943 days on a public waiting list in a Cork hospital...or 21 days to go private

One woman's experience of waiting lists in Cork raises larger questions about Ireland's two-tier system of health provision and how Covid-19 will impact its future.

In 2017, Benchawan Thompson started suffering from bouts of fainting, dizziness, vomiting and episodes of collapse.

The mysterious and worrying symptoms continue to this day. Striking three or even four times per month, they can last days at a time.

“When I get an attack, the symptoms are a pain in my inner ear, with fainting, dizziness, vomiting and not being able to walk,” Benchawan tells me. “Then I get a huge pain on the left side of my head, like a migraine. That can last for six hours or even for days, when I just lie down on my bed and cannot move.”

The impacts on her quality of life are enormous.

An active woman with a love of walking the Irish countryside, Benchawan, originally from Thailand, won’t go on walks alone in areas with poor phone coverage any more.

Not since an episode where she went shopping while her husband, Malcolm, stayed in the car: emerging from her local SuperValu, she fainted and fell to the ground next to her shopping trolley. Luckily, Malcolm was on hand to carry her to the car.

Just this week, the couple decided to take a drive to some potential fishing spots Malcolm was interested in. Arriving home, Benchawan rushed from the car to the bathroom and threw up, the beginning of another bout of symptoms.

“It’s eating up her life,” Malcolm says, frustration and worry audible in his voice.

The couple were living in Skibbereen when Benchawan’s symptoms first emerged. They feared a neurological cause; there were worries of a brain tumour or similar. She visited her West Cork GP, who booked her an MRI scan.

She was put on a public waiting list for a post-scan appointment with an Ear, Nose and Throat specialist at Cork’s South Infirmary Victoria University Hospital (SIVUH) on June 18, 2018. Benchawan has shown me that letter.

She finally got to see her consultant on February 3, 2021.

“Soon Outpatient”

The sequence of events that led to her waiting 943 days, or 135 weeks, for a first appointment with her specialist is a curious one, complicated by the Covid-19 crisis.

Having waited for her appointment throughout 2019, in October 2020, Malcolm contacted SIVUH to ask about the delay and Benchawan received a letter saying that, due to Covid restrictions, her consultant was only seeing patients from his “urgent” list. Benchawan was on his “soon” list.

Malcolm filed a complaint on Benchawan’s behalf; Benchawan is loath to complain in a country where she feels like a guest. She has occasionally had difficulty understanding the medical staff she has seen and gets Malcolm to accompany her to appointments where possible.

Following Malcolm’s complaint, and a letter of response from the hospital, in December 2020, Benchawan was given an appointment to see the consultant this past February.

“John Sampson” goes undercover…

The staggering wait time preyed on Malcolm’s mind.

Of course, consultants triage their patients: if Benchawan’s symptoms, mysterious and debilitating as they are, didn’t put her on the “urgent” list, that was understandable, possibly even vaguely reassuring.

Malcolm knew the same consultant operated a private Ear, Nose and Throat clinic in a North Cork town, and so he called the consultant’s private clinic under a pseudonym, John Sampson, complaining of the same symptoms as his wife.

He was immediately offered an appointment for 21 days later.

“I was able to make an appointment without showing a referral, using a pseudonym, and I was given an appointment 21 days later,” he tells me. “When that date came close, I telephoned again and said I couldn’t make that appointment, and I was able to make another appointment, also 21 days later.”

“It made me quite angry. One accepts that private, paid services will be faster than the public sector. But to have such a differential struck me as inappropriate and totally unacceptable. People’s lives are at stake.”

Benchawan and Malcolm met in Benchawan’s native Thailand 18 years ago, while Malcolm’s life was in transition: he had fallen in love with Thailand while on a round-the-world sailing trip, and had returned en route to Australia when he met Benchawan.

They settled in Skibbereen, where they lived for four and a half years: they moved to Kenmare in the midst of Benchawan’s unfolding hospital appointment saga.

For Benchawan, criticism of an Irish system does not come easy: she doesn’t want to appear ungrateful or rude. But she is appalled by her treatment in SIVUH, and so she wants to speak out.

How does it compare to healthcare in Thailand?

“There, any time I want to see the doctor I can,” she says. “In Thailand, we also have private and public like you have here, and private is very easy to get an appointment. But even if you go public, there might be a long queue, but you will get to see a doctor and you will be able to make an appointment.

“Never would you have to wait for years. This has to be the worst service in the world!”

Still waiting

Benchawan’s single appointment for an SIVUH specialist was inconclusive. The consultant promptly referred her on: she waited eight weeks for an audiology check-up, and is now waiting again for a further specialist ENT appointment.

All South Infirmary consultants operate both a public and private practice, a spokesperson for the hospital confirms to me in an emailed statement. They can’t comment on the specifics of Mrs Thompson’s case.

“We have not yet conducted a full review on the impact of Covid on waiting lists,” the statement reads. “Clinical need will always take preference over a patient’s public or private status.”

Public lists post-Covid, but what about private?

