AirBnB in Cork: how big a role is it playing in the housing crisis?

There are 1,089 short-term lettings in Cork city and county right now, and 62 long-term homes to rent; is AirBnB the disruptive innovator that's truly disrupting our housing market?

Some facts:

1,548 active properties in Cork city and county are advertised on short-term letting platforms AirBnB and Vrbo today, March 31.

98% of these properties are on AirBnB

70%, 1,089 of these are entire homes that may be suited to long-term tenancies

There are 62 rental properties in all of Cork city and county advertised on Daft.ie today. Several of these are duplicates.

A change in law was introduced in 2019 meaning property owners had to apply for planning permission for change of use if they were AirBnBing a property for longer than three months of the year.

51 change-of-use planning applications have been made to Cork City Council and Cork County Council in the three years since the law was changed.

19 of these have been granted, all by Cork County Council.

From small beginnings…

It’s a familiarly goofy tech-bro origin story for one of those internet giants that began as enthusiastic disruptive innovators but would go on to change the very fabric of 21st century life: what and where we eat or buy consumer goods, or even where and how we can afford to live.

It’s a little like Mark Zuckerberg and his college roommates founding a website where they could keep tabs on the pretty girls on campus, or Jeff Bezos starting to sell stuff from his garage.

In 2007, Brian Chesky and his “roommate, Joe” decided to inflate a couple of air mattresses and turn their apartment into “an airbed and breakfast.” Airbed and breakfast: AirBnB, see? A platform was born, founded on the pleasant notion that homeowners could make a few extra bob by extending a warm welcome to guests a few times per year, as it suited them.

“Our guests arrived as strangers but they left as our friends,” AirBnB CEO Chesky, now 41 and worth $13.8 billion, told his shareholders at a difficult earnings call at the end of 2020. “And the connections we made that weekend made us realise maybe there's a bigger idea here.”

But from well-intentioned, almost utopian beginnings, AirBnB today has proven itself a large scale disruptor of domestic property markets. It’s a trend that even the temporary set-back of Covid-19 hasn’t curbed.

Fast-forward to 2022, and Chesky is telling us that the global impacts of working from home during Covid-19 mean that ”travelling and living are starting to blur,” saying he wants to feel “part of a community” when he indulges in a nomadic lifestyle, living in different AirBnBs for a couple of weeks at a time. This, of course, is lunacy. You can’t summon up a sense of community overnight as part of a consumerist smorgasbord of trendy lifestyle perks.

And plenty of communities have been rallying against the impacts of AirBnB rentals in their areas. In many cases, for many years.

In Ireland, the conversation about the profound change AirBnB is having is lagging behind the times: in the US, the impacts of AirBnB on the housing market were being discussed (and written about) back in 2014. Alarm bells rang for New York activist and technologist Murray Cox around the same time, and he built a website called Inside AirBnB to make openly available the kinds of trends you will read about in this article.

Allowing landlords to make multiples of what they could earn through letting to long-term tenants in short-term holiday lettings, while allowing them to circumvent inconvenient paperwork and, up until February 2021, even tax bills, has an unsurprising impact on the amount of housing stock available in the rental market.

The private rental market plays an important role in providing homes.

And housing NGOs are warning that, if we think the housing crisis has been bleak so far, we can’t even comprehend what’s about to hit us.

Daft situation

Threshold, the national tenants’ rights NGO, issued a press release this month with the above demographic: in Co Cork, there were over ten times the number of whole homes - which would be suitable as long-term rental accommodation - advertised on AirBnB and its competitor, Vrbo, as there were homes advertised for rent on Daft.ie at the time they took the snapshot.

What if I told you that today, the situation is already far, far worse?

This is partly seasonal: I used the same tool as Threshold analysts did in December 2021, short-term letting analytics website AirDNA, but now, in spring, there are 1,089 entire homes advertised for short-term letting.

There are 88 entire homes advertised on AirBnB in Cork city, and just 31 on Daft.ie.

