local produce are Exhibit A in the case for Cork as food capital of Ireland.

But the little-known fact that the day-to-day management of the gourmand’s paradise is in the hands of a company notorious for its US prison food and management of Irish direct provision centres may leave a bad taste in the mouth of some visitors.

US food and property services giant Aramark has been dogged by controversy for years.

Cork City Council has renewed Aramark’s contract to manage the day-to-day running of the English Market twice under an open procurement process, most recently in 2017.

US prisons

From maggots and roaches found in food served to prisoners in Ohio, Michigan and California, to its use of prison labour and position as subcontracted food vendor and uniform provider for immigration detention (ICE) and border patrol services, the company’s US track record has been particularly controversial.

12% of the company’s $12.5 billion in revenue in 2020 was from its US prison operations, where it holds a 38% market share of the lucrative business of American prison catering contracts.

While reported incidents, including riots caused by the quality of the food in a Kentucky jail, date back years, and while Aramark has had contracts cancelled in several US states, some reports are more recent, including this one from an inmate in a California prison last November.

Irish direct provision

From humble beginnings as a California vending machine company in the 1930s (ARA stands for Automatic Retailers of America, and the company only became known as Aramark in 1994), Aramark has grown to become the vast global enterprise it is today.

Aramark Northern Europe now employs 16,000 people, at least 6,500 of these in Ireland. The company’s UK and Ireland focus is possibly in part directed by the fact that the president of Aramark’s Northern European division is an Irishman.

Here in Ireland, Aramark has been Ireland’s largest, but strangely invisible, catering company for over a decade, employing a policy of both horizontal and vertical acquisition, and running franchises for multiple well-known brands. It’s also the country’s largest dedicated property management company.

Aramark Ireland Holdings Ltd holds contracts for on-site catering, cleaning and property management in three of Ireland’s direct provision centres.

Aramark was paid €5.89 million for operating direct provision centres at Knockalisheen in Co Clare, Kinsale Road Co Cork and Lissywollen in Co Westmeath in 2018, according to this report by The Irish Examiner’s Aoife Moore.

They have operated Cork’s largest Direct Provision centre at Kinsale Road since 2016.

At Knockalisheen Accommodation Centre in Co Clare, reports of a mother being denied access to the canteen by Aramark staff to get bread and milk for her sick child sparked protests at the nearby University of Limerick, where Aramark also run catering facilities, in 2018. Knockalisheen has been the centre of several disputes based on food and living conditions, including a hunger strike in 2015.

Between 2014 and 2018, Aramark was paid €9.5 million to run Lissywollen direct provision centre in Co Westmeath; in 2014, residents of Lissywollen also undertook a brief hunger strike in protest against “small portion sizes, poor hygiene, and unacceptable living standards.”