It’s been widely publicised that Covid-19 restrictions and delays have been catastrophic for public outpatient waiting lists.

In February, I reported on the case of Aoileann uí Bheaglaoí, a little girl with Down Syndrome in Co Waterford whose parents have been given a date in 2024 for a routine but vital scan for her.

But I learned of Aoileann’s story while trying to investigate the issues raised in my mind by Benchawan’s story: in our two-tier health system, where cash or private insurance are king, are private patients being left waiting as long as public patients? Has there even been an impact on private waiting times?

Almost 877,000 people are now on public hospital waiting lists, according to the National Treatment Purchase Fund, and the HSE expect 150,000 fewer outpatient appointments to take place in 2021 as the public health service attempts to resume normal service post-Covid.

In a study released earlier this year, the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) found that patients in Ireland’s public heath care system wait far longer for routine operations than other OECD member countries. For hip replacement, knee replacement and cataract surgery we ranked near the bottom of the list on waiting times.

The South Infirmary (SIVUH) had 253 patients waiting for more than 18 months for a consultant Ear, Nose and Throat appointment as of January, while 217 had been waiting between 15 and 18 months, according to data from the National Patients Treatment Fund.

However, the number of patients on private lists and the impact of Covid-19 on waiting times in private sector healthcare is unknown, and almost impossible to discover.

There is no accessible database recording this.

…..So I tried to find out

I contacted the Mater Private in Cork via email, and asked them if their patients could expect delays due to Covid-19 restrictions. They sent me a statement that did not address my question and did not respond to my follow-up query:

"Mater Private Network has been pleased to support the national effort and in particular the local public hospital groups throughout the Covid-19 pandemic. The hospital has and continues to support the public effort through the provision of medical and surgical in-patient and day case capacity, together with related theatre, diagnostics and ancillary support services.

Our Urgent Cardiac Care Service and Emergency Department remain fully operational. Clinics, procedures, and appointments are continuing as planned. Mater Private Network continues to work with both full time private and part time private public consultants."

Private hospitals including Mater Private have agreed to provide surge capacity in the advent of another Covid-19 wave: the details of this contract are not known to me.

I called the Consultant’s Private Clinic at CUH. I was told there was no way of checking whether or not there were additional delays for appointment times; I would need to check with consultants individually. The gentleman on the phone, who did not give his name, told me I was “asking too many questions” when I asked if most of the consultants in the Private Clinic were also operating under public contract in CUH.

So I phoned the secretary of one of the consultant neurologists, with a list of symptoms similar to Benchawan’s. She said, subject to a referral from my GP, that if I were considered a “routine” appointment, I’d be seen privately in September or October. A four-month wait time seems respectable when you consider that the number of public patients waiting more than nine months increased by 41% last year.

But apart from this response, I encountered only surprise that I was even asking, an embarrassed silence.

A two-tier health system that benefits the lives of those that can pay and neglects those that can’t for years on end has become an accepted feature of our society.

Benchawan wants her illness to stop, and to reclaim her life. But for Malcolm, there’s also a matter of principle: he’s English and grew up with the NHS. He finds it difficult to grasp how the Irish system actually works, or rather fails people. He acknowledges they could go private, but he feels this is wrong.

Dual contracts

The vast majority of Irish consultants, who are on staggering salaries (the highest-paid consultant last year was on “basic pay” of €413,747), including Benchawan’s, work on dual contracts which permit them to work both publicly and privately.