“We wanted to highlight this issue because there are actually plenty of properties there, but landlords are choosing the short-term route because it’s better for them,” Edel Conlon, manager of the Cork branch of Threshold, tells me.

Exactly how much more lucrative can AirBnB be?

€71,000 for Cork’s AirBnB hostess with the mostest

AirBnB revenues can be enormous for those willing to put the work in.

The top earner on Cork city AirBnB, according to AirDNA, is a five-bed house near Turner’s Cross whose host puts away a staggering €71,400 per year. Two-beds are generating upwards of €40,000 per year for their hosts, as you can see from the AirDNA screengrab below: a two-bed “historic hideaway” behind St Fin Barre’s Cathedral comes in as second highest earner at €47,500 per year.

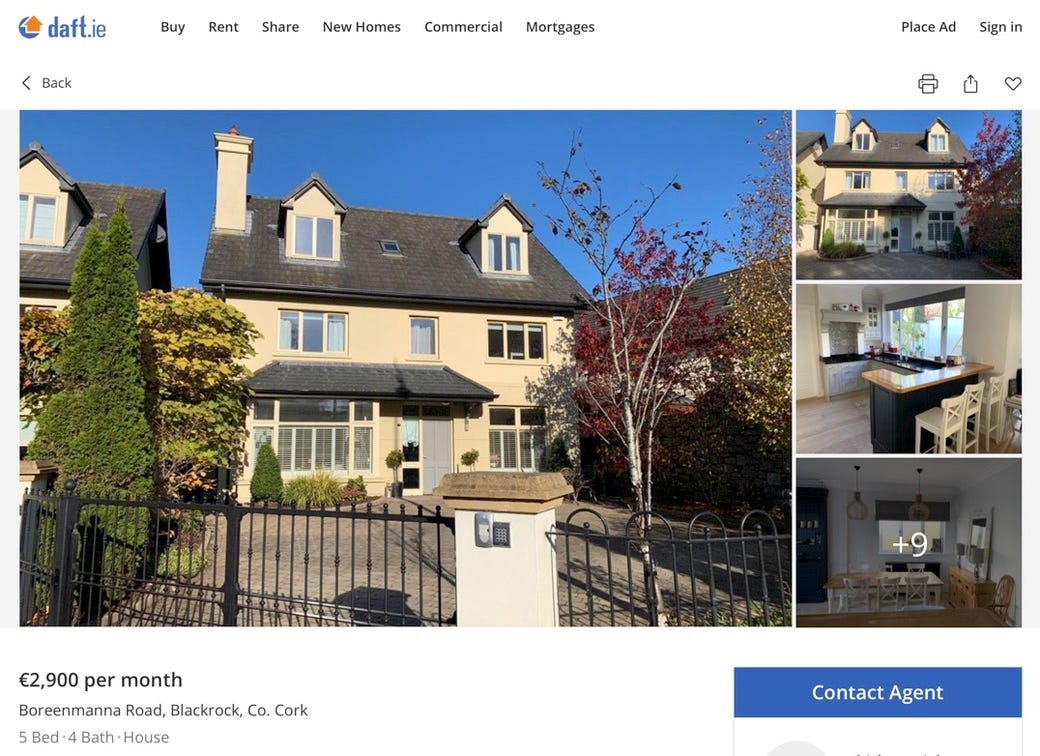

By comparison, long-term letting a similar five-bed to the top earner above would net landlords half of this top-earning short-term let; on Daft, below, a five-bed house in Blackrock would bring in €34,800, and you’d probably have to register on the PRTB and all sorts of other paperwork.

“We don’t know where people are going to get homes.”

At Threshold, Edel is warning of a dire and worsening housing situation, more and more people facing termination notices and ending up in emergency accommodation because there is no fall-back: a plentiful and affordable supply of private rentals can really help in these situations, but there just aren’t any out there.

“I don’t know if it can get much worse,” she says. It’s really worrying for anyone working in the sector at the moment. NGOs are concerned, local authorities are concerned: we just don’t know where people are going to get homes if something isn’t done.”