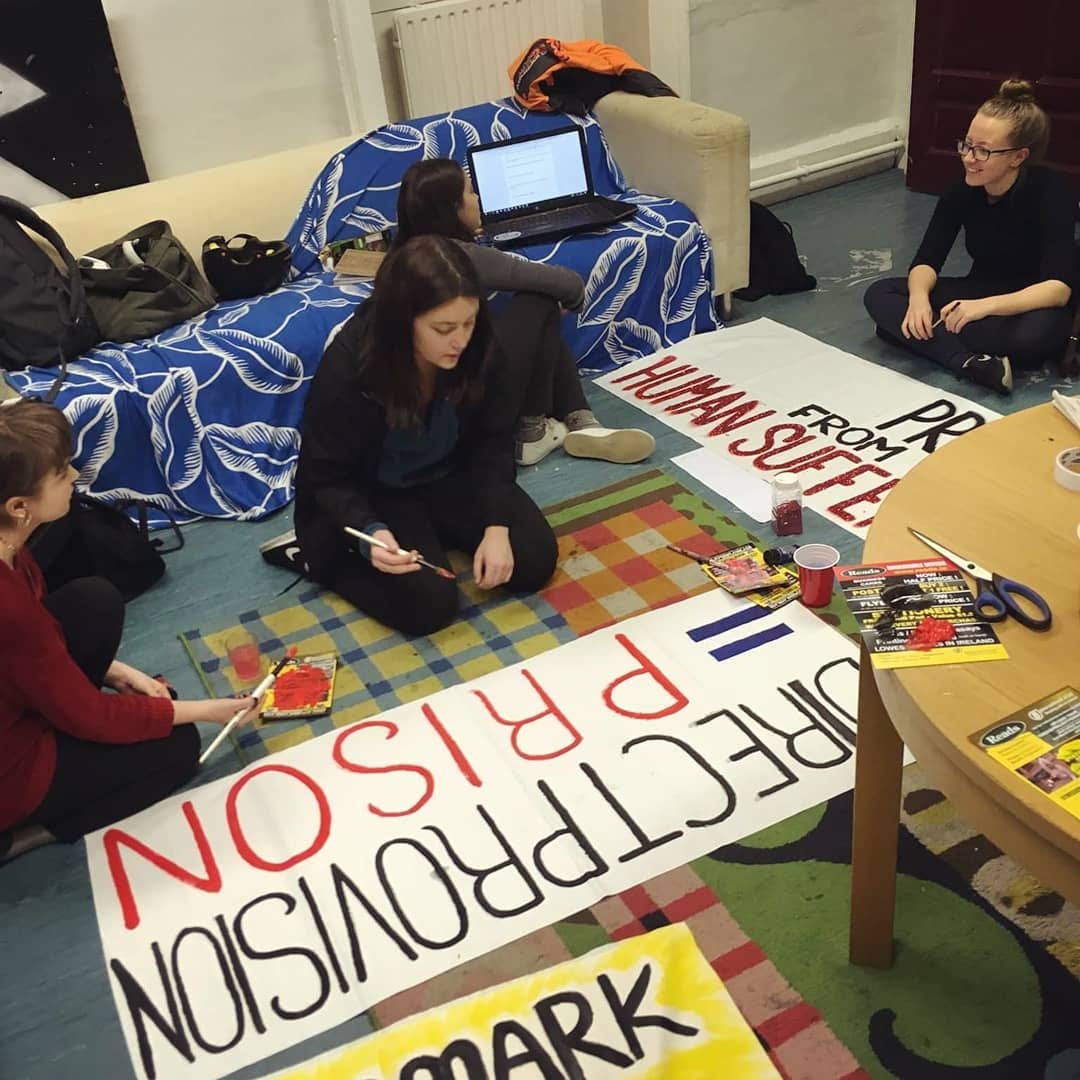

College protests and boycott

Jessie Dolliver, a student from Turner’s Cross, is currently finishing her MA in Zoology in Trinity College: after, she will go on to do her PhD in Oxford.

Jessie spent summers and weekends throughout secondary school and into third level working in the Real Olive Company in the English Market.

As an undergraduate in Trinity, she also co-founded the successful Aramark Off Our Campus campaign: in December 2019, Aramark terminated its contract with the Dublin college’s catering services, where it was running student café services which are now being provided by in-house staff, according to reporting from the UT.

Months later, Aramark also left UCD, saying that the decision was a commercial one.

Alongside her co-founder, Stacey Wren, Jessie picketed the Trinity café run by Aramark, distributed flyers about direct provision and generally raised hell, but Aramark do not accept that student activism played any role in their decision to leave Trinity.

“Aramark left early, but when we said on social media that they had left because of our campaign, they said our campaign was ‘not a factor’ in their decision to leave,” Jessie tells me.

“But from our experience, they were being disturbed by our campaign. I had one of Aramark’s managers message me privately on Facebook trying to set up a meeting, which was really inappropriate, and they printed information leaflets after we started protesting outside their cafe and they were intimidating in general. So we like to think the protests contributed to them leaving.”

Knowing that Aramark held the reins in their contract with Trinity College, Jessie and Stacey’s campaign focused directly on “trying to make the café unprofitable so they would decide to leave because it’s bad business: a boycott, basically.”

While US college campuses are running similar campaigns, Jessie’s interest in direct provision in Ireland sparked her decision to protest against Aramark’s presence at Trinity.

“We thought it was quite hypocritical of Trinity to be positioning itself as an agent for social change and progression and at the same time be in business with Aramark who are, I believe, in violation of human rights,” she says.

A source of pride and a source of shame?

