A Cork school built on trust, with no curriculum or teachers

At the Sudbury School in West Cork there are no teachers, there's no homework nor is there a curriculum. Plans are underway to open a similar democratic school in Cork city.

When you think about it the school around the corner hasn’t radically changed in a hundred years or more.

Blackboards might have become green boards and then white boards and thankfully dusters are not launched across classrooms at unsuspecting kids, but teachers still rule, homework is still doled out, tests still matter, most schools insist on uniforms, students are separated by age (and gender in many schools), and uniting all learners is a curriculum - a road map of what students should be learning depending on their age as they collectively move through the education system and enter into adulthood.

I say all learners, but that’s not actually the truth. Students in Ireland who home school are free to learn whatever they want and at anytime of the day they want.

There’s also another category - a small school-going cohort of students spread across three counties - Wicklow, Sligo and Cork - that attend school everyday, but what they learn, and how they learn, and even the environment they learn in is radically different than what is the standard model of education in Ireland and across the world.

At these schools they’ve torn up the rule book and put creativity and consensus to the forefront. Along with the baby and the bath water they’ve thrown out teachers, homework, a class structure and most radically a curriculum.

They are democratic schools, and, as The Atlantic neatly surmised a few years back, “most parents would never consider sending their kids to one. That's because they're run, in great part, by the kids themselves.”