While the finger can’t solely be pointed at any one factor, and while there are myriad issues including unrealistically low Housing Assistance Payment (HAP) rates, the AirBnB situation “needs attention,” she says.

“The rental properties are there; they just need to be made available to people who need them on a long-term basis.”

“There are regulations in place that aren’t being enforced. Landlords are supposed to apply to the local authority for planning permission if they’re letting their properties through short-term letting platforms for more that 90 days in a year. We would strongly feel that this isn’t being done, and that the local authorities who are supposed to regulate this just don’t have the resources. That’s what’s happening on the ground.”

Enforcing the law

Edel is talking about regulations introduced under the Planning and Development Act 2000, which came into effect on July 1, 2019.

Under the new law, property owners in so-called “rent pressure zones” (RPZs) who short-term let their properties for more than 90 days per year must apply for change-of-use planning permission: they are no longer operating a residential property but a commercial one.

Cork City is an RPZ; of Cork County’s eight Local Electoral Areas (LEAs), Bandon Kinsale, Carrigaline, Cobh, Fermoy, Macroom, Mallow, and Midleton are all RPZs.

I asked Cork City Council and Cork County Council how many change-of-use applications had been made since July 2019, and how many had been granted.

Just 3% of hosts have applied for change of use

51 change-of-use applications have been made over three years, city and county combined. 19 applications have been granted.

In Cork City, where 188 AirBnBs are listed:

4 change of use applications have been made: none in 2019, one in 2020 and 3 in 2021.

None have been granted.

In Cork County, there have been 47 applications and 19 have been granted:

This means that 3% of hosts, from the total of 1,548 current advertised properties, have applied for change-of-use planning permission in line with the law. Certainly, many of them may not have met the requirements and may be letting for under 90 days per year.

But remember that Cork City Council have confirmed to us that they have issued no change-of-use permissions, so none of the top-earning city listings you saw above, where bookings certainly exceed 90 days per year - I checked on their booking calendar on AirBnB - have been granted change-of-use.

Cork City Council say they’ve started “174 investigations into suspected breaches of the short-term letting regulations, and have issued 158 informal warning letters and 30 warning letters.”

So Edel’s assertion that property owners are not self-regulating by voluntarily applying for change-of-use is true, and provable.

“There’s no point introducing something if you don’t have an enforcement team behind it, and that’s what’s happened here,” she says. “Maybe we need a separate body set up to investigate these cases. They have to put the resources in place to ensure the regulations are being enforced.”

Following a Covid-related slump in its finances in 2020, AirBnB bounced back with a vengeance in 2021, with Chesky declaring a “travel rebound unlike any other in history” and the company recording revenue of $5.92 billion according to their financial returns.

This is not the income made by hosts, you understand; this is just what the platform itself made.

There are more than 4 million hosts using the platform worldwide, and with each booking, AirBnB takes a cut.

Corporate tax

Not only that, but they are headquartered in Dublin to take advantage of our low corporate tax rate of 12.5%, but also of our territorial tax system, hugely important to such a multinational company, where you pay absolutely no Irish tax whatsoever on income from other countries.

AirBnB Ireland Unlimited Company paid $9,429,000 in corporate tax in Ireland in 2019 and just $4,536,000 in 2020, according to their financial statements on the CRO website.

Why should the Irish government pay for enforcement resources to counter AirBnB’s voluminous externalities? Edel agrees: she feels the platform itself needs step up and play a role.

“You’d say that a company like that should have measures in place before a property can be rented to ensure that all the local regulations are being complied with,” she says. “With the short-term lets, they should be seeking a certificate from the local authority before they allow anyone to put properties on their platform.”

I sent an email to the listed AirBnB Irish press email address asking to clarify a few points. For two days, nothing happened; I sent another email asking if anyone was monitoring the email address. Eventually I started forwarding the mail to others.

In response to my question asking why AirBnB doesn’t make compliance with local law an actual prerequisite for the use of their platform, this is what I eventually received:

“It’s important that Hosts check the local rules and requirements on hosting before they begin hosting. Our Responsible Hosting in Ireland page provides a starting point for Hosts to learn about hosting regulations and permissions.”