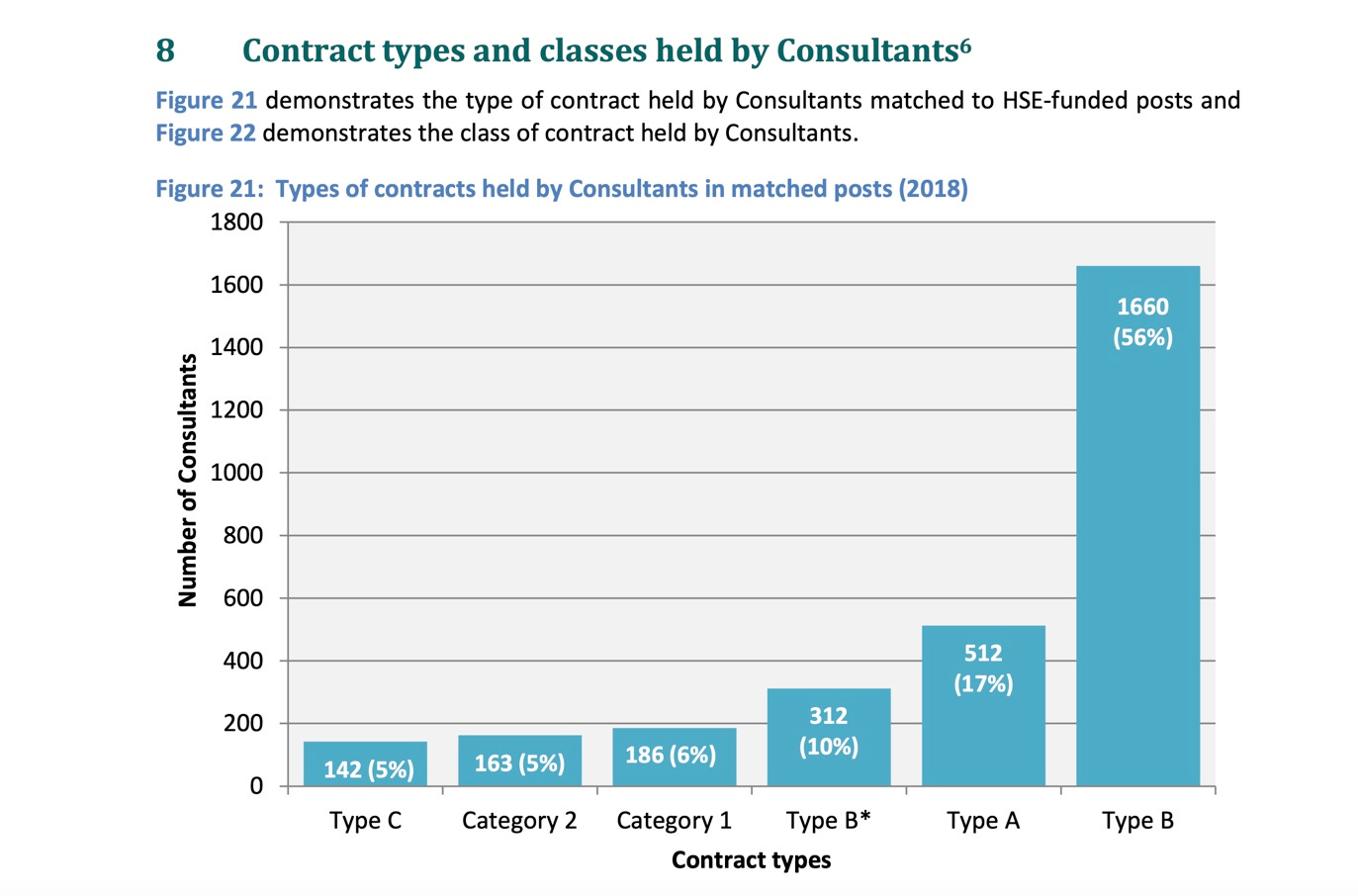

2,463 of Ireland’s consultants, or 83%, are on dual contracts, according to the HSE’s consultant workforce document. 2,700 consultants are on over €100,000 per annum.

For salaries like these, consultants could be asked by government to take an allocation of public patients onto their private lists in light of the post-Covid situation, which will kill some public patients: 400,000 cancer and diabetes screenings were missed last year.

The Covid crisis certainly did no harm to consultants’ pockets: a wage bill to the state of €464.3 million for consultants in 2020 had increased by 11.5% over 2019, including overtime of €11.38 million.

More consultants?

The Irish Hospital Consultants Association (IHCA) frequently claim that the public waiting list travesty can only be solved by hiring more consultants.

“Public hospital and speciality capacity deficits are significant constraints which are the root cause of unacceptable public hospital waiting lists,” they said in a recent press release. Ok, so it’s nothing to do with their members double-jobbing it then.

“There are currently 728 permanent Consultant posts vacant or unfilled on a permanent basis,” they point out. “Ireland also has the lowest number of specialists in the EU on a population basis, at 1.49 per 1,000 population, 41% below the EU average of 2.53.”

I emailed the IHCA when I first heard Benchawan Thompson’s story:

Q: what proportion of IHCA members have both a public and private practise?

A: “We do not have the information required to reply to this question.”

Q: “If a consultant is still able to see his own private patients within three weeks, but has a public patient that has been waiting for two years, how is this a fair situation when it comes to equity of access to healthcare?”

A: “We are not in position to comment on individual cases.”

Negotiations

Two-tier healthcare makes an explicit statement about the value we place on the lives of those fortunate enough to be wealthy and those who are not. For Benchawan and Malcolm Thompson, the fact that Benchawan’s illness is not deemed enough to put her on the “urgent” public list is a small comfort in the face of years of worry and pain with no answers.

When I write these stories, public feedback is usually along the lines of “why don’t they go private?” When I wrote about Aoileann, I got no less than three noble benefactors getting in touch to offer to pay for her MRI scan: well-meaning people who hadn’t grasped that Aoileann’s specialist scan is not available in the private sector.

But the more people that simply turn to private provision in the face of their own need, especially when faced with the farce that is the post-Covid public health service, the more rapidly profits are pushed to private provision.

Today, Sláintecare negotiations get underway. The government will be offering hospital consultants as much as €250,000 per annum to take up public-only contracts.

The outcome of these negotiations remains to be seen. In the meantime, Benchawan Thompson is still waiting for the results of her last round of tests.

If you know of similar stories, I’d love to hear them. And I don’t operate a waiting list.