1. The theorist, or what Marcin wants

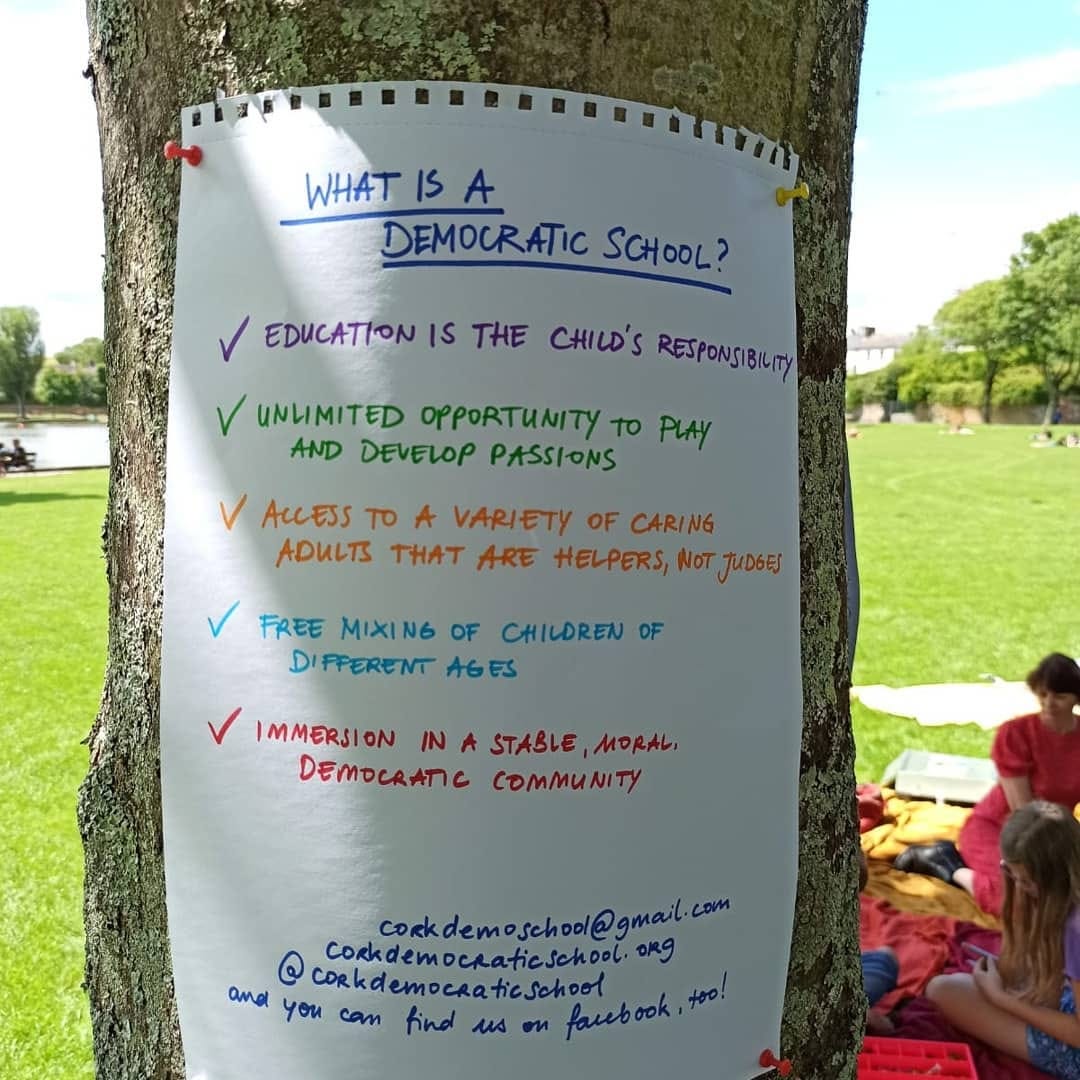

Marcin Szczerbinski, originally from Poland, is an educational psychologist at UCC. His research interests are broad and they include literacy, oral language development and anxiety disorders. Marcin, together with a small core group in Cork city, is one of the backers of the Cork Democratic School. They’re hoping to open their version of a democratic school in Cork in September this year. There’re a lot of obstacles and hurdles ahead, but there’s also a great deal of enthusiasm to do something different.

The first question I asked Marcin about his plan for the new school is if he is a bit mad given the effort and organisation that is required to start any new type of institution, but especially one such as school, and even more so when you’re starting from a radically different position. Such as a school that doesn’t require teachers.

“I would like to say idealistic, but I suppose downright mad is more of an accurate description,” Marcin tells me on our Zoom call.

As to why, Marcin explains that typically it’s parents who are the drivers behind starting a new school or opting to home school.

“I’m childless, I don’t have my own kids, but I am interested in childhood. I’m interested in development, professionally but also personally.”

Marcin is blunt in his assessment of the education system as it currently exists and has existed for a long time: it’s simply “not fit for purpose.”

Marcin first came across the ideas behind democratic education back when he was an undergraduate in Kraków, Poland. He had read Sumerhill by A.S Neill a book about the first ever democratic school in England which celebrated its centenary last year.

The book made an impression on him, but, as he says, he did nothing with it, because at the time “it felt completely impossible”.

However, several years ago he started to see that others in Cork and across Ireland had taken up the ideas of the democratic school and were working on them with the aim to set up democratic schools in Ireland.

For Marcin, a democratic school represents the chance to do “something really good and leave something behind that would be meaningful.”

He’s open also to working at the school if they can get it off the ground, but more on that later.

The group behind the Cork Democratic School was set up in 2017, by a fellow Pole, who has since moved back to Poland, but Marcin and a small band of volunteers are still working on the project to get the school up and running.

Since then (2017) there’s been a long string of people trying to make it happen, mostly but not exclusively a mix of Irish and foreign parents.

Compared to the democratic schools that are up and running in Sligo, Wicklow and West Cork, the plan for the Cork Democratic School is moving slower. The pandemic didn’t help and the core group is transitory, but the belief and will is not lacking Marcin says.

Which brings us back to why?

Education is probably one of the most contentious and controversial subjects that unites us all in agreement and disagreement, and Marcin has clearly set out his stall by saying, as he did at the top of our interview, that the current model and structure of education is not fit for purpose. In explaining why, he also sets out why a democratic school would go some ways to fixing this.

As Marcin explains our contemporary model of education is about 200-300 years old.

“They were developed to serve a set of purposes that may not be obvious. We think that schools are there to educate young people, to equip them with certain skills to deal with life such as the three Rs: reading, writing and arithmetic.”

But, as Marcin outlines, that was only of the motivations for setting up an education system as we understand it today.

“Another big purpose was to indoctrinate people. To turn them into obedient citizens. To convey a certain narrative about our country, our land, serving the powers to be. The education as we offer it today is actually a forced education. There is a set curriculum that neither the student nor the teachers have the freedom to opt out of. You have to follow that curriculum.”

As Marcin explains, the curriculum is the medium: it sets out what we should learn, but also when we should learn and how we should learn it, and this is all reinforced through examination.

“We are conditioned to believe that this is necessary. That unless there was this compulsion, this coercion, people would just not learn anything.”