Some AirBnB hosts remain true to the original idea behind the company.

Grace Healy lives near Watergrasshill with her husband and two little girls. She’s a chemical engineer who recently took a career break to stay at home while her children were babies. AirBnB was a handy extra few bob to her family: the digital equivalent of Egg Money, you could say.

Having returned from Amsterdam where they lived for years, Grace and her husband built themselves a big house on land given to them by Grace’s parents.

“I started renting as soon as we moved in,” Grace tells me. “I had a spare room downstairs that was really good for AirBnB because it was down the end of a corridor on its own next to a bathroom, and we’d all be sleeping upstairs, so it’s totally separate.”

From Monday to Friday, the room is occupied by a lodger working for one of the nearby large companies, but at weekends, before Covid, Grace would advertise the room on AirBnB for €35 per night.

It was actually Grace that originally got in contact with me with the idea for this story; she’s part of a Cork homesharer’s club of likeminded non-professional short-term letters in Cork. And she’s bothered by the increasing professionalisation of AirBnB, the emergence of investors as a major player.

Globally, 59% of AirBnB lettings are now “professional accommodation offers,” while just 8% are lettings of a room in a single home, according to a report by Ethical Consumption Review.

Grace is troubled by this; she sends me an impassioned call-to-arms by US documentarian Jared Brock.

Then she tells me something strange. I always presumed that AirBnB was a completely faceless entity, but Grace says a “Host Liaison Officer” got in touch with her, invited her to a WhatsApp group.

“They were wining and dining us,” she says. “We’d meet up every few months and there’d be free food, booze. I never met any of those investor-type hosts, not once. It was all other home-sharers like me. But who knows? Maybe they kept us apart, she could have had a whole separate WhatsApp for them, I don’t know.”

In summer 2019, around the same time that the new planning regulations came in, the host liaison person from AirBnB said she was no longer doing the job, and of course, since then, a lot of Covidy water has gone under the bridge.

I asked AirBnB if they had been operating a host liaison service, and if they cancelled it in summer 2019 and if so why. The response I got was:

“The Kerry & Cork Host Club is run by Hosts, for Hosts, and the volunteer lead shares feedback with a liaison from Airbnb.”

Grace hasn’t been AirBnBing since Covid, but she’d like to get back to it this summer, and she reckons she can charge €50 per night when she goes back, despite her property’s lack of proximity to the city. When she does, the 90-day rule will probably mean she doesn’t have to apply for planning permission.

Nevertheless, she thinks enforcement is essential, that the way AirBnB is currently operating is causing damage to the Irish property market.

“Not for me, but for the good of society, I think it’s really important that it be enforced properly,” she says. “I wouldn’t trust AirBnB to police themselves, would you?”

Kinsale: investors “soaking up available properties”

Grace may not have seen any, but Senator Tim Lombard says that in his electoral area, Bandon Kinsale, investor lettings are absolutely a factor. And that they affect not only the supply of rental properties, but the supply of homes for sale.

“The knock on effect is that because this is so lucrative, investors are coming in and buying up property, so the opportunity to buy is being taken away from people as well,” he says. “I know one particular investor that has eight properties bought up in Kinsale. They are literally occupied for 3-4 months of the year, and then lying idle.”

In the Seanad in mid-March, he made an impassioned plea to the Minister of State for Housing to look into the issue.

“On the morning I gave that contribution to the Seanad, I think there were 50 individual properties listed on AirBnB for the area, and three rental properties on Daft,” Tim tells me.

I check on AirDNA: there are actually 106 active rentals listed for Kinsale today; 68% of these, 73, are entire homes.

“AirBnB properties are literally soaking up the available rental properties in Kinsale, and the unfortunate truth is that lots of these properties are only occupied for three or four months of the year and spend six months plus lying empty. In this housing market, that’s just unacceptable.”