Jessie was always aware that Aramark also managed the English Market, where she worked throughout her teens, doling out delicacies for one of the market’s most popular stalls.

“It was always a bit uncomfortable working there and knowing Aramark are managing it,” she says.

“I definitely find it ironic that the English Market is something all Cork people are so proud of, and if you were to connect it to the human rights violations that occur in direct provision, that’s something for Ireland to be ashamed of.”

“But I definitely feel that people aren’t aware of the atrocities that are happening in these centres because they are intentionally placed where contact with others in difficult, in places with poor bus connections for example. I don’t think it’s an accident that people who are so proud of the English Market aren’t aware of this.”

Readers should know that Aramark are not involved in any catering or food provision in the English Market: Aramark Property management are a division of the company that handle property and asset management, and in the English Market, they’re responsible for hiring cleaning staff, arranging maintenance and services.

A Trinity-style boycott would not be in any way an appropriate form of action, Jessie is keen to highlight: “Obviously, you don’t want a boycott against the small, family-owned businesses in the market.”

But even though Aramark are not dishing up meals in the English Market, Jessie thinks it’s really not a good look for Cork’s food Mecca, with its connotations of fresh, local, seasonal, sustainable, ethical nutritious produce, to be managed by a global company with Aramark’s track record when it comes to feeding humans.

“This is a company that has cut portion sizes for profit, served gone-off food,” she says. “They’re obviously not the best people to be the care-takers of such an important cultural component of Cork as the English Market. A local business would be better suited.”

Aramark from the horses’ mouth: “The food was shit”

Photos of plates of nutrient-less, flavourless stodge - heaps of clumping rice, damp slices of white sliced pan - grace the MASI (Movement of Asylum Seekers in Ireland) Facebook page. Most pictures have no caption, so how many of these are from Aramark-run centres it’s hard to tell.

I call a contact who has been through the direct provision system. I ask him if he can put me in touch with someone with experience of an Aramark-managed facility, but he can go one better: he lived in Knockalisheen Accommodation Centre himself. He doesn’t want to be identified, so we will call him Joseph.

How was the food?

“Shit,” he says bluntly. “The food was shit.”

“They serve the same food every day, despite them having the option, like they have in other centres, to have a points system so people can buy ingredients and cook themselves. They don’t want that because it will reduce the profit they can get from their contracts.”

He recounts a tale whereby a friend knocked on the kitchen door during the scheduled lunchtime because no-one was serving, and witnessed a staff member cleaning dirt from the kitchen floor with his bare hands. The staff member then came out and began serving residents without washing his hands: asked by residents to don gloves, the staff member became hostile.

It’s not only food and hygiene issues that reared their head: Joseph reports a generally hostile environment, where receptionists were rude and disdainful, and where family members of staff were offered jobs with no training or experience.

“The employees Aramark hired were not experienced or in my opinion, eligible to work with vulnerable people and people from different backgrounds,” he says.

“The worst experiences I’ve had in my entire life were in the Knockalisheen centre,” Joseph says. “It’s a shame on the Irish government that they contracted a company like that to provide direct provision, that has such a shameful history in America.”

Love me, tender….

Cork City Council puts out a tender for the management of the English Market.

They have employed private management agencies to oversee the market’s day-to-day operations since the 1980s, a council PR representative confirmed to me in an email.

“Aramark became managing agent following their acquisition of Irish Estates Management,” the email reads. “They were again successful in securing the contract, through open procurement processes, in 2012 and 2017. This contract is still in place.

”The role of the managing agent is to provide onsite property management services and to assist and collaborate with Cork City Council and the market traders to strategically develop the English Market's unique offering.”

Cork city councillor Fiona Ryan intends to put in a motion proposing that Aramark not be considered for future tenders for the management of the English Market “in the first meeting of the new year,” she tells me.

The Solidarity-PBP councillor has previously written a letter to the Cork city executive on the issue. “But I think that it’s something that should have been raised in a formal sense prior to now.”

She says Aramark’s involvement with the English Market is “absolutely out of keeping with the image we want to promote of the English Market. Anyone can see reports on social media from residents of the direct provision centres run by Aramark on the low quality of food.

“I think it’s an example of the executive putting a price tag on engaging with a company that has been engaged in systems of what I would deem as abuse, not just here in Ireland, but in the US.”