But there’s no reason to believe that Marcin says, adding that there is plenty of evidence that if young people are given the freedom to do what they want with their time, but also with a supportive community around them that gives them resources to actually learn things that learning would happen. Does happen in fact.

“They (students) do it efficiently and moreover they develop a sense of agency and competence that goes with it which is much harder to develop when you are coerced when others tell you do it.”

Marcin does not mince his words; he uses words such as compulsion and coercion often in describing our current system of schooling, but his thesis goes straight to the heart of an age old school problem about what we learn and why.

Why algebra? Why French? Why Irish? Why at 11:05? Why silently? Why do we all go to the yard now?

Some of this is simply because an organisation as big as a school needs a system and a structure. But as to why Irish or algebra, very often, the most honest answer seems to be because there’s a curriculum and there’s a test, and then there’s more of both.

Zoom out and ask yourself one of the most hotly debated questions of Irish life every year: why the fucking leaving cert? Maybe the bigger question that we don’t ask is why do we learn what we learn at school? And why do we learn it that way? Instead, the answer to the leaving cert conundrum is always - but there has to be something, right?

What we talk about when we talk about democratic schools

According to Marcin there are two main principles of a democratic school:

The first principle

“It is truly democratic. It’s a community of learners, students and staff members, who actually collectively together decide how the school is run. So it’s not the case that the adults have the full and final say in all the rules and regulations and how things are done. It’s actually adults and the children coming together to deliberate to discuss to vote to make the decisions on things such as opening times, what is allowed behaviour and what sanctions do we impose when the rules are broken.”

As Marcin explains what the rules, sanctions and day-to-day structure looks like differ from democratic school to democratic school. In some schools - that is the students and staff members - might decide on a majority vote, “others work on consensus, trying to work on a solution where everyone is reasonably happy.”

The other immediate difference you would notice if you wandered into a democratic school is that it’s mixed ages. Essentially democratic schools combine primary-age students and secondary-age students, so students from five through to their late teens.

“The way we segregate kids by age is very unhealthy and it goes against social development and learning,” Marcin says, adding that “age mixing is a very powerful way of learning.”

As for teachers, well they’re not teachers, or at least they’re not called teachers.

“We would call them staff members,” Marcin says, and their main responsibilities would entail being a mature, sensitive, tuned-in person who wants to maintain the ethos and the direction of the school.

An adult is a person to go to when you have a question or a problem so that you can sound it off against somebody more mature.

“Occasionally an adult would also act in the role of a teacher.”

The second principle:

Self directed learning

“What that means is we don’t have a compulsory curriculum. There are no subjects that students have to study. They are not obliged to attend any lessons, indeed there will be no lesson unless the students request we organise them. And there is no compulsory assessment so students spend the day as they see fit.”

Marcin says that under this rubric it’s likely that younger kids would spend most of their day playing and older kids would probably come up with projects.

Which leads more or less everybody to ask, how would a child learn anything if they weren’t taught by a teacher, or at least someone?

“Much of learning would happen in a very informal, naturalistic, opportunistic kind of way, but as kids get older many of them will opt to focus on certain activities they are interested in and spend time doing them,” Marcin explains.

After interviewing Marcin and reading more about democratic schools I talked to a few people, mostly parents. We have two boys, my wife and I, one is in primary school and the other is on the way to primary school, and I mentioned the ideas behind the democratic school to some of the parents on our daily walk to school.

Most of the parents looked at me with wide-eyed expressions. Pick your analogy, but some that were mentioned were Lord of the Flies and Animal Farm. However, there definitely was curiosity to know more about how exactly a school works if you start from the premise that more or less the existing structure doesn’t work - less we don’t need no education, rather than we need an entirely different form of education, and we’ll figure it out ourselves.

When I called the democratic school an experiment, Marcin pushed back.

“It is actually a tried-and-test model. It’s a rare model. There are not that many democratic schools out there in the world, but it’s going on for a hundred years now.”

One of the most influential democratic schools in existence is the Sudbury Valley School which was founded in 1968 in Framingham, Massachusetts. It’s younger by about 50 years than Summerhill, which was first set up as part of an international school called the Neue Schule in Dresden in 1921. Summerhill moved around a little before A.S. Neill, a Scottish writer and “rebel” moved it to its current location in Suffolk, in England.