Driving up prices

The presence of investors - the website I’ve been using for the data in this article, AirDNA, is actually designed to help investors to decide on where to purchase short-term lettings - is driving up prices and, Tim says, it’s a problem in some locations more than others.

“It’s an issue in coastal, scenic towns all over Ireland,” he says. “The cost of renting in these towns has gone through the roof, literally 1800 or 1900 for a three bed house or apartment. That’s totally unaffordable for most people.”

An extra windfall from the state

When plans for the €200 energy rebate we’re all going to get in April were being made, Tim was the only one to spot the short-term lettings problem: investors who own multiple properties that have not changed use from residential to commercial will receive the rebate for each property.

“The €200 rebate being given by the State, that’s supposed to help with your energy bill, which is not applicable to commercial properties, all of these residential properties are going to get that,” he says.

That means that some Kinsale investors he knows of, who own between five and eight properties, will be landing themselves a nice little windfall of between €1,000 and €1,600 of taxpayer’s money.

Tim’s warning probably came too late: “I asked the Minister to look into it, and he said he’d go back to the authorities with it. So not only do we not have a proper registration system for these properties, but now the government is going to reward them. It’s bananas.”

To Tim, the flop that has been self-regulation is clear. He says if anything, the rental situation has “deteriorated since 2019.”

There are attempts at further tightening up the regulation of short-term lettings underway; from last February, AirBnB started sharing information with Revenue in attempt to at least ensure that landlords were paying taxes on income earned on the platform.

A short-term lettings registration system overseen by Fáilte Ireland is due to begin in 2023.

Tim says that what comes our way must be far more fit for purpose than attempts to date.

The new registration system “must be robust, they have to take away the self-regulation element, and they must ensure that you must have a planning document to be able to go on the AirBnB website,” he says.

“Scotland brought in really good legislation within the past ten months that makes the platform liable for the properties advertised on their website not having the proper planning documentation.”

“If there’s a need for more bed nights, we can build more of that type of accommodation. We can’t have residential properties used to soak up the commercial, tourism market.”

Who bears the brunt?

42-year-old Siobhán* didn’t want to use her real name to talk to me. Due to debilitating long-term depression, she works part-time and has lived in the same tiny house in Cork city for eight years. Her rent, at just €710, is “incredibly low,” was even low at the time that she first took the house.

Even so, with an income of just €250 per week, and with food prices and other expenses skyrocketing, she feels the pinch; like so many others, the disparity between rent and income means she’s constantly penny-pinching.

“Three weeks of the month I don’t spend anything and then one week I can afford to pay off my bills and do one big shop in a cheap place,” she says. “I can’t ever afford to do things that I’d like to do, like buy local foods or shop in the English Market. I’m getting the factory farmed stuff.”

“It’s basically, get a piece of meat and then things to supplement it: pulses and vegetables. Make a big stew, eat the same damn thing for a week.”

The only catch-net Siobhán has been offered was a recommendation from Intreo to stop working and go on disability benefit. But she says her job is a lifeline in more ways than one: she has an understanding employer and her hours are manageable, and her work stops her from spiralling into depression.

“It’s something I'm living with. I’ve found ways to get joy out of life that are entirely free or very cheap. I do bits of arts and crafts as a physical outlet. I hand-sew stuff from swap groups or charity shops.”

Something even more grinding than the endless worrying about money is the worry about where she will end up; this low rent she’s paying can’t last forever. There is no long-term peace or security in knowing that all it would take is for her landlord to pass away, or to suddenly decide he could cash in on the short-term rentals bonanza, and she would become incredibly vulnerable.

“I rest on my landlord’s good will and good fortune,” she says. “Sometimes a house comes up for rent on the same road as me, and I have a look at it, and it will be double what I’m paying for the same conditions. Anything can happen: life throws up incredibly big surprises sometimes. A slight shift in my landlord’s circumstances, or my work circumstances, will throw everything off kilter and I have no idea what I’ll do. There just isn’t anything I can access if something goes wrong.”

“I have no plans; I can’t make plans in this city. I just live day to day, try to get in time with my family.”