The Irish direct provision system is set for replacement, under the terms of a white paper published by government last February.

The recommendations of the white paper include that any reception service for refugees and migrants be directly run by the state and not by profit-making companies. To Fiona, this is a tacit acknowledgement that the profiteering we’ve seen within direct provision is part of the broader problem of privatising services that need to exist not for profit, but for the public good.

“Once you have a profit motive on something like direct provision, the only people that can lose are the residents,” she says. “The government may be dragging their heels, but they’ve acknowledged the fundamental flaws with having a for-profit system when dealing with the day-to-day care of human beings who have a right to human dignity.”

Fiona acknowledges that Cork City Council must apply tendering best practice to get the best value for public money, but she doesn’t accept that Aramark’s track record, both in Ireland and internationally, should be ignored.

“I think Cork City Council should be taking a role in leading on these things,” she says. “The bottom line of the tendering process doesn’t take into account the social obligation on the council, and I think Aramark running the English Market is in conflict with our social obligations.”

Not just the English Market

To be fair, Aramark run a whole lot more in Ireland than the English Market. You might well eat in an Aramark-run café, garage forecourt or college canteen, but you probably won’t know it: Aramark operate franchises, so you’ll be eating in a Chopped, a Subway, or a Costa.

In 2016, Aramark acquired Avoca Handweavers. They also bought out Campbell catering, the company behind the iconic Bewley’s brand, in 2005.

The company say they have been behind an “organised campaign questioning our role in providing important food and nutrition for people that are in the justice system.” They are large employers, and they provide nutrition and other vital services.

“Aramark strives to create a better world by carefully considering our company’s environmental, economic, social and ethical impact on our dedicated employees and the communities we serve,” they say in a “Get the Facts” page on their international website.

I emailed the Aramark employee listed by Cork City Council’s website as the point of contact for the English Market, but curiously, she told me she was “not allowed to discuss any Aramark business.”

She must have meant press queries, because she offered to refer me to their PR department, who had not responded by the time we published this story.

“Future-proofing” the English Market for generations of traders and customers

Pat O’Connell of O’Connell’s fish stall is, of course, the face of the English Market: Barack Obama, Queen Lizzie and other British Royals and visiting dignitaries have all been brought for an audience with the great man.

The long-standing chair of the English Market Traders’ Association, Pat resigned this role recently in the hopes that “a younger person from one of the traders’ families will come along and take up the mantle,” he tells me over the phone, with the bustle of his busy stall behind him.

While Pat is aware of some of the controversies surrounding Aramark, he says their day-to-day management of the English Market is smooth and that the company have a reasonably good on-the-ground presence.

“Listen, the traders will always have a few complaints about how the market is being managed, but we’ve had various different groups running the market and we’ve had worse than Aramark,” he says.

“I wouldn’t be a big fan of the huge American companies myself, but that’s just a personal view. I’ve heard about things like the direct provision, but they’re a huge company with services across the board.”

Far more important, from Pat’s perspective, is Cork City Council’s role as holder of the purse-strings. Ambitious plans to make the English Market more sustainable and better able to cater to both tourists and regular shoppers would “future-proof it for the next 50 years,” Pat says.

But that would take a very large amount of investment.

“We’ve done a lot of work on all sorts of plans,” he says. “Ways of making the market greener: the roof badly needs replacing, so we were looking at a rooftop market garden, where produce could be grown to sell downstairs. We were looking at solar panels, rainwater collection systems for things like washing the floors. We were looking at an organic waste composting system.”

Investment in the English Market is investment in the food culture of Cork’s future, Pat believes; he regularly hears comments from UK and French visitors that it’s nice to visit the English Market because their own markets have shut.

Whether the independent, local, sustainable aspirations of many for the long-term future of the English Market are best-served by the management of a global multinational catering company like Aramark remains to be seen, but for Pat, the priority is protecting and building on the historic and much-loved market’s place in Cork’s life.

“I would like the English Market to be the number one food market in Europe,” Pat says. “We have something so unique here, with the same families running stalls for generations, with the local producers. These are the things that we want to protect. And now’s the time to do it.”

I knew nothing about Aramark, despite shopping in the English market for over 40 years. This was an eye opener