Summerhill started with five students and it’s grown considerably, not always smoothly, in the hundred years since. It was also the inspiration and model for Sudbury, the democratic school outside Boston.

The three existing democratic schools in Ireland, as well as the others scattered in countries around the globe all draw from the original Sudbury school as well as all the other schools in the network, but they operate independently.

To the list of things I did not know before writing and researching for this piece is that the Irish constitution gives considerable leeway to anyone who wants to start a school or home school. In its simplest form, parents are responsible for the education of their children, and that gives great scope to any parent or guardian to decide what education they want for their child.

Curriculum are, however, tied indirectly to funding, which is why Ireland’s Sudbury schools are self-funded, fee paying and non-profits. They don’t get money from the Department of Education, but in return there is the freedom to do whatever they want. Tusla do have oversight of child welfare. But funding is a major challenge for democratic schools.

And it’s the funding issue which is the major hurdle for Marcin and the Cork Democratic School. That and finding a building that will become their home, their school. (The accommodation crisis we have in Cork and Ireland is clearly affecting so many different strands of life and industry).

But there’s a group of parents who have managed to start and grow a democratic school in Cork, in West Cork, on a hill overlooking Bantry Bay between Glengarriff and Bantry.

2. The practitioners, or what Jessica, Archer and Tallulah do at their democratic school

Of all the Zoom calls I have been on, Jessica Mason-Little has the best setting so far. To all intents and purposes it looks like a tree house. It’s not, but her husband built it as an office/bedroom/communal space, and it’s the kind of setting that would propel you up an Airbnb ranking. Jessica lives with her family near the West Cork Sudbury School (WCSS) which opened in September 2020, in the first year of the pandemic.

Back then the school house was the Blue Pool hostel in the middle of Glengarriff, but subsequently they’ve moved to Coomhola, which is in walking distance of where Jessica and her family live. There’s more than 20 students enrolled, and the school is growing. They’ve already had one graduation and both Jessica’s kids, Archer and Tallulah, attend WCSS.

Currently there are 22 students enrolled at WCSS, but that’s soon to jump to 25 with a five-year-old student joining after mid-term. Jessica thinks by the end of the school year they could be up to 30 students.

The fact that they’ve opened, and stayed open in a pandemic, completed the move to a new location and are growing “is a testament to how much it’s needed” Jessica says.

Speaking of the pandemic, Jessica thinks that when schools were forced to close to contain the spread of the virus, one of the things that happened is it provided parents with a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to look at the curriculum and what their children are learning. “That’s been opportune for us,” Jessica said, adding that people are more interested in thinking about the education their children are getting.

From conception to opening its doors WCSS got going quiet quickly, which Jessica says is a testament to the core group of parents who got the school up and running in around two years. Not all the core group are parents, nor do they all have kids in the school, but what unites them all is a dedication to build the first democratic school in Cork.

Jessica is at pains to say that they didn’t open in opposition to mainstream schooling, or to criticise it. She says that while main stream schooling works for some, it doesn’t for others.

“But I think for a lot of people they’re questioning what the curriculum aims to achieve - what are we educating for? Because the curriculum was essentially written twenty years ago and we live in a time of accelerated change.”

You could also say that most people don’t give a whole lot of thought to the curriculum too, and as long as it ticks along unnoticed, and we’re not outliers in international league tables then the status quo is fine.

For Jessica, the impetus for setting up Sudbury in West Cork was to create the structure for responsive education and “the fact that you can trust young people to figure it out for themselves as they’re the ones who are going to be figuring out what their lives are going like.”

Which brings us to self directed learning, which Jessica is well placed to talk about as she works at the school in West Cork which her two kids, Tallulah and Archer, both attend.

“It’s trusting that we are innate learners and people will find their passion given the right situation and then they will work out what they want to do with themselves.”

This is one of the other interesting aspects about the direction of learning at democratic schools versus mainstream schools. The way democratic schools are set up, kids are afforded more opportunity to discover or learn what interests and intrigues them from an early age so that they can start off down that path.

Whereas with the main stream curriculum it’s geared more to teach to the test, and the test means points and the points mean you can pass go and pick something you think you might be interested in if you want to move on to third level. Granted, that’s a crude assessment.

It’s still early in the process for Ireland’s three Sudbury schools and there’s much to glean in terms of data and culture as they develop and grow.

When it comes to values, Jessica says that “school meetings and the conflict resolution process is integral to the school as much as any tangible academic learning we do.”

“It’s still early days, and there’s a lot of ground work to do,” she says explaining that the staff members have to remember to be patient too.

There’s a lot of learning too for the students, especially with figuring out how a democratic school works, and that they are literally the ones in charge. That’s a big shift for anyone to deal with, and it sounds like that students and staff members at WCSS are still figuring that out.

When I ask Jessica how the learning process is going at WCSS, she gently points out that “we learn all the time” laughing, but her point is well made. One of the first things you say as a parent to your kids most days after school is “what did you learn today?”

“I think a really important thing to get across is that we have to un-school and de-school ourselves to be able to comprehend that we don’t need to go to school to learn.”

Not all freewheeling

Now in its second year the culture and structure at WCSS is taking shape. There’s a timetable of classes and clubs which includes French lessons, chemistry, science club, creative writing, book club, drama club, cooking, survival club and nature club.

“For the older students they are starting to think, ‘what am I going to do with my life?’” Jessica says.

Jessica is typically in the school for three to four days a week; she taught at a Steiner school in India and her kids went to the same school, so they’re used to sharing a school.

“Funding is a massive, massive challenge as we don’t get any government funding,” she says.

At the moment they are heavily dependent on volunteering by staff members and figuring out how they will be able to pay a living wage is going to be a struggle for them.

Parents pay a “membership due” to send their kids to WCSS. It’s means-tested and the big emphasis is keeping the cost affordable and accessible for all families.

“We don’t want someone to not be able to choose this model of education based on their income,” Jessica says.

At the moment a year at WCSS is 10% of a family’s gross household income (GHI) with the minimum fee of €2,100, based on the average income in West Cork.

There are three core days in every week which is when the students and staff have their conflict resolution process and school meeting and students are expected to be in on those days, but there’s flexibility as to what time students arrive in the morning, with students arriving anytime up to 10:30 a.m. This is also because some students travel quite a distance to get to WCSS. School finishes at 3 p.m. and by 3:30 p.m. most students have filtered out and back to their homes in West Cork. But without homework. Opening later into the evening is also in the plans for WCSS, but that too depends on funding.

How do you teach a child to read and write in democratic school?

When I ask Jessica, how, for example, a five or six-year-old child would learn to read or write in a school without a curriculum or where self directed learning is the curriculum, she points out it’s not like there is a learning vacuum.

They have a library, literacy resources, and “the experience from Subdury schools is that children learn through using the tools of our culture.”

By way of example, Jessica talks about a student who has progressed with their literacy through using Minecraft, the online computer game.

Another student came to a staff member saying they wanted to read a certain set of books, and so the staff member and student dug into them.

“When you choose to learn something you learn it a lot quicker because you have that passion there. I think it’s a combination of the desire to do it, the tools of the culture and the fact that there is that learning environment there and those resources are there (too).”

But what it really comes down to Jessica says is trust. And that’s something that’s hard to teach (and hard to learn).

“We’re trusting the students, the parents are trusting that we’re innate learners given the right environment,” she says.

What Archer thinks

Archer, a teenager, Jessica’s eldest child, starts off by showing me a series of paintings he has created. They look like local scenery but they are landscapes painted from his mind’s eye. Compared to previous schools he has attended he’s been doing a lot more creative things such as painting and board game design.

Jessica explains that he won a competition for board game design held by The Echo in 2021 and a local board game designer volunteers at the school.

When I ask Archer about age mixing at his new school he says that “sometimes it can be a bit difficult but generally I think it can be pretty cool.”

When I ask about the structure of a typical school day, Archer tells me that “there isn’t really any classes unless you want them.” He tells me all this in the way that teenagers politely point out to adults things that are not that complex.

When it comes to the school’s values and how transgressions and sanctions are handled, Archer says, “yeah, that’s TP.”

Jessica takes over.

“This is our conflict resolution process and it stands for Transformative Practice. We also use restorative circles as a way of talking through broader problems.”

TP sounds to me not terribly unlike a court setting with a mediator, the affected person, the invited person and advocates present.

Archer says there’s been quite a few TPs around swearing; age mixing necessitated them.

“(But) some of them have been about students having problems with other students.”

As he doesn’t ever get homework he’s free to work on his own projects at home.

When I ask that question that all adults inevitably do, that is, if he has given any thought to what he wants to be in the future, he answers, “I try not to think about it.”

Archer’s more at ease talking about the school grounds; there’s a lot more outdoor space in their new location and he lists off what’s there: a skate ramp, a big lawn, a basketball court, stables and “sometimes we all do a big game of tag or cops and robbers outside.”

What Tallulah thinks

Tallulah,11, is Archer’s younger sister and she’s currently engaged in writing a book. Before Christmas she finished up a script for a play. She’s also working on an outfit for a ‘Trashion’ show which will be held this April. The fashion will be made from upcycled and recycled outfits.

“I don’t really have that many projects,” she says, before remembering she’s “doing a lot of history.” She wants to build a medieval town.

When I ask Tallulah is she ever feels bored at school she says that happens sometimes. When I ask what she does when she feels bored, she answers that she’ll often wander around thinking of something to do.

As for the age mixing she says she likes hanging out with her friends.

The book she’s writing is a fantasy, but she’s only started writing it.

Mandatory lessons

On paper, democratic schools can sound impossible - how can kids runs a school? But there is structure and there are lessons, they’re just not of the type and format that we experienced in our school settings.

My youngest boy Fionn will be five soon and everyday when he gets home from pre-school he makes a beeline to the sitting room and without exaggeration he can play away for hours with toys such as Lego and GraviTrax and then move on to colouring or cutting things out. He’s playing but he’s learning, and it’s mostly self directed to use the lexicon. Fionn’s hardly unique.

My point being is that we learn as we play, and we learn outside the school. What democratic schools are doing is bringing some of that back inside the school, along with the resources and the tools, but also giving students more agency - a lot more agency- in decision making.

That said, as Jessica explains they do offer a series of essential and mandatory workshops such as the one on internet safety and on consent.

“A big thing on self directed learning is recognising consensual learning and self directing learning skills.”

Jessica recognises that it can be daunting for students finding out that they can learn whatever they want, whenever they want, so these workshops are designed to give them the building blocks to learn, but also to develop the culture of the school.

“I suppose one of the things I’d love to get across is that it’s not just for people who mainstream doesn’t work for. It is an intentional community.”

“It is a lifestyle choice as much as anything. Yes, it can work for kids who mainstream doesn’t work for, but it’s also for people who want to educate their differently.”

What next for the Cork Democratic School?

The core group behind the Cork Democratic School neither have a location nor a building, but they do have a date that they would ideally like to open: this September.

Finding a school building is a big problem, which goes back to funding.

“Ideally we want to be as inclusive as possible and actually have a mixture of people from all walks of life, all socioeconomic backgrounds,” Marcin explains.

But as he points out, unless they find a sponsor, or a big group of sponsors - they’re happy to talk he says, smiling - it will be a fee-paying school, and finding a school building is proving to be a huge difficulty.

“Quite frankly the September deadline is proving to be a tall order.”

The three things that Marcin and his group need to get over the line and to get up and running this year is more members in the core group, a venue for their school and funding.

Marcin said they’ve been looking at vacant and derelict properties in the city, but to no avail.

“If you try to get hold of the owners they don’t want to talk to you or you can’t find who they are, so that’s a really annoying place to be.”

They need to get a foot in the door somewhere Marcin says, if only for a year or two, before they can move on to something bigger, similar to the West Cork school.

As for potential students, Marcin says they have a list of parents who are interested in the school and sending their children there, but how real that interest is is very difficult to ascertain until they have a school building.

Marcin would love to commit to working in the school as a staff member in some capacity, but as to how much he can give he says has to be realistic and weigh up how much of a pay cut he can take and still be able to pay his mortgage.

A democratic school in Cork city could happen this year or it might be next year.

It would be the most radical school in the city and it would be breaking the mould. But as Marcin says they would be building on models that are out there.

“You never know exactly what’s going to happen with a particular combination of staff members and children, but generally it’s a model that’s be tried, tested and described.”

Now they just need to test it in Cork city.

For more information on Cork Democratic School you can visit their site here.

For more information on West Cork Sudbury School you can visit their site here.